Inside and Outside

Houseplant Envy

I wonder why my houseplants look so unattractive, at least compared to some other people’s houseplants. I was recently awed by the lushness and beauty of a friend’s orchid cactii, begonias, and ferns. I also grow orchid cactii and ferns, so what’s with mine?

Perhaps the difference is that other’s houseplants have a cozy, overgrown look. Mine don’t. Most of my houseplants get repotted and pruned, as needed, for best growth. Every year, every two years at most, they get tipped out of their pots, their roots hacked back, then put back into their pots with new potting soil packed around their roots. In anticipation of lush growth, stems also get pruned to keep the plants from growing topheavy.

Rather than being scattered willy-nilly throughout the house or clustered cozily in corners, as in friends’ homes, my houseplants get carefully sited. For best growth, plants, especially flowering and fruiting plants, need abundant light, something that’s at a premium this time of year. So my houseplants huddle near south-facing windows like baby chicks near a heat lamp. And then in summer, when light, even indoors, becomes more adequate and the plants could move a bit back from the windows, I move them all outside so that summer sunlight, rain, and breezes can really get them growing.

What can I say? I’m too focussed on good growth, and that’s not necessarily what makes for the prettiest houseplant. It’s the difference between a lush plant packed into and overflowing its pot, along with elbow to elbow neighbors, versus one that’s had its soil refreshed frequently, its stems thinned out and pruned back, always with younger stems raring to grow. I can’t help myself.

Choice of houseplants also comes into play. Houseplants that are prettiest for the longest period of time — and need less light — are those valued for the shapes and colors of their leaves. I gravitate to houseplants with fragrant flowers or fruits, or — even better — fragrant flowers and fruits. Pumping out lots of flowers and, especially, fruits demands much more energy from a plant than just growing leaves. And that energy comes from sunlight and young leaves that are efficient at working with that light. Hence the repotting and clustering near sunny windows of my houseplants.

Perhaps it’s also a matter of the “grass is greener,” to me, in someone else’s house. I’ll start looking at my houseplants more with the eye of an appreciative visitor.

Winter Cold: The Good and the Bad

The temperature was 9° and we were on our way to go cross-country skiing when a friend asked if there was any benefit to the cold weather. Plantwise, that is. We knew the weather was good for skiing. Interesting question, and the answer is “yes.”

The first benefit that comes to mind is the effect of cold on diseases, certain diseases, at least. The cold kills them. Peach leaf curl, for instance, is a disease that overwinters in peach buds, resulting in leaves that unfold thickened and twisted and eventually yellow and fall so fruiting and growth suffer. Except in cold winters. My winters are usually cold enough so this disease is rarely a problem.

A number of summers ago late blight disease of tomato went on the rampage here and throughout the Northeast. That disease can’t spend the winter this far north because it’s too cold. In that past summer and some other summers, the disease hitchhikes north on infected plants brought here or, when winds and humidity are just right, hopscotches along north from one infected field to the next.

Insect pests that overwinter in the soil are more damaged the colder the soil gets, and bare soil gets colder than mulched soil, all of which highlights the balancing acts necessary in gardening.

Pests notwithstanding, bare ground isn’t good for plants and soil. Plant roots are more likely to be damaged by the increased exposure and, especially evergreens, are more apt to dry out because more water will evaporate from bare ground and because roots have a hard time drinking in water from frozen ground. Bare ground is also subject to erosion and nitrogen loss.

On the other side of the coin, bare soil goes through more cycles of freezing and thawing, which breaks up and moves around soil particles, in effect tilling the soil. Back to the previous side of the coin, that freezing and thawing can move soil around enough to heave plants, especially small or newly rooted plants, up and out of the ground.

So, I like cold weather for my plants. But I mulch heavily. And I especially like it, as do the plants — and, admittedly, some pests — when there’s an additional blanket of snow over the ground. It also makes for good skiing.

Usually the plant is pest-free but a few years ago something, perhaps a fungus, perhaps an insect, started attacking it, leaving the flesh dry and crumbly. I have yet to identify the culprit so that appropriate action can be taken.

Usually the plant is pest-free but a few years ago something, perhaps a fungus, perhaps an insect, started attacking it, leaving the flesh dry and crumbly. I have yet to identify the culprit so that appropriate action can be taken.

Weeds have been removed from the paths and the beds, and spent plants have been cleared away. What remains of crops is a bed with some tall stalks of kale that were planted back in spring. Yet another bed is home to various varieties of lettuce interplanted with endive, all of which went in as transplants after an early crop of green beans had been cleared and the bed was weeded, then covered with an inch depth of compost. Also still lush green is a bed previously home to edamame, which was subsequently weeded, composted, and then seeded with turnips and winter radishes back in August.

Weeds have been removed from the paths and the beds, and spent plants have been cleared away. What remains of crops is a bed with some tall stalks of kale that were planted back in spring. Yet another bed is home to various varieties of lettuce interplanted with endive, all of which went in as transplants after an early crop of green beans had been cleared and the bed was weeded, then covered with an inch depth of compost. Also still lush green is a bed previously home to edamame, which was subsequently weeded, composted, and then seeded with turnips and winter radishes back in August.

Below ground, oat roots pull up nutrients that rain and snow might otherwise leach away into the groundwater.

Below ground, oat roots pull up nutrients that rain and snow might otherwise leach away into the groundwater.

As I write, in September, the variety Elliot is still bearing ripe berries.

As I write, in September, the variety Elliot is still bearing ripe berries.

Last fall I thoroughly cleaned up diseased plants, even planted some celeriac this year in the greenhouse. Failure occurred both outdoors and in the greenhouse, although lots of rain and heat could have helped (the fungi or bacteria, not me).

Last fall I thoroughly cleaned up diseased plants, even planted some celeriac this year in the greenhouse. Failure occurred both outdoors and in the greenhouse, although lots of rain and heat could have helped (the fungi or bacteria, not me). Left to its own devices, a fig can grow into a tangled mess. In part, that’s because fig trees can’t decide if they want to be small trees, with single or a few trunks, or large shrubs, with sprouts and side branches popping out all over the place.

Left to its own devices, a fig can grow into a tangled mess. In part, that’s because fig trees can’t decide if they want to be small trees, with single or a few trunks, or large shrubs, with sprouts and side branches popping out all over the place.

All that despite my attempts at control by going over plants with a toothbrush dipped in alcohol, oil sprays, and sticky barriers to keep ants, which “farm” these pests, from climbing up the trunks.

All that despite my attempts at control by going over plants with a toothbrush dipped in alcohol, oil sprays, and sticky barriers to keep ants, which “farm” these pests, from climbing up the trunks. Those seeds will drop and germinate in the cooler temperature a few weeks hence. But I need cilantro now.

Those seeds will drop and germinate in the cooler temperature a few weeks hence. But I need cilantro now.

So I started the water sprays again, which have the potential problem of creating so much humidity and moisture that ripening figs rot. On the other hand, it might set back the scale, perhaps by knocking off ants, who “farm” scale. I also ordered a new predator, one for scale, Aphytis melinus.

So I started the water sprays again, which have the potential problem of creating so much humidity and moisture that ripening figs rot. On the other hand, it might set back the scale, perhaps by knocking off ants, who “farm” scale. I also ordered a new predator, one for scale, Aphytis melinus. Birds also eat fruit for their juiciness, and the past weeks and weeks of abundant rainfall probably satisfied some of that need. The only other year I had plenty of mulberries — much more than this year — was a few years ago when 17-year cicadas descended upon here. All summer I awoke to their grating cacophony, but did feast on mulberries as birds feasted on the cicadas.

Birds also eat fruit for their juiciness, and the past weeks and weeks of abundant rainfall probably satisfied some of that need. The only other year I had plenty of mulberries — much more than this year — was a few years ago when 17-year cicadas descended upon here. All summer I awoke to their grating cacophony, but did feast on mulberries as birds feasted on the cicadas.

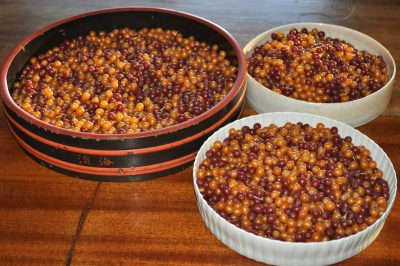

The plants were autumn olives (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrubs whose fine qualities I’m reluctant to mention for fear of eliciting scorn from you knowledgable readers.

The plants were autumn olives (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrubs whose fine qualities I’m reluctant to mention for fear of eliciting scorn from you knowledgable readers. Those fruits are very puckery until a little after they turn red, but then become quite delicious, and healthful.

Those fruits are very puckery until a little after they turn red, but then become quite delicious, and healthful.

I’ve huddled all these pots together against the north wall of my house but soon have to mound leaves or wood chips up to their rims to provide further cold protection.

I’ve huddled all these pots together against the north wall of my house but soon have to mound leaves or wood chips up to their rims to provide further cold protection. After the handles have been wiped down, 10 minutes later, they’ll be in good condition for at least another year.

After the handles have been wiped down, 10 minutes later, they’ll be in good condition for at least another year. The pear trees, close to the house, don’t get bothered. The problem with such cages is that it’s a hassle to weed or prune within the cage — both very important for young trees. Two metal stakes, each a 5 feet length of EMT electrical conduit, woven into part of fencing on opposite sides allows me to slide the fence up and down to get inside a cage to work. These trees, which are replacing my very dwarf apple trees, are semi-dwarfs which can fend for themselves once they get above 5 feet. Then I’ll remove the cages.

The pear trees, close to the house, don’t get bothered. The problem with such cages is that it’s a hassle to weed or prune within the cage — both very important for young trees. Two metal stakes, each a 5 feet length of EMT electrical conduit, woven into part of fencing on opposite sides allows me to slide the fence up and down to get inside a cage to work. These trees, which are replacing my very dwarf apple trees, are semi-dwarfs which can fend for themselves once they get above 5 feet. Then I’ll remove the cages.