FOR THAT UNWELCOME MEDITERRANEAN LOOK

One Name for Many Diseases

The powdery white coating I notice on leaves of my peony and lilac plants gives them a very Mediterranean look. Not attractive, though, at least to me, because that’s a sign of a disease, appropriately called powdery mildew. If I look around the garden, the disease is probably showing itself, or soon to do so, on a wide variety of plants, including phlox, zinnia, squash, gooseberry, and many more. (This blog post is excerpted from the chapter about plant stresses in my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden.)  Even though powdery mildew is pretty reliable in showing up each season on certain plants — this is important! — the disease doesn’t necessarily spread from one kind of susceptible plant to the next. Many different fungi are responsible for the disease we collectively call powdery mildew, and each of these fungi have specific plant hosts. Thus, the fungus that causes powdery mildew on lilac (the fungus is Microsphaera alni) cannot cause powdery mildew on rose (caused by the fungus Sphaerotheca pannosa).

Even though powdery mildew is pretty reliable in showing up each season on certain plants — this is important! — the disease doesn’t necessarily spread from one kind of susceptible plant to the next. Many different fungi are responsible for the disease we collectively call powdery mildew, and each of these fungi have specific plant hosts. Thus, the fungus that causes powdery mildew on lilac (the fungus is Microsphaera alni) cannot cause powdery mildew on rose (caused by the fungus Sphaerotheca pannosa).

Even though powdery mildew on cucumbers and phlox are caused by the same genus and species of fungus, Erysiphe cichoracearum, the race of this fungus that attacks cucumber is incapable of attacking phlox; and vice versa.

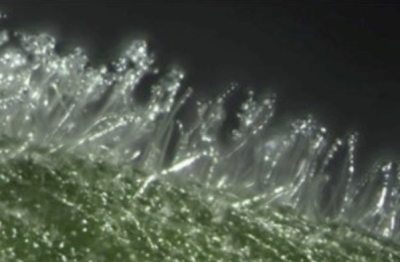

The name powdery mildew describes the appearance of the disease, typically beginning as white patches on leaves and under suitable conditions eventually coating whole leaves.

Early stage powdery mildew

The fungal threads spread primarily on the outside of the plant and periodically send “pegs” down into the plant with which to extract food. As the disease progresses, leaves become deformed, infected fruits turn leathery, and flower buds fail to open.

I’ve had it. You’ve probably had it. What can we do about it? Read on.

Multi-pronged Attack

In contrast to most other plant diseases, powdery mildew thrives in dry weather. Rainfall actually washes the spores off plants. The spores do need a little moisture to induce them to germinate and infect a plant, but dew left on leaves when cool nights follow hot days is sufficient. Here we get a little dry weather and a little rainy weather throughout every season, just enough for at least some powdery mildew, not like out West, where summers of cloudless skies result in cool, dewy nights and plenty of powdery mildew.

Magnified powdery mildew on leaf

Pruning can help keep powdery mildew in check. Less overcrowding of branches lets more sunlight and breezes dry leaves quickly to limit the amount of disease, others in addition to powdery mildew.

Giving herbaceous plants sufficient elbow room has the same effect of drying leaves faster for less powdery mildew disease. Cutting all stems of these plants down to the ground at the end of the season removes some of the inoculum for next year’s infection, although it won’t prevent spores from blowing in from your neighbors’ gardens, and further.

Good nutrition also helps. Plants are more resistant to attack if they are adequately nourished with potassium and not overly lush from too much nitrogen.

Some plants are inherently more resistant to powdery mildew than are others. The apple varieties Cortland, Baldwin, and Jonathan are particularly susceptible to powdery mildew, as are grapes of European, but not American, origin.  Miss Lingard (Wedding Phlox) and Eva Cullum are amongst the phlox varieties resistant to powdery mildew.

Miss Lingard (Wedding Phlox) and Eva Cullum are amongst the phlox varieties resistant to powdery mildew.

Last year a friend gave me some red bee balm (Monarda) that’s resistant to the disease. . Resistant perhaps, but not immune. A web search will turn up a number of varieties, a few of them red-flowered, that are powdery mildew disease resistant.

If All Else Fails

If site selection, pruning, and fertilization fail to thwart powdery mildew — and, sad to say, they often do fail — sprays can come to the rescue. Before spraying, weigh the benefits of spraying against the costs in terms of time and trouble. Powdery mildew on plants such as lilac and zinnia usually occur late enough in the season so that the effect is purely cosmetic, doing the plants little harm. I generally let it be or find some resistant variety. But you can do more . . .

The simplest, least toxic and most convenient spray would be water. Rain it on plants to wash off the spores, doing so on a dry, sunny day so that leaves dry quickly.

If the decision is made to spray, just any fungicide won’t do. Some, even some nonorganic, chemical sprays, can’t do anything to stop the disease. One organic sprays that is (allegedly) effective against powdery mildew is baking soda. I never found it effective. If you want to give it a try, mix four teaspoons of baking soda in a gallon of water, adding a little soybean oil to make it stick better to leaves. Baking soda is sodium bicarbonate; commercial formulations, containing instead potassium bicarbonate (‘Kaligreen’ and ‘Greencure’, for example), are less likely to damage plants.

Gooseberry powdery mildew, despite baking soda spray

Another organic spray is a commercial formulation — named Serenade — of the beneficial bacterium Bacillus subtilis. This one also didn’t work for me but, as is often said for lots of situations, “Your experience may be different.”

I have some faith (with some basis) on two other relatively benign sprays, both organic, for controlling powdery mildew: sulfur and horticultural oil. The latter is sometimes sold as “summer spray” oil; also suitable would be one of the plant-based oils such as neem oil or jojoba oil.

Certain plants could be damaged by sulfur, and either sulfur or oil damages most plants if sprayed in very hot weather, when temperatures are above 90°F. Never spray both materials within 2 weeks of each other.

Powdery mildew is no newcomer to gardens. It is perhaps the mildew mentioned in the biblical passage “I smote you with blight and mildew; I laid waste your gardens and vineyards . . . ” (Amos 4:9).

Similarly, sulfur — traditionally known as brimstone — has a long tradition of use as a fungicide. As far back as 800 B.C., in Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey, he writes that Odysseus, following the bloodbath after killing all suitors to his wife Penelope, calls out to his “dear nurse” Eurycleia: “Old woman, bring sulphur here to purify the house. And bring me fire so I can purge the hall.” Burning sulfur was, and still is sometimes, used for fumigation.

Phlox and zucchini here. Every. D**ned. Year.

We’ve found spraying horsetail plant tea somewhat effective – stumbled upon that solution online at a site whose frequent visitors (we are not!) grow a certain recreational often not legal plant indoors, where fungal diseases are even more of a hazard in the environments the growers create. Their thinking is that the high silica content in horsetail plant is what makes it effective.

Would love to see some actual trials of this approach, but we’ve not been rigorous in doing side-by-side comparisons here.

Thanks again for another very informative post.

Horsetail definitely has potential ofr, as you wrote, its silica content. A silica based fungicide has even been patented: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1515&context=patents

Interesting, thanks! I’m uncertain as to just what “nanoformulation” entails, and would steer away from such a product until I could be certain it did not make use of nano plastics.

Fortunately, horsetail grows abundantly in the nearby woods, and making the tea is simple enough.

Thanks again.

I’ve got several Monarda hanging around here (Greene County, upstate NY) and by far the most smitten with powdery mildew is, unfortunately, the beautiful and ever-enthusiastic fistulosa that pops up everywhere. I have a couple Monarda varieties I have carried with me and planted wherever I’ve lived over the years that I originally purchased in CA. Their leaves are much fuzzier and these plants seem much less prone. Not sure if the pubescence changes how water ‘acts’ and lingers (or not) on the leaves, or if the hairs interfere with a suitable surface area on which the spores thrive? Hm. Anyways, thank you for the article, nice to know I’m not alone with my powdery mildew up here on this hill.