TEASING APART HYDRANGEAS

Good Answer

When someone asks me how they should prune their hydrangea, I give them the answer that most people don’t like to any question “It depends.” What else can I say? It DOES depend. One or more of a few species of hydrangeas commonly make their home in our yards, and you have to approach each, pruning shears or loppers in hand, differently.

Let me tease apart the answer by, first, taking a look a what hydrangea or hydrangeas we may be growing, and then how they grow and flower, which, in turn, speaks to when and where to start snipping away.

Mopheads and Lacecaps, and Oakleafs

If the hydrangea plant in question is a shrub bearing blue or pink flowers, it’s a so-called Bigleaf Hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla). Mopheads types, also called hortensias, bear softball to volleyball size clusters of florets. Lacecap types bear flat-topped cluster of small, hardly conspicuous florets surrounded by rims of showy, larger, 4-petalled florets.

Whether mophead or lacecap, Bigleaf Hydrangeas flowers open from buds they set up the previous year. Those buds are big and fat, in contrast to the skinny buds that grow out to become shoots.

Prune Bigleaf Hydrangea stems as far as the fat buds while the plants are leafless (now, for instance). Right after bloom, cut the stems further back to near ground level.

Problem is that while the plants can stand up to bitter cold, the flower buds can’t, expiring at temperatures below about minus 5° Fahrenheit. Some varieties set their flower buds lower on the stem than do others. Their buds might more reliably stand up to winter cold if plants are mulched in late fall with some loose organic material like straw or arborists’ wood chips.

Pushing Bigleaf Hydrangea growing further north are some recently developed varieties that bloom on new, growing shoots. These new varieties — the first one of which was named Endless Summer — will bloom anywhere. Blossoms on new shoots unfurl later in the season than those on older wood, too late in some gardens (like mine, some years). Cutting back older shoots after they flower fuels a better show from the young, growing shoots.

Oakleaf Hydrangea (H. quercifolia) is another hydrangea that is very cold hardy, except for it flower buds. Flowers sit on the ends of stems in elongated clusters, like cotton candy. Oakleaf Hydrangea can be pruned just like Bigleaf Hydrangea, except that it grows as a large shrub so need not be cut back so much.

Lack of a flowery show from Oakleaf Hydrangea is no loss because a billowing mound or mounds of the oak-like leaves are attractive in their own right through summer, and also in fall, when the leaves turn rich, burgundy red. Even where winter cold would test the reliability of flowering, Oak Leaf Hydrangea is often planted solely for its form and its leaves.

A Beautiful Climber

Years ago, I planted a Climbing Hydrangea (H. animal petiolaris) at the base of the north wall of my home. It took a couple of years or more to get in gear, but now completely clothes that wall. Though leafless through winter, the peeling, light mahogany bark stands prettily against the brick red backdrop.  Soon the stems will be draped in glossy, green leaves and, a little after that, white flowers that stand proud of the wall on short stalks and glow against their dark backdrop like a starry night.

Soon the stems will be draped in glossy, green leaves and, a little after that, white flowers that stand proud of the wall on short stalks and glow against their dark backdrop like a starry night.

This time of year my pruning consists of shortening shorten flower stalks that reach too far out from the wall and vigorous stems that keep trying to sneak around the wall to clothe the rest of the house. Twice in summer I prune stems again to restrain the plant to only the north wall.

Perhaps I’ll plant another Climbing Hydrangea at the base of my 90 foot tall Norway spruce that with age is thinning out. The hydrangea tolerates sun or shade, and can climb a tree without causing harm.

And, Easiest of All

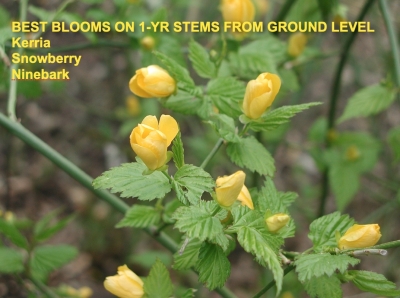

Rounding out this romp through pruning hydrangeas are two of the easiest to prune plants of the species. The first, Smooth Hydrangea (H. arborescens), grows long shoots from ground level, each capped in early summer with half-foot-wide clusters of of white or pastel flowers. To prune, just lop all stems right to the ground in late winter or early spring.

And finally, we come to PeeGee, sometimes called Panicle, Hydrangea (H. paniculata grandiflora), growing like a small tree or large shrub. This one blossoms in late summer on new growth, so if it is going to be pruned, that needs to be done before growth begins.  With that said, Panicle Hydrangea develops a permanent trunk or trunks, making it difficult to reach high into its dense head for pruning. No matter, because the plant flowers quite well with little or no pruning.

With that said, Panicle Hydrangea develops a permanent trunk or trunks, making it difficult to reach high into its dense head for pruning. No matter, because the plant flowers quite well with little or no pruning.

Hydrangea is only one group of closely related plants where species differ in how they are pruned. Roses would be another example; climbing roses are pruned very differently from rambling roses, which are pruned very differently from . . . you get the picture. Clematis also. For more details about the individual pruning needs of these as well as lots of other trees, shrubs, vines, flowers, fruits, and houseplants, and special pruning techniques like pollarding, mowing and scything (yes, that’s pruning!), and espalier, take a look at my book The Pruning Book. It’s available through the usual sources or, signed, directly from me here.

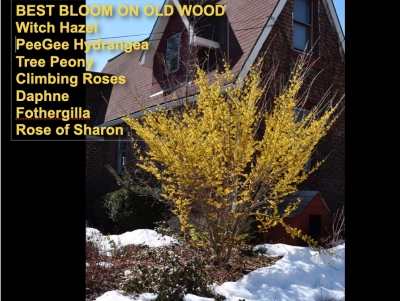

Grouping plants always entails a certain degree of arbitrariness, and because of their disinclination to sucker, a few plants in this category could also be considered “trees,” especially if deliberately trained to one or a few trunks..

Grouping plants always entails a certain degree of arbitrariness, and because of their disinclination to sucker, a few plants in this category could also be considered “trees,” especially if deliberately trained to one or a few trunks..

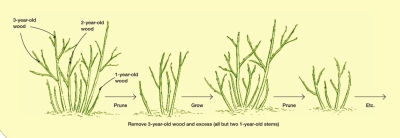

Peer in at the base of the mature plant and you’ll notice wood of various ages growing up from ground level. Begin pruning by cutting away near ground level, some of the very oldest stems. Those oldest stems are also the tallest ones, so these first cuts quickly lower the plant.

Peer in at the base of the mature plant and you’ll notice wood of various ages growing up from ground level. Begin pruning by cutting away near ground level, some of the very oldest stems. Those oldest stems are also the tallest ones, so these first cuts quickly lower the plant.

With flat tops and nearly vertical sides, both hedges are quick and easy to prune. They both widen slightly from head to toe because, quoting from the “hedging” section of my book,

With flat tops and nearly vertical sides, both hedges are quick and easy to prune. They both widen slightly from head to toe because, quoting from the “hedging” section of my book,

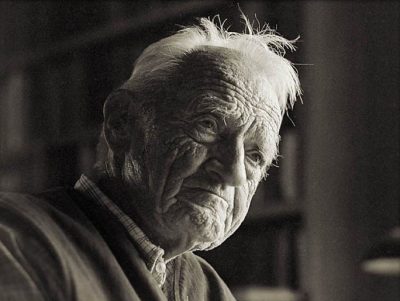

Scott Nearing was a professor of economics, a political activist, a pacifist, a vegetarian and an advocate of simple living. And a gardener. For many of these reasons, he was almost a cult figure back in the 1970s when I, a young man, visited him. He was then known mostly for his book Living the Good Life. I had read the book, and decided to drive 1,000 miles from Madison, Wisconsin to show up on his farm, unannounced, in Harborside, Maine.

Scott Nearing was a professor of economics, a political activist, a pacifist, a vegetarian and an advocate of simple living. And a gardener. For many of these reasons, he was almost a cult figure back in the 1970s when I, a young man, visited him. He was then known mostly for his book Living the Good Life. I had read the book, and decided to drive 1,000 miles from Madison, Wisconsin to show up on his farm, unannounced, in Harborside, Maine. For me, working my field in the quiet of early morning, with the sun low in the sky and grasses still moist from morning dew, is sheer pleasure. A morning dance.

For me, working my field in the quiet of early morning, with the sun low in the sky and grasses still moist from morning dew, is sheer pleasure. A morning dance.

major cuts aimed at keeping the tree open to light and air.

major cuts aimed at keeping the tree open to light and air.

And, of course, for more about pruning, there’s my book,

And, of course, for more about pruning, there’s my book,