ABOUT PEPPERS

Better Late than Never

Cold has finally gotten the better of my pepper plants. Two below freezing nights a month ago started their demise, and two more during the last few nights finally finished them off for the season. Not the fruits, though, plenty of which are piled and spread out in trays and baskets in the kitchen.

Outdoors, fruits weathered the below freezing temperatures well. They’ve been shielded from the full brunt of cold by their canopies of increasingly floppy leaves. Also, fruits of plants are higher in sugars than are the leaves. Thinking back to high school chemistry, I recall that any solute, such as sugar, lowers the freezing point of the solution. So pepper fruit cells can tolerate more cold than pepper leaves.

Even with the plants dead outside, the pepper season isn’t over here. The season has been greatly extended by harvesting and bringing indoors sound, green peppers showing any bit of red — or yellow if that’s the pepper’s ripe color. Sitting in trays and baskets in the kitchen, these mostly green peppers have been ripening, depending on when they were harvested and how long they’ve sat, to fully red or yellow color, when they are most flavorful (to me).

For some reason, perhaps the heat interfering with pollination, peppers started ripening later in the season than usual. The present and the past few week’s abundance of them makes up for the late start.

Thank You C2H4

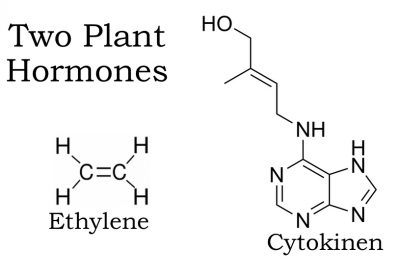

For the peppers’ morphing from green to red or yellow, I have to thank, in large part, a simple gas made up of just two atoms of carbon and four atoms of hydrogen. It’s ethylene, a plant hormone. Most plant and animal hormones are much more complex molecules.

Ethylene is produced naturally in ripening fruits, and its very presence — even at concentrations as low as 0.001 percent — stimulates further ripening. The ethylene given off by ripe apples can be used to hurry along ripening of tomatoes, by placing an apple in a closed bag with the tomatoes.

Banana, apple, tomato, and avocado are among so-called climacteric fruits, which undergo a burst of respiration and ethylene production as ripening begins. These fruits, if picked sufficiently mature, can ripen following harvest.

Peppers, along with “figs, strawberries, and raspberries are examples of non- climacteric fruits, whose ripening proceeds more calmly. Non-climacteric fruits will not ripen after they’ve been harvested. They might soften and sweeten as complex carbohydrates break down into simple sugars, but such changes might be more indicative of incipient rot rather than ripening or flavor enhancement.” Or so they say. And, I admit, I’ve said; that quote is from my book The Ever Curious Gardener. (The rest of the section about ethylene in my book is correct.) They and I were wrong.

So, I’ve learned two things. First of all, pepper do ripen well after harvest, not only to a bright color but also to a delicious flavor. And second, further reading has revealed that hot peppers, but not sweet peppers, are, in fact, climacteric fruits.

What about semi-hot peppers? Or non-hot hot peppers? (Read on.)

Hot and Not

I did also grow some semi-hot peppers this season. Roulette is a variety billed as resembling “a traditional habanero pepper in every way (fruit shape, size and color, and plant type) with one exception – No Heat!” Roulette had an interesting flavor that I both liked and didn’t like (mostly liked), and occasional ones did have some heat to them, but that might have been due to their proximity to . . .

Red Ember is billed as an early ripening hot pepper with “just enough pungency for interest.” It definitely caught my attention when I bit into one! Call me a wimp, but I thought it was fiery hot.

Peppers, Red Ember and Roulette

In my previously mentioned book, The Ever Curious Gardener, I also explored flavor in fruits and vegetables and, briefly, hotness in hot peppers. “Studies have been done with peppers, focusing specifically on their hotness, which, to muddy the waters, stems from not one, but from a whole group of compounds, capsaicinoids, mostly capsaicin and dihydrocapsain. Hotness in peppers was found to depend on the variety, the environment, and the interaction between variety and environment, with smaller fruited peppers less influenced by vagaries of the environment. Usually, but not always, a pepper will have more bite if plants are grown with warmer nights, with colder days, with just a little too much or too little water, or with fertility imbalances; increased elevation elicits the fiercest bite. Basically, with any sort of stress.”

Uncommonly hot temperatures this summer may very well have turned up the heat in Red Ember and put some heat in Roulette.

mpost? Interested in details about how to make gourmet compost? This is a reminder that on Wednesday, September 23, 2020 from 7-8:30pm EST, I’ll be hosting a webinar about composting. For more information and registration, go to

mpost? Interested in details about how to make gourmet compost? This is a reminder that on Wednesday, September 23, 2020 from 7-8:30pm EST, I’ll be hosting a webinar about composting. For more information and registration, go to

The wall supports the bed of them planted along with lingonberries, mountain laurels, and rhododendrons. These plants are grouped together because they are in the Heath Family, Ericaceae, all of which demand similar and rather unique soil conditions. That is, high acidity (pH 4 to 5.5), consistent moisture, good aeration, low fertility, and an abundance of soil organic matter. The small blueberries send me back to many summers ago in Maine when a very young me hiked in the White Mountains and picked these berries from plants growing amongst sun-drenched boulders. Care needed: mulching in autumn, and cutting a portion of the planting to the ground with a hedge trimmer every second or third winter.

The wall supports the bed of them planted along with lingonberries, mountain laurels, and rhododendrons. These plants are grouped together because they are in the Heath Family, Ericaceae, all of which demand similar and rather unique soil conditions. That is, high acidity (pH 4 to 5.5), consistent moisture, good aeration, low fertility, and an abundance of soil organic matter. The small blueberries send me back to many summers ago in Maine when a very young me hiked in the White Mountains and picked these berries from plants growing amongst sun-drenched boulders. Care needed: mulching in autumn, and cutting a portion of the planting to the ground with a hedge trimmer every second or third winter.

This variety, carrying genes of some species of Asian raspberry, has a sweet, delicate flavor unlike any other variety. Physically, the berries are similarly sweet and delicate, a pale, pinkish yellow. Their fragility makes them a poor commercial fruit so you won’t see them for sale. Grow them.

This variety, carrying genes of some species of Asian raspberry, has a sweet, delicate flavor unlike any other variety. Physically, the berries are similarly sweet and delicate, a pale, pinkish yellow. Their fragility makes them a poor commercial fruit so you won’t see them for sale. Grow them.

The compost will nourish the asparagus . . . and the weeds, most of which I hope will be sufficiently young or weakened to not push up through the compost and the wood chips to light.

The compost will nourish the asparagus . . . and the weeds, most of which I hope will be sufficiently young or weakened to not push up through the compost and the wood chips to light.

I grow only Sweet Mama and Waltham winter squashes. The first variety is botanically Cucumbita maxima and the second is C. moschata; the two species do not cross-pollinate.

I grow only Sweet Mama and Waltham winter squashes. The first variety is botanically Cucumbita maxima and the second is C. moschata; the two species do not cross-pollinate. Distance between varieties can prevent cross-pollination. So can fine mesh bags. I plan to use small organza bags normally sold for wedding favors.

Distance between varieties can prevent cross-pollination. So can fine mesh bags. I plan to use small organza bags normally sold for wedding favors.

The bulbs take root, grow, bow, and deposit the bulbs another few inches away, so, unfettered, the plant spreads by “walking” around the garden. I stopped growing it because the flavor was too sharp for me.

The bulbs take root, grow, bow, and deposit the bulbs another few inches away, so, unfettered, the plant spreads by “walking” around the garden. I stopped growing it because the flavor was too sharp for me.