A Tree Takes a Plane Ride

I managed to pack lightly for a journey, many years ago, to the West Coast, toting along only an extra pair of pants, a couple of shirts, and a few other essentials. But on the return trip, how could I resist carrying back such bits of California as orange-flavored olive oil and chestnut-fig preserves? The most obvious bit of California that I brought back was a potted bay laurel plant (Lauris nobilis), its single stem poking out of my small backpack and brushing fragrant leaves against the faces of my fellow travelers.

Bay, with its subtropical pals, rosemary and citrus

Not only did the bay laurel bring a bit of California to my home, but also traditions dating back thousands of years from its native home along the Mediterranean coast. Ancient Romans crowned victors with wreaths of laurel and bestowed berried branches upon doctors passing their final examinations. (The word “baccalaureate” comes from bacca laureus, Latin for “laurel berry”.) Bay laurel was sacred to Apollo, so was planted near temples.

Although bay laurel can grow fifty feet tall, my plan was to develop this plant into a small tree with a single, upright trunk capped by a pompom of leaves. The Mediterranean climate is characterized by hot, dry summers, and cool, moist winters. Since the plant is hardy only to about fifteen degrees Fahrenheit, I had to grow it in a pot. The plant is allegedly a rich feeder, but my plants grows fine in my homemade potting mix which contains a healthy portion of compost and — for some extra oomph — some soybean meal.

The potted tree decorates the house in winter, the terrace in summer, and provides fresh bay leaves for soups and other dishes year-round.

A Winter Home

It is in winter that my plant realizes just how far it is from its Mediterranean home. Winters in its home lands are typically cool and moist. Winters inside a northern home are typically warm and dry. Since cool rooms are moister than warm rooms in winter, the cooler the room the better, preferably below fifty degrees. My bay laurel has wintered well either in sunny window in a cool room or near a bright window in my basement, where temperatures are very cool. The warmer the temperatures, the more light bay laurel needs.

The other challenge to my bay tree has been scale insects. They sit along leaves and stems under their protective shell as they suck sap from the plant.  Actually, it’s more of a challenge to me because the plant tolerates scale reasonably well. Once moved outdoors in spring, the plant soon recovers from the attack and its resident scale population, either from the changed environment or from predators, subsides.

Actually, it’s more of a challenge to me because the plant tolerates scale reasonably well. Once moved outdoors in spring, the plant soon recovers from the attack and its resident scale population, either from the changed environment or from predators, subsides.

The problem for me is that the insects exude a sticky honeydew that drips onto furniture and the floor. A sooty black fungus then feeds on the honeydew.

This summer I’ve taken a more active role in thwarting scale by spraying the plant weekly with horticultural oil, which is nontoxic to humans and soon evaporates.

Lollipops

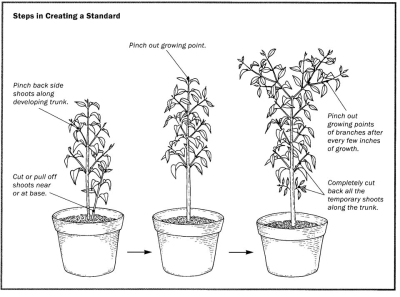

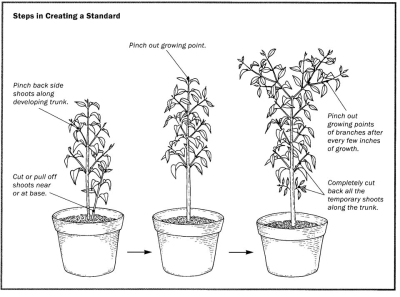

Bay laurel can be trained to any number of shapes such as a pyramid, cone, or globe, with these shapes beginning at ground level or capping a long or short piece of trunk.

Right from the get go, I chose to grow my tree as a “standard.” “Standard” has many meanings both in and out of horticulture, so let’s first get straight which kind of “standard” we are dealing with: Here, I mean a naturally bushy, small plant trained to have a clear, upright stem capped by a mop of leaves. A miniature tree.  In the world of gardening, people are divided over how they feel about “standards.” Some gardeners love them, others will have nothing to do with them.

In the world of gardening, people are divided over how they feel about “standards.” Some gardeners love them, others will have nothing to do with them.

(A “standard” apple tree is one grafted to a rootstock that does not confer any dwarfing.)

For training my lollipop-shaped bay tree, I allowed only a single stem to grow straight upward, and then pinched off any side shoots that developed. When the trunk reached three feet in height, I pinched out the tip to cause branches to form high on the stem. I kept this up, pinching branches and then their branches, to cause further branching, thus forming a dense head. (I devote a whole chapter to standards in my book The Pruning Book.)

Training a standard (rosemary, in this case)

Or, in an illustration (from The Pruning Book):

Ongoing care of the tree entails pruning and pinching to keep the mop head to size, and root pruning and repotting the plant every couple of years or so. The time to do any trimming to keep a plant in shape is mostly just as soon as the new shoots mature and stop growing in early summer.

A few years ago, I decided that my tree was too tall and unwieldy; I wanted a shorter standard. Easy: I just lopped the whole plant to the ground and started again. With an established root system fueling new growth, I was able to develop the new lollipop quickly.

All this pinching and pruning yields fresh bay leaves, which find their way into the kitchen. The fresh leaf has a strong flavor, and one cookbook suggests (and I now confirm this) using one leaf for a dish to serve four people. The aroma of the fresh leaf is more than just strong; it actually has a different quality than that of the dried leaf. The fresh aroma is almost oily, to me somewhat reminiscent of olive oil — how California-ish!

I finally gave up on Chester because winter cold would snuff out many of its canes down to ground level. If I remember correctly, surviving canes bore fruit that was too late in the season to ripen fully or in sufficient quantity.

I finally gave up on Chester because winter cold would snuff out many of its canes down to ground level. If I remember correctly, surviving canes bore fruit that was too late in the season to ripen fully or in sufficient quantity.

Actually, it’s more of a challenge to me because the plant tolerates scale reasonably well. Once moved outdoors in spring, the plant soon recovers from the attack and its resident scale population, either from the changed environment or from predators, subsides.

Actually, it’s more of a challenge to me because the plant tolerates scale reasonably well. Once moved outdoors in spring, the plant soon recovers from the attack and its resident scale population, either from the changed environment or from predators, subsides. In the world of gardening, people are divided over how they feel about “standards.” Some gardeners love them, others will have nothing to do with them.

In the world of gardening, people are divided over how they feel about “standards.” Some gardeners love them, others will have nothing to do with them.

Branch bending to regulate growth and fruiting is especially evident with an espalier, which is a tree grown in an orderly, usually two dimensional form. Lurking behind the many forms, fanciful and otherwise, for espaliers is an appreciation for their effects on growth and fruiting.

Branch bending to regulate growth and fruiting is especially evident with an espalier, which is a tree grown in an orderly, usually two dimensional form. Lurking behind the many forms, fanciful and otherwise, for espaliers is an appreciation for their effects on growth and fruiting.

Another way to hold this wide angle is to press one end of a toothpick into the shoot and the other into the trunk, just enough to keep the toothpick in place.

Another way to hold this wide angle is to press one end of a toothpick into the shoot and the other into the trunk, just enough to keep the toothpick in place. Tying a string around a branch, and then to a weight on the ground or to the tree’s trunk is another way to pull a branch down. Or, you can affix a weight right to the branch. For instance, glue a clothespin to a rock, then clip it to the branch.

Tying a string around a branch, and then to a weight on the ground or to the tree’s trunk is another way to pull a branch down. Or, you can affix a weight right to the branch. For instance, glue a clothespin to a rock, then clip it to the branch.