CREATURES LARGE AND SMALL

Identity Crisis?

For the past couple of months, I’m not so sure that my duck knows that she’s a duck. She and another female duck once shared a drake, and they all lived together in their own “duckingham palace.”

Sometime after the other female and the drake were taken by a predator, probably a fox or coyote, I thought our remaining female might enjoy some company at night. So I coaxed her to take up nightly residence with our three chickens — a rooster and two hens — who have their own house (“chickingham palace?,” actually more palatial than duckingham palace).

Not only has Ms. Duck moved in with the chickens at night but she also wanders around with the flock by day. Her special companion is the rooster, especially since the two chicken hens decided to spend much of their days sitting on imaginary eggs. Neither hen has laid a real egg for over a month. So the female duck and the rooster stroll together each day, gobbling up insects, weed seeds, and some vegetation, except, of course, within the fenced confines of the vegetable gardens. I’ve even caught them in flagrante delicto.

The duck, being a duck, enjoys water. Her idea of a pond is the 3-foot-diameter children’s sandbox repurposed with water that we’ve provided for her bathing pleasure. During the bath, the rooster stands nearby, watching and seemingly trying to figure out what’s going on with his water-loving belle.

Beetles and Vespids

This season has seen both an abundance and a lack of some other, smaller creatures here on the farmden. In July, I saw a few Japanese beetles and braced for an onslaught, ready to repel them with a spray of neem extract or kaolin clay if things got ugly. Although I heard about the beetles descending in hordes on some other gardens near and far, I’ve hardly seen any all summer since then.

This beetle-less trend has been going on here for a few years. I’m not sure exactly why. Japanese beetles do have some natural predators and diseases, including beneficial nematodes. Whatever’s helping out, I’m thankful that they’re doing their job.

Making up for a lack of Japanese beetles has been an abundance of yellowjackets, reflecting, perhaps, good weather conditions, for them, in spring. In contrast to honeybees, yellowjacket colonies do not overwinter; only the queens do. But the bigger the colony this summer, the more young queens develop to fly off and find winter quarters to build up colonies next summer. These insects start out the season feasting on high protein foods but have now shifted to sweets.

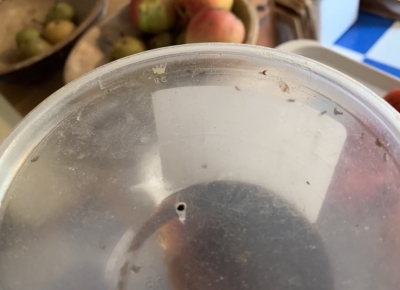

European hornets are also in abundance, with their large size looking more frightening than the yellowjackets but, in fact, not nearly so aggressive. They do have a bigger appetite for fruits, though, often hollowing out whole apples to leave nothing but most of the skin, intact.

Yellowjackets and European hornets have made me more cautious when berry-picking. The insects are capable of breaking through thin skins so are actually robbing a significant part of the late summer raspberries. A close eye is needed to avoid harvesting an angry yellowjacket along with a berry. Early in the morning, they are especially grumpy when wakened from their resident berry.

Yellowjackets and European hornets are also a problem on compost piles in progress. Fresh additions to the pile, especially sweet ones such as melon rinds, quickly need covering with a layer of hay or manure. This hides the food and gets it composting.

Although yellow jackets are beneficial in the garden for eating plant pests, their present habits mostly outweigh the good, for me, at least. (I’m allergic to their stings.) I destroy any nests I happen upon with torch or insecticide. Insecticides with mint as their active ingredients are very effective.

A Bag for Protection

Grapes have tougher skins than raspberries, skins that can resist yellowjackets. That is, until a bird takes a peck or a couple of diseased berries split open.

In anticipation of problems with yellowjackets, European hornets, honeybees, birds, insects, and diseases, earlier this summer we enclosed 100 bunches of grapes in white delicatessen bags. Not that all unbagged grapes get attacked. But the bagged bunches can be left hanging the longest to develop fullest flavor. Most of the time, we tear open the bags to reveal perfect bunches of grapes.

For the first time, this year, I enclosed some grape bunches in organza bags. (Organza is a fine mesh fabric often used to enclose such items as wedding favors.) These bags were working really well until the European hornets got hungry enough to poke feeding holes in them. This ruined some of the berries and allowed access to fruit flies.

The first grapes of the season, Somerset Seedless and Glenora, started ripening towards the end of August. The first of these varieties is one of many bred by the late Wisconsin dairy farmer cum grape breeder Elmer Swenson. The fruits of his labors literally run the gamut from varieties, such as Edelweiss, having strong, foxy flavor (the characteristic flavor component of Concord grapes and many American-type grapes) to those with mild, fruity flavor reminiscent of European-type grapes. Somerset Seedless is more toward the latter end of the spectrum and, of course, it’s seedless. Swenson red and Briana, which are ripe as you read this, are more in the middle of the spectrum.

The first grapes of the season, Somerset Seedless and Glenora, started ripening towards the end of August. The first of these varieties is one of many bred by the late Wisconsin dairy farmer cum grape breeder Elmer Swenson. The fruits of his labors literally run the gamut from varieties, such as Edelweiss, having strong, foxy flavor (the characteristic flavor component of Concord grapes and many American-type grapes) to those with mild, fruity flavor reminiscent of European-type grapes. Somerset Seedless is more toward the latter end of the spectrum and, of course, it’s seedless. Swenson red and Briana, which are ripe as you read this, are more in the middle of the spectrum.

As you might guess from Elmer’s location, all the varieties that he bred are very cold-hardy.

Thanks, Elmer.

Perhaps the label made the bags even less attractive to grape-hungry birds and insects; at any rate, they worked very well, usually yielding almost 100 late harvest, delectably sweet and flavorful, perfect bunches of bagged grapes each year.

Perhaps the label made the bags even less attractive to grape-hungry birds and insects; at any rate, they worked very well, usually yielding almost 100 late harvest, delectably sweet and flavorful, perfect bunches of bagged grapes each year. Organza is an open weave fabric often made from synthetic fiber. Small organza bags typically enclose wedding favors; the bags come in many sizes. Organza bags have the advantage over paper bags of letting in more light. A mere pull of the two drawstrings makes bagging the fruit very easy; paper bags involve cutting, folding, and stapling. Organza bags also re-usable. (The bags also work well with apples which, in contrast to grapes, require sunlight to color up.)

Organza is an open weave fabric often made from synthetic fiber. Small organza bags typically enclose wedding favors; the bags come in many sizes. Organza bags have the advantage over paper bags of letting in more light. A mere pull of the two drawstrings makes bagging the fruit very easy; paper bags involve cutting, folding, and stapling. Organza bags also re-usable. (The bags also work well with apples which, in contrast to grapes, require sunlight to color up.)

Yes, I know the plant is pretty, provides early nectar for pollinators, and is edible. But its out of place in my vegetable beds. The tarp does it in.

Yes, I know the plant is pretty, provides early nectar for pollinators, and is edible. But its out of place in my vegetable beds. The tarp does it in.

A close eye is needed on cabbage and its kin because one day there’ll be no damage and next time you look, leaves are riddled with holes and poop.

A close eye is needed on cabbage and its kin because one day there’ll be no damage and next time you look, leaves are riddled with holes and poop.