In the Wild

Row, Row, Row My Boat, and Then!

Paddling down a creek — Black Creek in Ulster County, New York — yesterday evening, I was again awed at Mother Nature’s skillful hand with plants. The narrow channel through high grasses bordered along water’s edge was pretty enough. The visual transition from spiky grasses to the placid water surface was softened by pickerelweeds’ (Pontederia cordata) wider foliage up through which rose stalks of blue flowers. Where the channel broadened, flat, green pads of yellow water lotus (Nelumbo lutea) floated on the surface. Night’s approach closed the blossoms, held above the pads on half-foot high stalks, but the flowers’ buttery yellow petals still managed to peek out.

Soon I came upon the real show, as far as I was concerned: fire engine red blossoms of cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis). Coming upon this flower in the wild is startling. Such a red flower in such shade?

So many shade plants bear white flowers which, after all, are most easily seen in reduced light. Only twice before had I come upon cardinal flower in the wild, and both times the blooming plant was in deep, deep shade; it was a rare treat to see such a lively color in the shade.

Though the stream bank was not in deep shade, the cardinal flower was still a treat. And not just one cardinal flower but groups of them here and there along the way.  More than I have ever seen in the wild. (In Chanticleer Garden outside Philadelphia is a wet meadow planted thickly with cardinal flowers.)

More than I have ever seen in the wild. (In Chanticleer Garden outside Philadelphia is a wet meadow planted thickly with cardinal flowers.)

Nature’s Hand

Two other landscape vignettes come quickly to mind when I marvel at natural beauty.

The first are the rocky outcroppings in New Hampshire’s White Mountains; placement of these rocks always looks just right. In addition, the flat areas against the rocks and in rock crevices in which leaves have accumulated to rot down into a humus-y soil provide niches for plants. Among the low growing plants are lowbush blueberries and lingonberries.

Lingonberry in White Mountains

Good job at “edible landscaping” Ms. Nature!

The other vignette was (one of many) in the Adirondack Mountains. Picture a clump of trees and a large boulder. Now picture those trees on top of the boulder, their roots wrapping around and down the bare boulder until finally reaching the ground on which the boulder sat. A scene both pretty and amazing.

But My Fruits and Vegetables are Better(?)

Mother Nature might have it in the landscape design department; not when it comes to growing fruits and vegetables though. There may be some disagreement here: I contend that garden-grown stuff generally tastes better. And for a number of obvious reasons.

In the garden, most of what we grow are named varieties, derived from clones or strains that have been selected from among wild plants, or have been bred. Named varieties generally are less bitter, sweeter, and/or more tender. Perhaps also high-yielding and pest-resistant.

In some cases, “cultivated” plants offer too much of a good thing. Humans long sought to sink their teeth into the sweetest sweet corn, harvesting ears at their peak of perfection and then whisking them into already boiling water to quickly stop the enzymatic conversion of sugars to starches. In the 1950s, a “supersweet” gene was discovered that quadrupled the sugar content of sweet corn — too sweet for me and and lacking the richness of an old-fashioned sweet corn variety such as Golden Bantam.

A nutritional case can be made against cultivated varieties of plants. Studies by the US Department of Agriculture have shown modern fruits and vegetables to be lower in nutrients than those tested 50 or so years ago. Have we excessively mined our soils of minerals? No. Breeding for bulk, along with pushing plant growth along with plenty of water and nitrogen fertilizer, has diluted the goodness in plants.

In Eating on the Wild Side Jo Robinson contends that breeding for sweeter and less bitter plants inadvertently selects for plants lower in many nutrients and phytochemicals.

All this makes a good case for growing more “old-fashioned” varieties, such as heirloom tomatoes and paying closer attention to how plants are fed. (Compost is all my vegetables get.) And perhaps focussing more on what food really tastes like. Does Sugarbuns supersweet really taste like corn. Or a candy bar?

(Compost is all my vegetables get.) And perhaps focussing more on what food really tastes like. Does Sugarbuns supersweet really taste like corn. Or a candy bar?

And eat some wild things. Purslane is abundant and, to some (not me) tasty now. As is pigweed, despite its name, a delicious cooked “green.” I mix it in with kale and chard for a mix of cultivated and wild on the dinner plate.

Descriptions of Rose de Rescht tell how it blossoms repeatedly through the season; not my rose. I finally honed down my rose’s identity from among the choices suggested by a number of rose experts based on photos and descriptions I had sent them.

Descriptions of Rose de Rescht tell how it blossoms repeatedly through the season; not my rose. I finally honed down my rose’s identity from among the choices suggested by a number of rose experts based on photos and descriptions I had sent them. And the fragrance! Intense, and my favorite of all roses. Rose d’Ipsahan is a variety of Damask rose and has the classic fragrance of that category of rose.

And the fragrance! Intense, and my favorite of all roses. Rose d’Ipsahan is a variety of Damask rose and has the classic fragrance of that category of rose. More important, Italian arugula tolerates heat better. As my rows of common arugula are sending up seed stalks, the Italian arugula just keeps pumping out new leaves.

More important, Italian arugula tolerates heat better. As my rows of common arugula are sending up seed stalks, the Italian arugula just keeps pumping out new leaves. The plants were autumn olives (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrubs whose fine qualities I’m reluctant to mention for fear of eliciting scorn from you knowledgable readers.

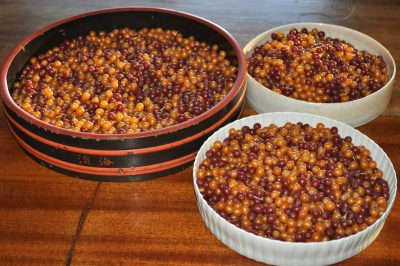

The plants were autumn olives (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrubs whose fine qualities I’m reluctant to mention for fear of eliciting scorn from you knowledgable readers. Those fruits are very puckery until a little after they turn red, but then become quite delicious, and healthful.

Those fruits are very puckery until a little after they turn red, but then become quite delicious, and healthful.

forsythia, mockorange, hydrangea, and any other informal shrub. This technique is known as rejuvenation pruning because, over time, the above ground portion of the shrub is annually rejuvenated. In the case of blueberry, the roots live unfettered year after year but the bush never sports stems more than 6 years old. A perennially youthful blueberry bush can go on like this, bearing well, for decades like this.

forsythia, mockorange, hydrangea, and any other informal shrub. This technique is known as rejuvenation pruning because, over time, the above ground portion of the shrub is annually rejuvenated. In the case of blueberry, the roots live unfettered year after year but the bush never sports stems more than 6 years old. A perennially youthful blueberry bush can go on like this, bearing well, for decades like this. , rose-of-sharon, climbing roses, and flowering quince. These shrubs are among those that perform well year after year on the same old, and always growing older, stems. They also grow few or no suckers each year. The upshot is that thesis shrubs are the easiest to prune: Don’t.

, rose-of-sharon, climbing roses, and flowering quince. These shrubs are among those that perform well year after year on the same old, and always growing older, stems. They also grow few or no suckers each year. The upshot is that thesis shrubs are the easiest to prune: Don’t.

An exhaust fan keeps temperatures from getting too high, which, with lows in the 30s, would wreak havoc with plant growth, at the very least causing lettuce, mustard, and arugula to go to seed and lose quality too soon.

An exhaust fan keeps temperatures from getting too high, which, with lows in the 30s, would wreak havoc with plant growth, at the very least causing lettuce, mustard, and arugula to go to seed and lose quality too soon.

Though not related to clover, oxalis (Oxalis deppei, sometimes called the shamrock plant) leaves are dead ringers for clover leaves — except that all oxalis leaves have four leaflets. And better still, oxalis can be grown as a houseplant, affording you “four-leaf” clovers for year-round proclamations of affection.

Though not related to clover, oxalis (Oxalis deppei, sometimes called the shamrock plant) leaves are dead ringers for clover leaves — except that all oxalis leaves have four leaflets. And better still, oxalis can be grown as a houseplant, affording you “four-leaf” clovers for year-round proclamations of affection. The plant spends summers outdoors in semi-shade near the north wall of my house, and winters indoors on a sunny windowsill. I water it perhaps twice a week, unless I forget.

The plant spends summers outdoors in semi-shade near the north wall of my house, and winters indoors on a sunny windowsill. I water it perhaps twice a week, unless I forget. This orchid is Dendrobium kingianum, which does go under the more user-friendly common name of pink rock orchid. I have also gotten this one to flower — but not every year.

This orchid is Dendrobium kingianum, which does go under the more user-friendly common name of pink rock orchid. I have also gotten this one to flower — but not every year.

And, like the tropical species, flowers are followed by egg-shaped fruits filled with air and seeds around which clings a delectable gelatinous coating. You know the flavor if you’ve ever tasted Hawaiian punch.

And, like the tropical species, flowers are followed by egg-shaped fruits filled with air and seeds around which clings a delectable gelatinous coating. You know the flavor if you’ve ever tasted Hawaiian punch. It’s peak of popularity was in the Middle Ages. And though popular, it was made fun of for it’s appearance; Chaucer called it the “open-arse” fruit.

It’s peak of popularity was in the Middle Ages. And though popular, it was made fun of for it’s appearance; Chaucer called it the “open-arse” fruit.

Mostly I grow it for the novelty of an outdoor orange tree, for the sweetly fragrant blossoms, and for the decorative, green, swirling, recurved spiny stems.

Mostly I grow it for the novelty of an outdoor orange tree, for the sweetly fragrant blossoms, and for the decorative, green, swirling, recurved spiny stems.