MORE AUTUMNAL NEATENING

An Upbeat Closing

I don’t know about you all, but I have a great urge to tidy up my garden this time of year. Partly it’s because doing so leaves one less thing to do in spring and partly because, as Charles Dudley Warner wrote in My Summer in the Garden in 1889, “the closing scenes need not be funereal.” All this tidying up is usually quite enjoyable.

Moist soil – and not too, too many weeds – make weeding fun. Creeping Charlie (also know as gill-over-the-ground) has sneaked into some flower beds. Its creeping stems are not yet well-rooted so one tug with a gloved hand and a bunch of escaping stems slithers back from its travels forward from beneath and among flower plants and shrubs. What remains are occasional tufts of grassy plants, especially crabgrass, easily wrenched out of the ground or coaxed out with my Hori-Hori garden knife.

This tidying is intimate work: me, the soil, weeds, and garden plants at close range. While I’m down there on hands and knees, I’ll also cut back some old stalks of perennial flowers. When everything is cleaned up, I’m going to spread a blanket of chipped wood (free, a “waste” product from arborists) over all bare ground.

The one thing not to do this time of year, as far as tidying up, is pruning. Better to prune after the coldest part of winter is over and closer to when plants can heal wounds.

A Real Crocus, Now

A few weeks ago, I, along with anyone visiting my garden, was wowed by autumn crocuses then in bloom. As I pointed out, they weren’t not true crocuses (they were Colchicum species), they just acted like crocuses – on steroids. Then, a couple of weeks later, I noticed that my true autumn crocuses (that is, the ones that are true Crocus species) were in bloom.

And I did really have to stop and notice them after that most flamboyant show of fake autumn crocuses. These true crocuses (crocii?) are dainty plants, just like spring crocuses, and their colors are subdued: some are pale violet and some are white. In contrast to the fake autumn crocuses, which multiplied like gangbusters, the real autumn crocuses look about dense as when I planted them. Both kinds of crocuses wait until spring to show their leaves.

It’s fortunate that the part of my garden that’s home to autumn crocuses, real and fake — the mulched area beneath the dwarf apple trees — is free of weeds. Otherwise, the real autumn crocuses, being so dainty and lacking a supporting role of leaves, would be swallowed up, visually or for real.

Weed? Perhaps.

Back to weeds . . . I’m trying to see the positive side of all that creeping Charlie I’ve been pulling. Bits of it that have insinuated themselves in amongst the bases of stems of woody shrubs, especially thorny ones like the Frau Dagmar Hastrup rose, are not that much fun to weed out. So what’s good about creeping Charlie?

For one thing, with shiny, round leaves of a deep, forest green color, it’s not a bad looking weed. The flowers are an attractive, purple color although neither big nor prominent enough to make a statement. The otherwise excellent reference book Weeds of the Northeast (Cornell University Press) erroneously states that “the foliage emits a strong mint-like odor when bruised.” That would be nice except that I’ve never noticed that odor and didn’t even when I just ran outside to crush some leaves check up on this statement.

Creeping Charlie grows well in sun or shade, so well that when I worked in agricultural research for Cornell University, I considered the plant as a possible groundcover to replace the relatively sterile herbicide strips in apple orchards. It grows as such beneath my dwarf pear trees.

Creeping Charlie beneath my pear trees

The plant could even be a somewhat ornamental groundcover, making up for any lack of great beauty with its capability to rapid fill in an area and grow only a couple of inches high. You couldn’t ask much more from a plant – except to keep out of some of my flower beds.

I guess two plants per pole, with poles about a foot apart, is too crowded. Next year: one plant per pole.

I guess two plants per pole, with poles about a foot apart, is too crowded. Next year: one plant per pole.

The flavor hints of artichoke, a close relative. None the less, for me the flavor was awful and the stalks were tough. (Cardoon is usually covered to blanche them a few weeks before harvest. Blanching did not make mine more edible.)

The flavor hints of artichoke, a close relative. None the less, for me the flavor was awful and the stalks were tough. (Cardoon is usually covered to blanche them a few weeks before harvest. Blanching did not make mine more edible.)

After a few years of watching the weakened plant recover each season, I made cuttings from some of the stems. The cuttings rooted and the new plants, rather than being grafted, were then growing on their own roots. Even a cold winter wouldn’t kill the roots, living in soil where temperatures are moderated. If the stems died back to ground level, new sprouts would still sport those dark, red blossoms.

After a few years of watching the weakened plant recover each season, I made cuttings from some of the stems. The cuttings rooted and the new plants, rather than being grafted, were then growing on their own roots. Even a cold winter wouldn’t kill the roots, living in soil where temperatures are moderated. If the stems died back to ground level, new sprouts would still sport those dark, red blossoms.

Putting up the net always brings the words of fruit breeder Dr. Elwyn Meader to mind. When I visited him back in the 1980s, the old New Englander, still active in his retirement and growing about an acre of blueberries, among other crops, recounted in his slow, New Hampshire accent, “It takes a patient man to net an acre of blueberries.” Covering my two plantings encompassing a total of about a thousand square feet always creates a little tension.

Putting up the net always brings the words of fruit breeder Dr. Elwyn Meader to mind. When I visited him back in the 1980s, the old New Englander, still active in his retirement and growing about an acre of blueberries, among other crops, recounted in his slow, New Hampshire accent, “It takes a patient man to net an acre of blueberries.” Covering my two plantings encompassing a total of about a thousand square feet always creates a little tension. I now feel like a captain setting sail on an old sailing vessel, with all the sails trim and masts set. Except rather than sails and masts, it’s a blueberry net that’s spread tightly over the permanent, 7-foot-high perimeter of locust posts and side walls of anti-bird, plastic mesh. That netting covers 16 bushes within a 25 foot by 25 foot area. Rebar through holes near the tops of the locust posts keeps that side wall mesh taught and 18” high chicken wire along the bottom keeps rabbits, which love to teethe on that plastic mesh, from doing so.

I now feel like a captain setting sail on an old sailing vessel, with all the sails trim and masts set. Except rather than sails and masts, it’s a blueberry net that’s spread tightly over the permanent, 7-foot-high perimeter of locust posts and side walls of anti-bird, plastic mesh. That netting covers 16 bushes within a 25 foot by 25 foot area. Rebar through holes near the tops of the locust posts keeps that side wall mesh taught and 18” high chicken wire along the bottom keeps rabbits, which love to teethe on that plastic mesh, from doing so. Don’t worry about the birds. They get their fill of berries elsewhere. I don’t net my lowbush blueberries, nor my mulberries or gumis. Birds don’t usually share the mulberries or gumis with me. This year, for some reason, they are sharing.

Don’t worry about the birds. They get their fill of berries elsewhere. I don’t net my lowbush blueberries, nor my mulberries or gumis. Birds don’t usually share the mulberries or gumis with me. This year, for some reason, they are sharing. Juneberries are related to apples and pears, not blueberries, and share some of their kin’s pest problems. Especially in my garden. They’re one fruit that didn’t grow well for me so, years ago, I finally dug the plants up.

Juneberries are related to apples and pears, not blueberries, and share some of their kin’s pest problems. Especially in my garden. They’re one fruit that didn’t grow well for me so, years ago, I finally dug the plants up.

Flowering meads of herbs, flowers, and grasses blanketed the ground beneath most of the orchards, providing — probably unknown back in colonial days — forage for beneficial insects to help protect crop plants.

Flowering meads of herbs, flowers, and grasses blanketed the ground beneath most of the orchards, providing — probably unknown back in colonial days — forage for beneficial insects to help protect crop plants.

My own home is brick; even a few four-foot-high walls around my vegetable garden and in other areas would improve the general appearance — and provide, warmer microclimates for cold-tender plants or early harvests. Not that the rustic locust fencing and arbors enclosing my vegetable garden look unsightly . . . but I’d like some brick walls.

My own home is brick; even a few four-foot-high walls around my vegetable garden and in other areas would improve the general appearance — and provide, warmer microclimates for cold-tender plants or early harvests. Not that the rustic locust fencing and arbors enclosing my vegetable garden look unsightly . . . but I’d like some brick walls.

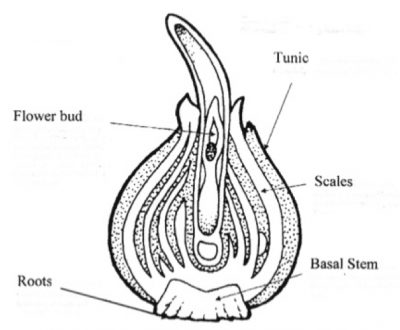

“Knowing what a bulb really is makes it easier to understand how they can multiply so prolifically that their flowering suffers, and how to get them to multiply for our benefit. Dig up a tulip or daffodil and slice it through the middle from the tip to the base. What you see is a series of fleshy scales, which are modified leaves, attached at their bases to a basal plate, off of which grow roots—just like an onion (but, in the case of daffodil, poisonous!). The scales store food for the bulb while it is dormant.

“Knowing what a bulb really is makes it easier to understand how they can multiply so prolifically that their flowering suffers, and how to get them to multiply for our benefit. Dig up a tulip or daffodil and slice it through the middle from the tip to the base. What you see is a series of fleshy scales, which are modified leaves, attached at their bases to a basal plate, off of which grow roots—just like an onion (but, in the case of daffodil, poisonous!). The scales store food for the bulb while it is dormant. Look at where the leaves meet the stems of a tomato vine, a maple tree—any plant, in fact—and you will notice that a bud develops just above that meeting point. Buds likewise develop in a bulb where each fleshy scale meets the stem, which is that bottom plate. On a tomato vine, buds can grow to become shoots; on a bulb, buds can grow to become small bulbs, called bulblets. In time, a bulblet graduates to become a full-fledged bulb that is large enough to flower.”

Look at where the leaves meet the stems of a tomato vine, a maple tree—any plant, in fact—and you will notice that a bud develops just above that meeting point. Buds likewise develop in a bulb where each fleshy scale meets the stem, which is that bottom plate. On a tomato vine, buds can grow to become shoots; on a bulb, buds can grow to become small bulbs, called bulblets. In time, a bulblet graduates to become a full-fledged bulb that is large enough to flower.” Another way is to score the bottom plate with a knife into 6 pie shaped wedges, making each score cut deep enough to hit that growing point.

Another way is to score the bottom plate with a knife into 6 pie shaped wedges, making each score cut deep enough to hit that growing point.  After scoring or scooping, set the bulb in a warm place in dry sand or soil for planting outdoors in a nursery bed in autumn.

After scoring or scooping, set the bulb in a warm place in dry sand or soil for planting outdoors in a nursery bed in autumn. After a year, as many as 60 bulblets might be sprouting from the base of each scooped or scored bulb. Each bulblet does take 4 or 5 years to reach flowering size, but no matter. To quote an old Chinese saying: ‘The longest journey begins with the first step.’”

After a year, as many as 60 bulblets might be sprouting from the base of each scooped or scored bulb. Each bulblet does take 4 or 5 years to reach flowering size, but no matter. To quote an old Chinese saying: ‘The longest journey begins with the first step.’”