PERENNIAL VEGGIES AND A DEAD AVOCADO

King Henry Was, And Is, Good

The good king has gone to seed. Good King Henry, that is. A plant. But no matter about that going to seed. The leaves still taste good, steamed or boiled just like spinach.

The taste similarity with spinach isn’t surprising because both plants are in the same botanical family, the Chenopodiaceae, or, more recently, the Amaranthaceae. Spinach and Good King Henry didn’t change families; their family was just taken in by, and made into a subfamily of, the Amaranthaceae.

Whatever its name — and it’s also paraded under such common names as poor man’s asparagus and Lincolnshire spinach — Good King Henry is a vegetable that’s been eaten for hundreds of years, except hardly ever nowadays. While spinach, beet, and some of its other kin have been improved by breeding and selection over the years, Good King Henry was neglected.

But the Good King, besides having good flavor, has a few things going for it lacking in spinach. It’s a perennial plant, it’s edible all season long, and it has no pests problems worth mentioning. This Mediterranean native made its way to my garden over 20 years ago, from seed I purchased and sowed. I haven’t had to replant it since then.

Which brings me to one possible downside of Good King Henry: It keeps trying to spread beyond the far corner of the garden where I originally planted it. Every spring I yank out errant plants, and eat them.

One of my favorite things about Good King Henry is its species name, bonus-henricus, making its whole botanical name Chenopodium bonus-henricus.

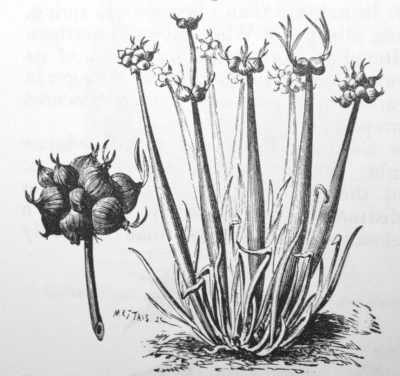

Another Perennial Oldie

Another perennial vegetable that I’ve enjoyed this spring is seakale (Crambe maritima), a relative of cabbage, broccoli, and kale. This also is an old-timey vegetable, one whose popularity peaked in the 18th century; Thomas Jefferson was a fan.

The origin of the name may trace to the leaves (kale-like) being pickled to bring aboard ships (the “sea” part of the name) to prevent scurvy.

Seakale, though perennial, does not spread. I started my plants from seed a few years ago, which is tricky only because the seeds have a low germination percentage. I’ve seen a few seedlings pop up a foot or so from the mother plant, which I welcome as an easy way to multiply my holdings.

Seakale tastes very good either cooked or raw, something like a mild cabbage with a refreshing touch of bitterness. Either way, blanching is needed to make it tasty, and that entails nothing more than covering it for a couple weeks or so, more or less depending on the weather (more warmth, less time), to keep out light and make the shoots more mild and tender. I invert a clay flowerpot over the whole plant, with a stone or saucer over the drainage hole to keep light from wending its way in. Like asparagus, new leaves eventually need to be set free to bask in the sun to fuel the roots for the next year’s early shoots.

One more plus for seakale is that the plant is a beauty, so much so that it’s sometimes planted as an ornamental. The wavy, pale bluish green leaves have a silvery pallor reminiscent of the British seascape to which they are native. Later in the season, a seafoam of white blossoms rises from the whorl of leaves.

I Give Up

Now for an about face, from European plants enjoying cool weather and sometimes dry conditions, to a tropical American plant. Awhile back I wrote about my efforts to grow avocados here in New York’s Hudson Valley. Not on a large scale; just one or two plants from which I could harvest a few fruits of some special variety.

I grew two plants from seeds I saved from locally purchased avocado fruits, and grafted onto those seedlings the stems of two varieties a gardening buddy sent up from Florida. Ungrafted, the seedling plants would bear fruit of unknown quality, if they bore at all. Grafted plants would give me improved, named varieties that would bear quickly.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

I failed. Only one graft took, yet two varieties are needed for fruiting. As expected, the grafted stem on the successfully grafted plant flowered within a year of grafting. For days I tried to get the pollen from the male to pollinate the female parts of the flower — to no avail. And then, for some reason, the grafted stem started to darken and turn black, and died back.

I give up on trying to grow an indoor-outdoor avocado plant — for fruit — in a pot.