MAKING THE MOST OF WET GROUND

Have Fun, You Silly Ducks

Wouldn’t you know it: I write about the extended dry spell one week, and the next week, which is now, the rain comes and doesn’t let up. Not that all this rain makes me regret having a drip irrigation system watering my garden. Rainfall could come screeching to a halt and send us into another dry spell.

My five Indian runner ducks offer many advantages here on the farmden, not the least of which is affording me the pleasure of watching creatures that actually enjoy cool, rainy weather. The ducks also are entertaining and decorative, spend much of their days scooping insects and slugs out of the lawn and meadow and into their bills, and, especially when living on that diet of insects, slugs, and greenery, lay very tasty eggs. The downside to ducks is that they are dumb, and don’t know to stay out of the road.

My four chickens offer many of the same advantages as the ducks, except they never seem as at peace with the world as do the ducks. Also, chickens scratch. Scratching at the bases of mulched trees and shrubs exposes roots; scratching elsewhere wrenches young transplants out of the ground.

Chickens abhor rainy weather.

You ‘Shrooms, Also Enjoy This Weather

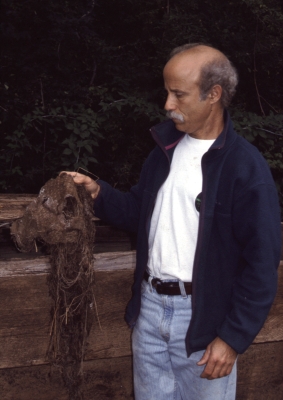

Mushrooms I “planted” last spring are, like the ducks, reveling in this rainy change. “Planting” these mushrooms involved nothing more than pounding short lengths of wooden dowels, purchased with shiitake mushroom spawn growing in them, into numerous holes drilled in freshly cut pin oak logs. A cap of hot wax over each plug sealed in moisture. The 4-foot-long by 4” diameter logs lay in a shady place through summer while being colonized by thin threads of fungal hyphae growing out from the plugs.

This spring was to be the start of a few years of “fruiting,” that is, making mushrooms, the spore bearing structures of fungi that taste so good sautéed with some onions and butter or olive oil. Dry weather of the past few weeks was slowing the mushrooms’ first appearance, so I decided to shock them. Just bouncing the end of a log against a hard surface, such as a sidewalk, sometimes wakes them up. I opted for a water shock treatment, giving the logs a 24 hour soak in a shallow kiddie pool.

Right on schedule, within a week of being soaked, mushrooms began popping out all over the logs. With their ends levered into the horizontal openings of a metal fence gate tipped on its side against a tree, the logs and their attendant mushrooms are cantilevered out, perched above slugs and other organisms that might have enjoyed nibbling the fruits of my labor.

The shock treatment has resulted in a mushroom tsunami. Excess go into the dehydrator, which has them crispy dry and ready for long term storage in about 4 hours. Once the tsunami ends, the fungi need to rest for a month and a half before they’re ready for another shock. Or I can do nothing, and let nature pump out mushrooms more slowly over a longer period of time. Of course, if this rain keeps up — 3 inches in the last couple of days — another tsunami might anyway be in the offing.

And I Can Plant . . . White Strawberries

With the ground thoroughly soaked, it’s a good time to get plants in the ground . . . except in wet, clay soils. Working a wet clay ruins the almost crystalline structure that develops when it is well managed. Then, instead of the small particles aggregating together to make larger particles with larger pores in between them, letting air into the soil, the structure is reduced to only small unaggregated particles. Spaces between these small particles are so small that they draw in water by capillary action, and there’s no room available for air, which plant roots need. Good for pottery, bad for plants. Wait for any clay soil to dry a bit before digging in it, until it crumbles between your fingers with just a little pressure.

My soil is a silt loam that’s been enriched with plenty of compost, which helps aggregation, so I can plant now, even right after rain.

Among the plants I’ll be setting in the ground will be strawberries, right in a garden bed. Strawberries, you wonder? Big deal. But these are alpine strawberries. Okay, many people grow alpine strawberries. But these are white alpine strawberries, white, that is, even when dead ripe.

Alpine strawberries are different from common garden strawberries in that they are a different species (Fragaria vesca), they don’t make runners, and both the plants and fruits are small, the latter about the size of a nickel. Previously, I’ve put a few in pots sitting along my front path for a nibble on the way to the door, or a few at the foot of garden beds, again, for a nibble, here while working in the garden. I want to see how the plants do under the better growing conditions of compost-enriched soil and drip irrigation right in a garden bed.

Alpine strawberries are small but have very intense flavor, which needs to be fully developed before being picked. I especially like the white ones’ flavor, which can develop fully because, being white when ripe, they’re ignored by birds. The variety name Pineapple Crush gives a good approximation of the flavor.