STIRRING MY BLOOD, CLEARING (PARTS OF) THE MEADOW

Nearing Influence

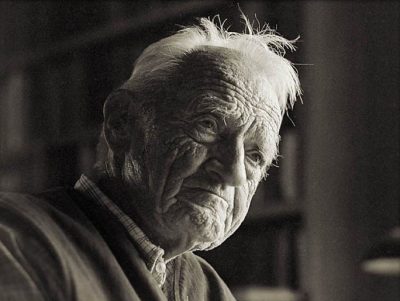

What struck me most about Scott Nearing was his sturdy appearance, arms hanging loosely from broad shoulders, his near perfect teeth, and the deeply creviced wrinkles of his face. He was 91 years old. Looks aside, his influence on me was deep despite the brevity of my visit. Scott Nearing was a professor of economics, a political activist, a pacifist, a vegetarian and an advocate of simple living. And a gardener. For many of these reasons, he was almost a cult figure back in the 1970s when I, a young man, visited him. He was then known mostly for his book Living the Good Life. I had read the book, and decided to drive 1,000 miles from Madison, Wisconsin to show up on his farm, unannounced, in Harborside, Maine.

Scott Nearing was a professor of economics, a political activist, a pacifist, a vegetarian and an advocate of simple living. And a gardener. For many of these reasons, he was almost a cult figure back in the 1970s when I, a young man, visited him. He was then known mostly for his book Living the Good Life. I had read the book, and decided to drive 1,000 miles from Madison, Wisconsin to show up on his farm, unannounced, in Harborside, Maine.

I thought of that visit today as I was swinging my scythe. Would I have been out in the field this morning doing so if I hadn’t made that visit? Scott was a big fan of scything, about which, he wrote, “It’s a first class, fresh-air exercise, that stirs the blood and flexes the muscles, while it clears the meadows.”  For me, working my field in the quiet of early morning, with the sun low in the sky and grasses still moist from morning dew, is sheer pleasure. A morning dance.

For me, working my field in the quiet of early morning, with the sun low in the sky and grasses still moist from morning dew, is sheer pleasure. A morning dance.

From a practical standpoint, no need to worry about waking neighbors with noise of a mower engine, or to worry about getting a mower bogged down in wet spots.

Keeping the Magic

I’ve swung a scythe for many decades. (Not that that makes me an expert in its use; for the first couple of decades I did it wrong. Now, more right.) Two considerations have kept the magic alive.

First, not too much. When I first acquired the acre and a half field to my south, I aimed to keep it a meadow, stemming invasion from woody plants in a natural transition to forest by scything the whole field. Considering the lushness of the vegetation, and how rapidly it grew back, that was a bold undertaking. The result: Something short of sheer pleasure, and tennis elbow.

Salvation came in the form of a small, farm tractor and a brush hog, with which I now mow the bulk of the field once a year.

There’s still plenty to scythe, including areas near my fruit and nut trees, and areas too wet for the tractor. I also scythe selected areas of the field proper, changing yearly to allow scythed sections, whose mowings I gather up, to regenerate. Also important: I limit daily scything to no more than a half hour.

The second consideration is to use the right kind of scythe. The so-called American type scythe, with a curved handle and stamped blade, is put to best use decorating the wall of a barn. I use a so-called Austrian type scythe (purchased from www.scythesupply.com), which usually has a straight handle and is lightweight with a razor sharp, hammered-thin blade. The blade needs periodic hammering (peening) for keeping its taper or for repair, and daily dressing with a whetstone.

Blade length is important. Back when I was working the whole field, the job was made harder because of the 36 inch long blade I was using. Sure, you can cut more with a longer blade, but that was too much lush vegetation to plow through in one swing. Nowadays a 22 inch blade strikes a nice balance, not biting off more than I can “chew.”

No Big Field, No Problem

No need for access to a large field to experience the physical and practical pleasures of scything. For many years, my field was only a portion of my original three-quarter acre property. And no matter how large or small the field, no reason to do as Scott did, to “clear the meadow.” On my small property, I practiced what I called Lawn Nouveau, created, as I detail in my book, The Pruning Book, by sculpting out two tiers of grassy growth. The low grass is maintained just like any other lawn, and kept that way with a lawnmower.

The taller portions need to be scythed but once a year, or more frequently if desired. Raking up mowings from the tall grass portions avoids unsightly clumps or smothering of regrowth. The rakings are good material for mulch or compost. A crisp boundary between tall and low grass keeps everything neat and avoids the appearance of an unmown lawn.

Lawn Nouveau saves me time because the tall grass needs infrequent mowing and there’s no rush to get it done. The tall grass becomes more than just grass as other plant species elbow their way in. Which ones gain foothold depend on the weather, the soil, and frequency of mowing. An attractive mix of Queen Anne’s lace, goldenrod, chicory, and red clover might mingle with the grasses in a dry, sunny area, with ferns, sedges, and buttercups mixing with the grasses in a wetter portion.

Curves at the interface of high and low grass present bold sweeps to carry you along, then pull you forward and push you backward, as you look upon them. Avenues of low grass cut into the tall grass invite exploration — that was the purpose of today’s scything. Thank you Scott.

Albert, our immigrant Hungarian farmhand in the Fifties, scythed timothy now and then as a treat for selected favorites in our herd of a dozen dairy cows. With great skill, he loaded the lush grass onto a three-pronged hay fork like strands of spaghetti. After heaving the load upright, over his head, he trudged from the field to the barn looking like a mini haystack wearing gumboots.

I have about 8 acres of English Walnuts (240 trees) in a grid pattern 40′ x 40′ which leaves a lot of grass, and weeds, between them. For years I regularly mowed the fields between them completely 2 or 3 times a year. Now I just mow, with a 6′ flail mower attached to my tractor, next to the trees forming a nice grid pattern. The birds are happier, I use less diesel and the area under the trees are kept neat and clean.

Way too much work for a scythe though. 🙂

Hi Steve, I agree. How many times per year do you mow with your flail mower? Any production yet from the trees. I have some seedlings I got through NYNG back in 2006. They bore a few nuts last year, hopefully more this year.

Beautiful piece to read at the start of the day.

And the incredible thing about Scott was he started the homesteading life in his early 50’s if I am not mistaken.

The Nearing’s influenced me as well, though I never met them. They wrote of the problems maintaining wood-framed buildings on their farms. Instead, they recommended building with stone and helped spread the work of NY architect Ernest Flagg (1847-1947). Flagg’s firm was known for major projects including the U.S. Naval Academy, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the Singer Tower. Yet on his own property on Staten Island he experimented with methods of building stone cottages, resurrecting ancient techniques for laying stone, rubble, and concrete in wooden forms. In 1922 Flagg published “Small Houses: Their Economic Design and Construction.” Flagg had many ideas that were ahead of his time, including advising against basements and attics, and designing on a standard-sized module. His walls, unfortunately, were not energy efficient for northern climates–though perhaps no worse than other methods. The Nearings influenced my work: I build Passive Houses of masonry, using autoclaved aerated concrete, perfected in Sweden in 1923 and common world-wide though not well-known in the US.

Thanks for that good information. I guess Flagg is the “flag” in flagstone(?) which, if true, should be “flaggstone.”

Alas, flag, as in flat stones, long predates Scott!

I really liked your post; now I wish I’d thought to meet them!

Scott was 94 when I met him and Helen in Harborside. Like you, the visit was short, just overnight for us, and my interactions with them have colored my life since.

My chore was to help Scott unload seaweed from his truck. I was 26, yet Scott could move more than I. His practiced moves were vastly more economical than mine. What a lesson for a young man.

Yes, he was physically amazing. I visited him again when he was about 98. He was sawing firewood when I arrived at his farm.