MOUSEY THREATS AND SOLUTIONS

Food and Lodging

Mice have been seeking bed and board, all to the detriment of us gardeners. Already their devilish deeds are evident in the gnawed bark at the base of a poor little apple tree that I planted in spring.

There are a few kinds of mice, and the meadow vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus) — also known as the meadow mouse or field mouse — is most at home in tall grass. There, this rodent finds food and a place to nest and scamper about shielded from the hungry eyes of hawks, owls, weasels, skunks, and other predators.

Unfortunately, from fall to spring, meadow voles like to supplement their usual diet of grasses and herbs with the bark of trees. My trees! Your trees!

Meadow-vole, Cephas, Attribution-Share-Alike-4.0-International.jpg

Inhospitality

The first line of defense against meadow voles, then, is to create an environment inhospitable to them. Read more

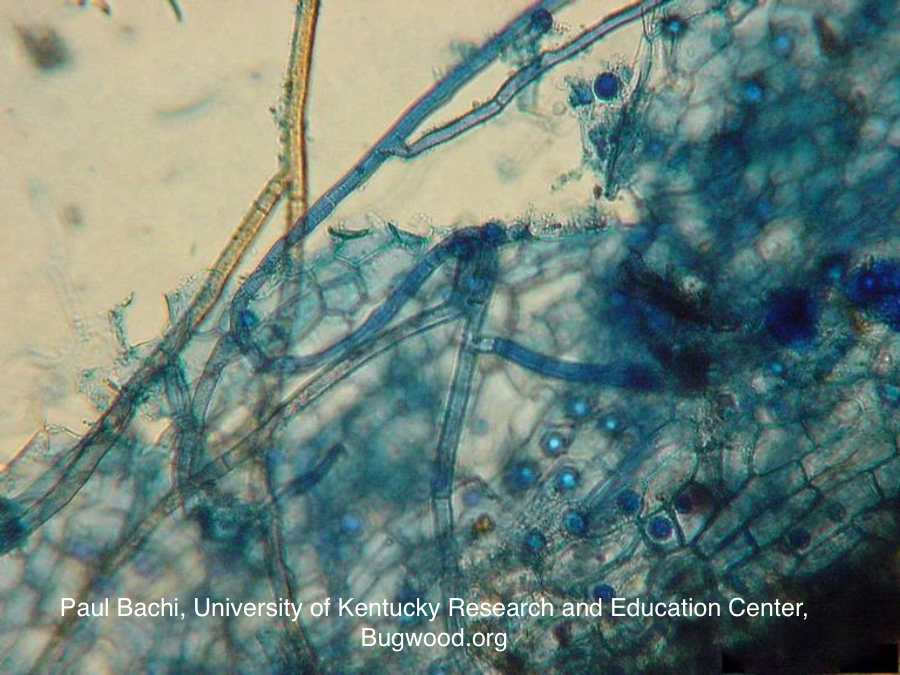

Even though powdery mildew is pretty reliable in showing up each season on certain plants — this is important! — the disease doesn’t necessarily spread from one kind of susceptible plant to the next. Many different fungi are responsible for the disease we collectively call powdery mildew, and each of these fungi have specific plant hosts. Thus, the fungus that causes powdery mildew on lilac (the fungus is Microsphaera alni) cannot cause powdery mildew on rose (caused by the fungus Sphaerotheca pannosa).

Even though powdery mildew is pretty reliable in showing up each season on certain plants — this is important! — the disease doesn’t necessarily spread from one kind of susceptible plant to the next. Many different fungi are responsible for the disease we collectively call powdery mildew, and each of these fungi have specific plant hosts. Thus, the fungus that causes powdery mildew on lilac (the fungus is Microsphaera alni) cannot cause powdery mildew on rose (caused by the fungus Sphaerotheca pannosa).