TO EACH HIS OR HER OWN

Full Disclosure: I Like It

You either like the look of a pollarded tree, or you don’t. A tree pruned by this technique surely doesn’t have a natural look. In winter, the pollarded tree is a clubbed head capping a clear trunk, or clubbed heads each capping a few short, thick side branches atop a clear trunk. In summer, a mass of vigorous shoots wildly burst forth from that club-like head or heads.

Pollarded catalpa

Pollarding has both an aesthetic and a practical side. Because the exuberance of each season’s new growth is well-contained, all of it originating from just one or a few points, pollarding is a way to lend a formal appearance to a tree.

Pollarding is also an easy way to control the size of an otherwise large-growing tree. Once the tree is shaped, pruning requires no special skill and a minimum of climbing or moving a ladder among the limbs. Even a disinterested high school kid could be hired and instructed to merely lop every stem all the way back to the “club,” its origin.

Pollarding seems to have isolated but diverse appeal. You find such trees lining streets of San Francisco and some European cities, as well as standing sentinel in front of homes in rural Delaware. Years ago, I periodically drove Route 222 near Reading, Pennsylvania; rows of pollarded trees done up with varying degrees of skill lined, perhaps still line, the roadway.

Example of poor pollard, functionally & aesthetically

Another poor example of pollarding

But Why, and What?

Pollarding originated out of need, centuries ago in Europe, as a means of harvesting firewood without killing a tree. Regularly cutting a tree to the ground — coppicing — accomplishes the same thing on those trees that readily regrow following such severe pruning. The problem with coppicing was that the succulent, young sprouts that grew following each harvest were prey to grazing animals. On a pollarded tree, stems are cut back to a point well above the ground, where new sprouts are safe from grazing animals.

Pollard in winter

Fast-growing deciduous trees that don’t mind drastic, annual pruning are ideal candidates for pollarding. Among such trees are tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), catalpa (Catalpa bignonioides), horse chestnut (Aesculus Hippocastanum), linden (Tilia spp.), London plane tree (Platanus X acerifolia), princess tree (Paulownia tomentosa), sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), willow (Salix spp.), and chestnut (Castanea spp.).

Multi-headed sycamore pollard

The vigorous, new shoots that emerge after cutting back some of these trees offer their own special effects, in addition to the pollarded look itself. Vigorous sprouts, especially if not originating too high in a tree, often grow like juvenile trees, and one characteristic of juvenile growth is extra-large leaves. Witness the enormous leaves — each a two feet or more across — on vigorous sprouts of princess tree.

Other trees have young stems with brightly colored bark. The way to create a flaming red head on a

Chermesina white willow

(Salix alba) is to stub all stems back to their origin each year, inducing growth of vigorous, young, red-barked sprouts.

Pollarding is also a neat, literally, way to get harvest of willow stems for basketry. Coppicing could also supply stems but would not be as neat, would require you to reach all the way to the ground for harvest, and, because less wood is left after pruning, results in less vigorous regrowth.

How To

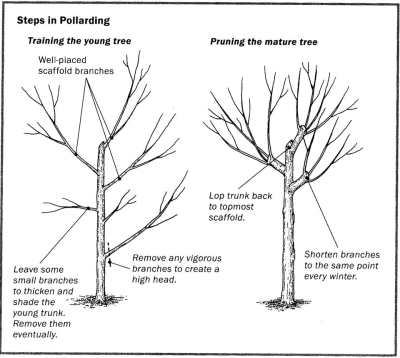

No special techniques are needed when developing a young tree to a pollarded form except to give it a high head, to sit above at least a few feet of clear trunk. This high head is for appearance’s sake only. As the young tree grows, don’t let any side branches develop unchecked along the lower length of trunk. Side branches there do help to thicken the trunk and shield it from sunlight, though, so do not remove them completely. Keep low side branches pinched back so that they grow no more than a foot in a season, then cut them off completely after a few years.

For the plant that will be pollarded to a trunk with a single clubbed head, cut back the trunk in winter to the height that you want for that head.

If your pollarded tree is to be the type having stubby side limbs growing off atop a length of clear trunk, start selecting those side limbs as soon as the trunk is long enough. Choose as permanent side limbs those that are spirally arranged around the trunk, spaced six to eighteen inches apart vertically, and radiating out out at wide angles.

Once side limbs are chosen, don’t allow the trunk to keep growing upward. Before it grows too thick or too far out of reach, lop it back to just above the topmost side limb.

When side limbs are a few feet long, shorten them to a point between two and five feet from the trunk. You also may want to remove any side branches growing off these limbs.

The eventual size of the tree determines what will look best as far as tree height, and number, spacing, and length of side limbs. Again, you are designing your tree for appearance only. Strength isn’t a concern, because a pollarded tree is never allowed to achieve great height or to grow limbs that are both long and thick. Your young pollarded tree is art in progress; sculpt it accordingly.

Nice proportions

With trunk and permanent side limbs, if present, in place, the pollarded tree needs pruning every winter, or at least every second or third winter. Pruning is easy: Just lop all young stems back to within a half-inch or so of the point where they began growing. Repeatedly lopping stems back to that point is what makes the knob atop the trunk or at the ends of the side limbs.

Prune in early winter if you like your tree to spend the winter with just knobs. Prune just before growth begins in spring if you prefer those knobs graced all winter with a Medusa’s head of sprouts. Either way, the look is interesting, if not pretty.

(This post is adapted from the chapter about pollarding in my book, THE PRUNING BOOK.)

I have a French Pink “Salix caprea” pussy willow that I have pollarded for several years. We had a few very cold seasons with ice storms where I lost a few of the trunks to splitting, but it is still going strong. I remove stems in spring after it flowers to enjoy the catkins. Stems without catkins are used for propagating. I just acquired a 2 ft. chestnut sapling. At what age can they be pollarded?

I would wait at least four or five years.

I’m trying to imagine a pollarded tree growing branches thick enough to serve as firewood. I trust you’ve researched this but it does strike me as unlikely.

It would work but, depending on the tree and growing condition, might require a few years between pruning in order to let sprouts grow old enough to be worth cutting.In England, I saw chestnut coppices that whose growth was harvested (to ground level), with the poles then going to various uses. Such as hop poles or, split four ways and wired together, fencing.

i have a wildly overgrown hibiscus tilaceous that i’ve been thinking of pollarding as a way to try and get some control of it. it was here when i moved into this house and it’s wayyyyyy too large for where it is. normally i would never consider topping a tree, but this thing is like an octopus and i just can’t make sense of how to prune it back like a normal tree form. what do you think?

I’m not familiar with the hibiscus species. If it flowers on new or 1-year-old wood, I’d give it a try.

Great, eye-opening article, thanks. Sooo many people erroneously think thinning back of trees & shrubs are bad for them. I’ve been keeping bonsai for years. I do have a full size Japanese Magnolia in a prominent place in my yard, that I prune every year, removing probably a quarter of the growth. Eventually I’ll be getting too old to do this ‘tho. Last year I think using a pole pruner, I tore my rotator cuff. Now I treated myself to a 14’ A frame ladder. Makes things much easier, but there’s stuff I’ll still need to pole prune. Which makes me think I should be even more drastic w/the pruning of that tree. Sometimes I wonder if all the pruning makes it sucker out even more.

Be careful on a ladder; a fall can do more than shoulder damage.George Bernard Shaw died at the age of 94 due to complications from an injury from falling while pruning a tree.

Also, be careful when pruning magnolias. They don’t like large pruning cuts.

I am having the same issue with pruning an old apple tree. Pruned so many water sprouts last year and it just keeps getting more! I’m 70 years old and a small person. I’m letting the tree go at it this year. Not getting many apples anyway. Deer and turkeys eat them all.