REGIMENTING TOMATOES

What’s Better: Loosy Goosy or Soldier Straight?

I wonder how much our gardens reflect our personalities? Some gardeners clip their yew bushes “plumb and square;” other gardeners clip or shear away at their plants more haphazardly. Even in the vegetable patch, a temperament may be reflected in the way tomatoes are grown: Do the plants sprawl over the ground with abandon, are they contained within strings woven up and down the row, or are they neatly staked? (Woven tomatoes or those grown in wire cages are more or less sprawling plants, held aloft.)

Whatever your temperament, a good case can be made for staking tomatoes. Tomatoes on a staked plant are larger and ripen earlier than those on a sprawling plant. Good air circulation around leaves and fruits of upright plants lessens disease problems. And fruits held high above the ground also are free from dirt and slug bites. You’ll harvest less fruit from each staked plant, but since staking makes best use of the third dimension, up, staked plants can be set as close as eighteen inches apart. So staking gives the best yields per square foot — especially important in small gardens.

Flavor Picks

Tomato varieties suitable for staking are so-called “indeterminate” types, which form fruit clusters at intervals along their ever-elongating stems. “Determinate” varieties, in contrast, bearsfruits at the ends of their branches, so if a plant was pruned for staking would be reduced to a single short stem capped by a single cluster of fruits. Seed catalogues and packets usually indicate which varieties are suitable for staking.

Determinate varieties are bushy plants that need little regimenting. They also ripen their fruits within a shorter window of time.

So what’s not to like about determinate varieties? Flavor! With fewer leaves per fruit than indeterminate varieties, flavor suffers. That concentrated ripening period also can stress the plants, making them more prone to disease.

As you might guess, I grow only indeterminate varieties of tomatoes. Flavor is my main criterion in selecting a variety to grow.

Staking

When choosing a suitable stake for staking (indeterminate, of course) tomato plants, don’t be misled by the puniness of tomato transplants. A tomato stake needs to be be six to eight feet long and metal or at least one by two inches thick if made of wood. I use EMT (electrical metallic tubing) conduit, 5/8 inch diameter and 10 feet long, cut down to 7 feet. It’s easy to pound into the ground (okay, I’ll admit that here on the floodplain there are no rocks), easy to remove, and reusable for years and years.

Most books and other sources of information suggest “planting” your stake along with your tomato plant to avoid root damage later on. Not true. My established tomato plants never bat an eyelash (figuratively speaking) as I pound in metal stakes only a couple of inches from their stems. And there’s a good reason to wait until the plants are well-established; by then, chance of cold damage is reliably history. Early planted stakes would interfere with my trying to throw a protective blanket over a row of staked tomatoes should cold threaten.

With the base of a stake set a couple of inches from a plant and a 3 foot length of iron pipe, capped at one end and slid over the conduit’s free end, the stake pounds in easily with repeated lifting and forcefully lowering.

Indeterminate tomatoes are vines, but not vines that can climb by themselves. So they need to be tied to their stakes. Material for ties should be strong enough to hold the plants the whole season, and bulky enough so as not to cut into plants’ stems. Coarse twine or cotton rags, torn into strips, are good materials. I use sisal binder twine.

The usual recommendation, when tying, is to first tie a knot around the stake tightly enough to prevent downward slipping, then use the free ends of the rag strip or twine to tie a loose loop around the plant’s stem. False! With every foot or so of growth, I tie a single loop loosely around stem and stake above a node; the string can’t slip down lower than the node.

Pruning

Now for the pruning: Confine each plant to a single stem by removing all suckers, ideally before any are an inch long. A sucker is a shoot that grows from a bud originating at the juncture of a leaf and the main stem.

Go over your plants at least weekly, using your fingers to snap off each side shoot. (Cutting the shoots with a knife or pruning shear may transmit disease between plants as a blade touches cut surfaces.) Occasionally step back and refocus your eyes on the plant as a whole; I find that I sometimes overlook a sucker that has snuck up with two feet of growth I missed as I focussed on still small shoots just appearing from buds.

One final bit of pruning that some gardeners practice is to pinch out the growing tip of the plant when the stem reaches the top of the stake, then continue to remove any new leaves or flowers that form. This is a little chancy, since the effect depends on the maturity of a plant’s leaves and fruits. At worst, you reduce yield to a few clusters of fruit. But at best, your tomatoes are even earlier and larger. It may be worth a try on a couple of plants.

How do your tomatoes grow, up or sprawling. A case can be made for “up.” But you need the right variety, stake, and method of pruning.

They’re a little finicky to sprout, so I collected seeds from one of my plants and planted them in a seed flat, where I could watch and nurture them individually, then transplant them to individual pots. Here it is, three years later, and later this summer, delicate pink flowers will hover like small butterflies above each of the ten fat tubers.

They’re a little finicky to sprout, so I collected seeds from one of my plants and planted them in a seed flat, where I could watch and nurture them individually, then transplant them to individual pots. Here it is, three years later, and later this summer, delicate pink flowers will hover like small butterflies above each of the ten fat tubers.

The above listing gives minimum, not optimum, temperatures for germination. Optimum temperatures might be even thirty degrees higher than the minimums, as in the case of celery which germinates quickest at seventy degrees. Waiting for the optimum temperature isn’t advisable, though. To delay sowing until the soil temperature reached the optimum temperature for pea germination (seventy-five degrees) would result in a midsummer harvest, when hot, dry weather turns peas coarse in taste and texture.

The above listing gives minimum, not optimum, temperatures for germination. Optimum temperatures might be even thirty degrees higher than the minimums, as in the case of celery which germinates quickest at seventy degrees. Waiting for the optimum temperature isn’t advisable, though. To delay sowing until the soil temperature reached the optimum temperature for pea germination (seventy-five degrees) would result in a midsummer harvest, when hot, dry weather turns peas coarse in taste and texture.

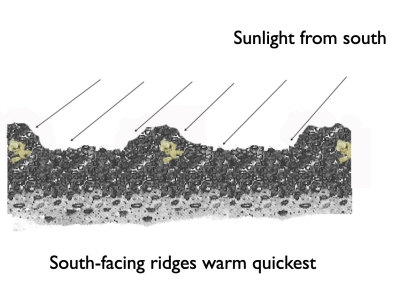

(For the same reason, here in the Northern Hemisphere, south-facing slopes are warmer than north-facing slopes. North-facing slopes ideal for planting peaches and apricots to delay their flowers to when there’s less possibility of a later spring frost snuffing them out.)

(For the same reason, here in the Northern Hemisphere, south-facing slopes are warmer than north-facing slopes. North-facing slopes ideal for planting peaches and apricots to delay their flowers to when there’s less possibility of a later spring frost snuffing them out.)

Borrow a taste from a neighbor’s asparagus bed, or from a wild clump along a fencerow, and you’re likely to want some growing outside your own back door. Minutes-old asparagus has a very different flavor and texture (both much better) than any asparagus that reaches the markets. The time to plant is now.

Borrow a taste from a neighbor’s asparagus bed, or from a wild clump along a fencerow, and you’re likely to want some growing outside your own back door. Minutes-old asparagus has a very different flavor and texture (both much better) than any asparagus that reaches the markets. The time to plant is now. Planting asparagus beyond the confines of the vegetable garden works out well because the lacy, green foliage stands as a backdrop for perennial flowers. Or, it can soften the line of a wall or fence.

Planting asparagus beyond the confines of the vegetable garden works out well because the lacy, green foliage stands as a backdrop for perennial flowers. Or, it can soften the line of a wall or fence.

Then, when the spring sun warms the soil, energy stored in the roots fuels growth of the spears. As the spears grow higher and higher, feathery green branches unfold. Photosynthesis within these green branches pumps energy to the root system, energy that keeps the roots alive through the winter and fuels early growth of spears the following spring, thus completing the plant’s annual cycle. (The true leaves of asparagus, which are the small scales on the stems, are much reduced in size and function; the green stems take on most of the job of photosynthesis for this plant.)

Then, when the spring sun warms the soil, energy stored in the roots fuels growth of the spears. As the spears grow higher and higher, feathery green branches unfold. Photosynthesis within these green branches pumps energy to the root system, energy that keeps the roots alive through the winter and fuels early growth of spears the following spring, thus completing the plant’s annual cycle. (The true leaves of asparagus, which are the small scales on the stems, are much reduced in size and function; the green stems take on most of the job of photosynthesis for this plant.) Remember, the plants do need some time to nourish their roots in preparation for winter. Following the last harvest, all new green stems are left untouched until their summer job is over, as they turn brown in the fall.

Remember, the plants do need some time to nourish their roots in preparation for winter. Following the last harvest, all new green stems are left untouched until their summer job is over, as they turn brown in the fall.

The main challenge with this plant is clearing and separating the almond-sized tubers from soil and small stones.

The main challenge with this plant is clearing and separating the almond-sized tubers from soil and small stones.

They’re often billed as the “bread tree” because in contrast to other nuts, which are high in fats and protein, chestnuts are high in starch. Obviously, you’re not going to be eating home-grown chestnut stuffing this year, or next, or the next; it takes awhile for a chestnut tree to start bearing. Not that long though. I’ve had plants grown from seed begin to bear within six years, and a grafted tree from a nursery should bear even sooner than that.

They’re often billed as the “bread tree” because in contrast to other nuts, which are high in fats and protein, chestnuts are high in starch. Obviously, you’re not going to be eating home-grown chestnut stuffing this year, or next, or the next; it takes awhile for a chestnut tree to start bearing. Not that long though. I’ve had plants grown from seed begin to bear within six years, and a grafted tree from a nursery should bear even sooner than that.

Native Americans harvested and ate nu nu, and this was one of the foods crucial in helping the Pilgrims survive their first winters in Massachusetts.

Native Americans harvested and ate nu nu, and this was one of the foods crucial in helping the Pilgrims survive their first winters in Massachusetts.