Aquatic Matters

/12 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichRain, Rain Go Away; And It Did

Now that this spring’s incessant rains have stopped, we can settle in for dry weather. I hope.

Yes, I should be careful about what I hope for, but plants and people generally enjoy clear, blue, skies. For plants, those days mean plenty of light — actually, more than enough, but no harm done — for photosynthesis, which translates to better flavored fruits and vegetables, and conditions inimical to fungal diseases.

A plant only benefits under these conditions, of course, if it also has enough water at its roots. To that effect, yesterday, in celebration of the second clear, sunny day, I turned on and checked out the drip irrigation system that provides that water to my vegetable plants and blueberry bushes. (With mulches and choice of appropriate plants, all other plants are on their own.)

A plant only benefits under these conditions, of course, if it also has enough water at its roots. To that effect, yesterday, in celebration of the second clear, sunny day, I turned on and checked out the drip irrigation system that provides that water to my vegetable plants and blueberry bushes. (With mulches and choice of appropriate plants, all other plants are on their own.)

Despite the drip irrigation and self-sufficiency of other plants, some hand watering is called for. Trees and shrubs, their first year in the ground, for instance. Also, newly set out vegetable or flower transplants need assistance until their new roots reach a wetting front. The wetting front gets deeper and deeper as a soil dries out. Even with drip irrigation, the wetting front recedes from the ground’s surface with distance from each drip emitter, taking on the shape of overlapping ice cream cones in the soil with their high points right at the surface where an emitter is dripping water. Newly planted seeds likewise need aquatic assistance until they sprout and their roots dip into the wetting front.

A Good Can Is . . .

A hose and a hose wand is one way to get water to needy plants, but for places where it’s not worth the trouble of dragging a hose, a good watering can is just the ticket. You think that a watering can is a watering can? Not so. A quick browse through the web reveals a slew of watering cans differing in style and, hence, ease of use. I’ve tried out a few over the years and, of course, have my favorites.

Size matters. I want a watering can that’s large enough so incessant re-filling isn’t needed for its typical jobs, but not so large as to be unwieldy when filled with water, which weighs in at over 8 pounds per gallon. For houseplants and occasional light jobs, 1.5 gallons works well for me. For more extensive watering, 2 or 3 gallons. The self-serving recommendation in the ad copy for a 3 gallon watering can suggests, “Buy two for a balanced load.” Actually, not a bad idea.

Next, I look at where water exits. Some, usually houseplant watering cans, have merely a spout. Other eater cans have a rose, with little holes for the exiting water.  Especially for watering seed flats and small seedlings, a rose needs to be gentle enough to release water sufficiently fast without washing soil around or crushing small plants.

Especially for watering seed flats and small seedlings, a rose needs to be gentle enough to release water sufficiently fast without washing soil around or crushing small plants.  Some debris is bound to find its way into any watering can and thence to the rose, which needs to be removable and easily cleared. Watch out for thin, plastic roses, which are bound to crack after a few cleanings.

Some debris is bound to find its way into any watering can and thence to the rose, which needs to be removable and easily cleared. Watch out for thin, plastic roses, which are bound to crack after a few cleanings.

Speaking of cleaning, I like a can with an opening large enough for me to reach into. Then I’m able to just scoop out a leaf or a twig that found its way inside without waiting for its journey to the rose. Too big an opening, though, and water splashes all over when the can is carries; one watering can that I saw on the web — an open metal can with a spout — takes this to the extreme!

The attachment of a watering can’s handle affects its balance when carried or used. Ideally, you’re not struggling to counterbalance the can in either case.

Finally, there’s the material out of which the can is made. I’m wary of any plastic watering can. Haws has been manufacturing quality watering cans since 1886 but even their plastic watering cans are not worth the plastic they’re made from; I’ve had two that either cracked or leaked. A copper watering can is expensive but will last just about forever.

And the Winners Are (in My Opinion) . . .

As stated, I have some favorite watering cans. Despite what I wrote in the previous paragraph, three of my four favorites are made by Haws. One is the 1.3 gallon, metal can, more specifically the “Bosmere Haws Slimcan Metal Watering Can, Green”. What to say? Nothing more. It has all the characteristics I seek in a watering can of this volume.

My other two favorites, also Haws, are the same, each with 2 gallon capacity and the same long-reach style and look as the 1.3 gallon Haws. The 2 gallon cans are galvanized, not painted, on their outsides.

(Galvanized steel does eventually rust. A few years ago, one of my 2 gallon Haws developed pinhole leaks. I’m not complaining; the cans are 30+ years old. I reached inside and dripped some Gorilla Glue, which is waterproof and spreads as it dries, over the holes. That repair is still good after 5+ years!)

Up above, I dissed plastic watering cans — yet another of my favorites is a plastic can, a 3 gallon “French Blue Watering Can”. This one is a thick plastic that seems very crack resistant. It also fills the bill in other ways, especially its balance, which is especially important when I’m wielding a can that can hold 24 pounds of water.

One More

Oh, there’s one more watering can that I really like. It’s more like a watering jar than a watering can, with a capacity of about 1/2 cup. It was purchased at a craft fair. And it is copper. I use it to water my bonsai. Mostly, though, I like to look at it.

TIME TRAVEL

/2 Comments/in Flowers, Fruit, Gardening, Vegetables/by Lee Reich18th Century, Here I Come!

Is that me playing the fife? No.

I just returned from time travel one month forward and a couple hundred years backward. Both at the same time! I did this with a trip to Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, where black locust trees were in full bloom, which is about a month ahead of when they will be blooming up here in New York’s Hudson Valley.

The impetus for this time travel was Colonial Williamsburg’s Annual Garden Symposium, at which I was one of the presenters. (I did presentations on espalier fruit plants and on growing fruits in small gardens.)

Williamsburg is a magical place anytime of year, and especially so, for me, in spring. (I first fell in love with the place on a family trip when I was 7 years old; on subsequent visits, I’ve forgone the three-cornered hat I wore on that first trip.)

The governor’s garden

The Symposium included tours through many of the colonial gardens, where we could see, in action, “colonial” gardeners caring for their plants — in many cases using some of the same techniques we use today. Glass cloches, for instance, covered portions of some gardens to hasten warming of the soil for earlier sprouting of seeds.  Flowering meads of herbs, flowers, and grasses blanketed the ground beneath most of the orchards, providing — probably unknown back in colonial days — forage for beneficial insects to help protect crop plants.

Flowering meads of herbs, flowers, and grasses blanketed the ground beneath most of the orchards, providing — probably unknown back in colonial days — forage for beneficial insects to help protect crop plants.

The flowers and vegetables — and fruits in the orchards — are the kinds and varieties grown in colonial times: cardoon, cornflower, chives, cockscomb, pot marigold, nasturtium, hollyhock, Johnny-jump-up, Tennis Ball lettuce, Yellow Crookneck squash, chard, and, of course, corn. Field corn, probably, but also, possibly, sweet corn, which was first given by the Iroquois to settlers in the late 18th century.

Espalier apple trees border vegetable plots

The gardens in Williamsburg provided and provide more than just sustenance. As in the orchards, flowers mingle with crop plants, in this case, vegetables. Most yards in the reconstructed town are one-half acre, with the land separated into sections with white wood fencing. The whole effect is très charmante. Couple that look with the lack of automobiles within the reconstructed town, and the quiet nights illuminated by the soft glow of fire and candle light (supplemented by electric lights with a candle-like glow), and I think I may want to move back into the 18th century.

Wall Envy

One problem I had with Colonial Williamsburg was wall envy. The church on Duke of Gloucester street, the governor’s mansion, and some other public spaces were enclosed by beautiful brick walls capped with functional and decorative rounded brick.

Most of the homes were covered with white-painted, wooden clapboards. The church and the governor’s mansion were made of brick, which, obviously, harmonized well with their brick walls.  My own home is brick; even a few four-foot-high walls around my vegetable garden and in other areas would improve the general appearance — and provide, warmer microclimates for cold-tender plants or early harvests. Not that the rustic locust fencing and arbors enclosing my vegetable garden look unsightly . . . but I’d like some brick walls.

My own home is brick; even a few four-foot-high walls around my vegetable garden and in other areas would improve the general appearance — and provide, warmer microclimates for cold-tender plants or early harvests. Not that the rustic locust fencing and arbors enclosing my vegetable garden look unsightly . . . but I’d like some brick walls.

Incidentally, bricks are made on site at one of the many trades demonstrated within the reconstructed town. I stopped in at the gun shop and stayed soaking up history I never learned in school — how most colonists owned relatively inaccurate muskets which were good enough for hunting and keeping varmints out of gardens, and the real sharpshooters were those with “long rifles,” that is, firearms with rifled barrels that spun their lead shot. But winning a battle wasn’t all about sharpshooters. Long rifles took much longer to reload than muskets, and which side threw the most lead in the air often was what decided who won.

(As part of my immersing myself in 18th century life, I signed up to go to a shooting range to actually fire a flintlock musket. This event, as recorded with 21st century technology, a phone, is documented Musket shooting1, Williamsburg, Musket shooting2, Williamsburg.)

Bricks, rifles, furniture: all these trades are practiced as they would have been in the 18th century. The rifle maker begins his work with nothing more than a block of wood and a block of iron. Four-hundred hours later, he has in hand a finished rifle. Fabric artisans begin with a sheep or flax seeds and some natural dyes. Cabinetmakers begin with trees or rough cut wood. Their tools are the same as those that to which their 18th century forebears had access.

Plant Envy

In addition to my wall envy, I also experienced the usual plant envy that afflicts me when I go south. Southern magnolia tree reach majestic proportions in Williamsburg; I would like to, but cannot, grow them in this cold climate. Crape myrtle is another, for its flowers and its bark mottled in pastel shades; too cold here for this one also.

I did come upon a number of specimens of fringe tree (Chionanthus spp.), with which I’m only vaguely familiar. The fringes of white blossoms dangling in profusion from the branches made me want to become more familiar, i.e. to plant, this shrubby tree. It turns out that I could — and will — grow fringe tree.

Fruit Tree Pruning

/14 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Pruning/by Lee ReichThe Why, and the Easiest

Following last week’s missive about pruning fruiting shrubs, I now move on to pruning my fruiting trees. Again, this is “dormant pruning.” Yes, even though the trees’ flower buds are about to burst or have already done so, their response will still, for a while longer, be that to dormant pruning. I mentioned flower buds, so these plants I’m pruning are mature, bearing plants. The objectives and, hence, pruning of a young tree are another ball game. As is renovative pruning, which is the pruning of long-neglected trees.

I mentioned flower buds, so these plants I’m pruning are mature, bearing plants. The objectives and, hence, pruning of a young tree are another ball game. As is renovative pruning, which is the pruning of long-neglected trees.

Most fruit trees need to be pruned (correctly) every year. Annual pruning keeps these trees healthy and keeps fruit within reach. This pruning also promotes year after year of good harvests (some fruit trees gravitate toward alternating years of feast and famine) and — most important — makes for the most luscious fruits.

With that said, as I’ve pointed out previously, a number of fruit trees can get by with little or no pruning, nothing more than thinning out congested branches, cutting back diseased branches to healthy wood, and removing root sprouts.

Among these easiest to prune fruit trees are persimmon, pawpaw, juneberry, jujube, quince, and medlar. (These are some of the uncommonly delectable fruits covered in my book Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden.) Trees such as juneberry and medlar are quite ornamental, so I also lop off or back wayward branches on these trees to keep them looking pretty.

Fruits Borne on New Shoots and/or 1-Year-Stems

The most straightforward approach to pruning those fruit trees that absolutely benefit from annual (correct) pruning is by grouping them according to their fruit-bearing habits.

Figs, for instance, are unique in being able to bear fruits on new, growing shoots.

Figlets on new growth

So the way to prune a fig tree — with caveats — is to lop back branches, which promotes new, fruit-bearing shoots. But not too, too far or the fruit will take too long to begin ripening. I prune branches of my potted or greenhouse Brown Turkey fig trees only as far back as their permanent trunks of a couple of feet or more in length.

Also, not necessarily all the stems should be pruned back on figs, because some varieties also — or only — bear fruit on one-year-old stems. My San Piero fig, for instance. I typically leave some one-year-old stems to bear an early crop, and drastically shorten others for the crop on new, growing shoots, which begins ripening later.

Peach and nectarine trees also bear on one-year-old stems, so are also pruned rather drastically. I shorten some branches to promote new shoot growth for next year’s harvest. I also remove some branches completely to prevent congestion, allowing branches to bask in sunlight, and breezes to dance among them. When finished, you should be able to throw a cat (figuratively) through the branches without touching them.

I shorten some branches to promote new shoot growth for next year’s harvest. I also remove some branches completely to prevent congestion, allowing branches to bask in sunlight, and breezes to dance among them. When finished, you should be able to throw a cat (figuratively) through the branches without touching them.

Fruits Borne on 1-Year + Older Stems

Fruit trees that bear their fruits on one-year-old as well as on older wood are the next grouping, and include plum, apricot, sweet, and tart cherry. The clusters of flower buds on branches of these trees are known as spurs. (Be careful not to put too much general meaning in “spur” because the word parades under a number of guises in the world of gardening.)

Clusters (spurs) of blossoms on plum

Pruning fruit trees removes some flower buds and potential fruits, which is all for the good because it lets the plant funnel more of its flavor-producing energy into fewer fruits so that those that remain are tastier and larger. Cherries, each of whose small fruits demand little energy, benefit the least of these fruits from such pruning so are the least pruned of the fruits in this category.

Apricot gets the most pruning in this group because its fruit spurs are borne on branches up to 3-years-old. That leaves plums, which get a moderate amount of pruning.

And Even Older Fruit-Bearing Stems

Apples and pears, the final grouping, are the most common tree fruits. Their individual branches each continue to bear flowers and fruits for many years.

Pear spur

Look at an older apple or pear branch and along it you see small, branching stems an inch or less long. These stem clusters are called — and I warned you — “spurs.”

Because their spurs live and bear for a decade or more, apple and pear trees require the least pruning of the fruit trees mentioned.

Then again, spurs do age, eventually becoming overcrowded and decrepit. So I thin out and shorten old spurs so that each has sufficient space and is periodically invigorated with stubby, new growth.

Thinning apple spurs

Exuberant, vertical shoots, known as watersprouts, often pop up on apple or pear branches. Mostly, they are unwanted because they’re not very fruitful and, left alone, will shade other parts of the tree. I cut these off right to their bases.

Pear watersprouts

Even better is to grab hold of watersprouts when you first notice them growing and rip them off with a quick downward pull. “When noticed,” in contrast to all the pruning I just wrote about, is not during the dormant season.

SOIL MATTERS

/3 Comments/in Gardening, Soil, Vegetables/by Lee ReichPlastic on My Bed?!

You’d be surprised if you looked out on my vegetable garden today. Black plastic covers three beds. Black plastic which, for years, I’ve railed against for depriving a soil of oxygen, for its ugliness, for — in contrast to organic mulches — its doing nothing to increase soil humus, and for its clogging landfills. Actually, that insidious blackness covering my beds is black vinyl. But that’s beside the point. Its purpose, like the black plastic against which I’ve railed, is to kill weeds. Not that my garden has many weeds. But this time of year, in some beds, a few more sprout than I’d like to see.

Actually, that insidious blackness covering my beds is black vinyl. But that’s beside the point. Its purpose, like the black plastic against which I’ve railed, is to kill weeds. Not that my garden has many weeds. But this time of year, in some beds, a few more sprout than I’d like to see.

The extra warmth beneath that black vinyl will help those weeds get growing. Except that there’s no light coming through the vinyl, so most weeds will expend their energy reserves and die. And this should not take long, depending on the weather only a couple of weeks or so.

So, first of all, I’m covering the ground for a very limited amount of time.

Furthermore, that the black vinyl is not manufactured specifically for agriculture. It’s recycled billboard signs, available on line from www.billboardtarps.com and other sources. For larger scale use, farmers use the material sold for covering silage.

Old billboard signs or silage covers also improve on black plastic mulch because they are tough. Each time they’ve done their job they can be folded up for storage for future use to be used over and over.

Heavenly Soil

Decades ago, I made a dramatic career shift, veering away from chemistry and diving into agriculture. In addition to commencing graduate studies in soil science and horticulture, I rounded out my education by actually gardening, reading a lot about gardening, and visiting knowledgable gardeners and farmers, including well-known gardener (and better known political and social scientist) of the day, Scott Nearing.

I had just dug my first garden which had a clay soil that turned rock hard as it dried, so I was especially awed, inspired, and admittedly jealous of the soft, crumbly ground in Scott’s garden. What a surprise when someone who had worked with Scott for a long period told me how tough and lean his soil had been when he started the garden. A number of giant compost piles were testimonial to what it takes to improve a soil.

I had just dug my first garden which had a clay soil that turned rock hard as it dried, so I was especially awed, inspired, and admittedly jealous of the soft, crumbly ground in Scott’s garden. What a surprise when someone who had worked with Scott for a long period told me how tough and lean his soil had been when he started the garden. A number of giant compost piles were testimonial to what it takes to improve a soil.

I thought of Scott and his soil as I was planting peas a few days ago. My chocolate-colored soil was so pleasantly soft and moist that I could have made a furrow with just by running my hand along the ground. For a long time I’ve appreciated the fact that the soil in my vegetable garden is as welcoming to seeds and transplants as was Scott’s.

And my dozen or so compost piles, inspired by Scott’s, are testimonial to those efforts.  The soil in my permanent vegetable beds is never turned over with a rototiller or garden fork; instead, every year a layer of compost an inch or so deep is lathered atop each bed, and no one ever sets foot in a bed. That inch of compost snuffs out small weeds, protects the soil surface from washing away, and provides food myriad beneficial microbes (and, in turn, for the vegetable plants).

The soil in my permanent vegetable beds is never turned over with a rototiller or garden fork; instead, every year a layer of compost an inch or so deep is lathered atop each bed, and no one ever sets foot in a bed. That inch of compost snuffs out small weeds, protects the soil surface from washing away, and provides food myriad beneficial microbes (and, in turn, for the vegetable plants).

All sorts of what I consider gimmicky practices attract gardeners and farmers each year: aerated compost teas, biochar, nutrient density farming, fertilization with rock dust, etc. Yet one of the surest ways to improve any soil is with copious amount of organic materials such as, besides compost, animal manures, wood chips, leaves, and other living or were once-living substances. A pitchfork is a very important tool in my garden.

Uh Oh, A Soil Problem

Not all is copacetic here on the farmden.

I make my own potting soil for growing seedlings and larger potted plants. It’s a traditional mix in that it used some real soil. Just about all commercial mixes lack real soil because it’s hard to maintain a sufficient supply that is consistent in its characteristics.

Early this spring, as usual, I sifted together my mix of equal parts compost, peat moss, perlite, and garden soil. This year, NOT as usual, germination of seeds and seedling growth has been very poor. Just today, I re-sowed all my tomato seeds in a freshly made mix from which I excluded soil.

I’m not 100 percent sure that the soil in the mix is the culprit, but it is suspect. I have a small pile of miscellaneous soil that I keep for potting mixes and other uses.  Recent additions to that pile were an old soil pile from a local horse farm and soil from a hole I was digging to create a small duck pond. The latter was poorly aerated subsoil.

Recent additions to that pile were an old soil pile from a local horse farm and soil from a hole I was digging to create a small duck pond. The latter was poorly aerated subsoil.

Seedlings are growing well in my new mix composed only of compost, peat moss, and perlite.

A Podcast and a Workshop

/3 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichI was recently on Joe Lamp’l’s gardening podcast talking about “uncommon fruit.” They’re worth growing because they’re easy, they’re ornaments, and, with few or no pest problems, they’re easy. And they have excellent and unique flavors. Listen to the podcast here.

Also, I’m hosting a pruning workshop at my New Paltz, NY farmden:

Increasing My Hyacinthal Holdings

/3 Comments/in Flowers, Gardening/by Lee ReichHyacinth City

I’ve admitted this before; here’s more evidence of my addiction — to propagating plants. I currently have a seed flat that’s only 4 by 6 inches in size and is home to about 50 hyacinth plants. Obviously, the plants are small. But small and sturdy.

The genesis of all these plants goes back a couple of years when I needed photos for my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden. For the chapter on some aspects of the science of plant propagation and the practical application of that science, I made photos of some methods of multiplying hyacinth bulbs. Here’s an excerpt of that section:

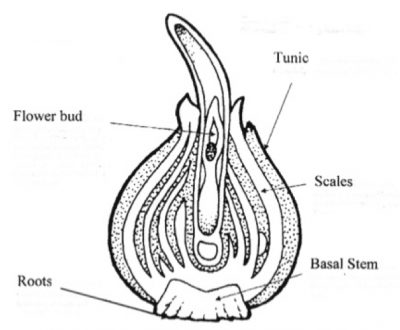

“Knowing what a bulb really is makes it easier to understand how they can multiply so prolifically that their flowering suffers, and how to get them to multiply for our benefit. Dig up a tulip or daffodil and slice it through the middle from the tip to the base. What you see is a series of fleshy scales, which are modified leaves, attached at their bases to a basal plate, off of which grow roots—just like an onion (but, in the case of daffodil, poisonous!). The scales store food for the bulb while it is dormant.

“Knowing what a bulb really is makes it easier to understand how they can multiply so prolifically that their flowering suffers, and how to get them to multiply for our benefit. Dig up a tulip or daffodil and slice it through the middle from the tip to the base. What you see is a series of fleshy scales, which are modified leaves, attached at their bases to a basal plate, off of which grow roots—just like an onion (but, in the case of daffodil, poisonous!). The scales store food for the bulb while it is dormant.

That bottom plate is the actual stem of the plant, a stem that has been telescoped down so that it’s only about a half-inch long. Those fleshy scales are what store food for the bulb, and, depending on the kind of bulb, are nothing more than modified leaves or the thickened bases of leaves.

Look at where the leaves meet the stems of a tomato vine, a maple tree—any plant, in fact—and you will notice that a bud develops just above that meeting point. Buds likewise develop in a bulb where each fleshy scale meets the stem, which is that bottom plate. On a tomato vine, buds can grow to become shoots; on a bulb, buds can grow to become small bulbs, called bulblets. In time, a bulblet graduates to become a full-fledged bulb that is large enough to flower.”

Look at where the leaves meet the stems of a tomato vine, a maple tree—any plant, in fact—and you will notice that a bud develops just above that meeting point. Buds likewise develop in a bulb where each fleshy scale meets the stem, which is that bottom plate. On a tomato vine, buds can grow to become shoots; on a bulb, buds can grow to become small bulbs, called bulblets. In time, a bulblet graduates to become a full-fledged bulb that is large enough to flower.”

Natural Increase

“Let’s see just how the big three flowering bulbs—tulips, daffodils, and hyacinths—grow. With tulips, the main bulb, the one that flowers, disintegrates right after flowering and is replaced by a cluster of new bulblets or bulbs. The mother bulb of a daffodil continues to grow after flowering, at the same time producing offsets of bulbs or bulblets which may remain attached to the mother bulb. Hyacinths grow the same way as daffodils, except for being much more reluctant to make babies.

All those bulblets and bulbs can, in time, crowd each other for light, food, and water, so flowering suffers. When my daffodils, tulips, or hyacinths seem to be making too many leaves and too few flowers, I know it’s time to dig them up and separate all the bulbs and bulblets. The best time for this operation is just as the foliage is dying back in spring or early summer because after that plants are out of sight until the following spring. Replanting can be done immediately or delayed until autumn.”

The Scoop on Propagating Bulbs

“Knowing something about bulb structure also gives me inside information on how to multiply my holdings faster, perhaps to make enough plants for a whole field or a giant flower bed. Merely digging up and planting offsets is one way of doing this. Also, knowing that the bottom plate is a stem and that the offsets come from side buds lets me coax those side buds to grow just as can be done with any other stem.

Pinching out the growing tip of any stem makes side buds grow. One way you get rid of, or ‘pinch out,’ the growing tip of a bulb is to turn the bulb upside down, then scoop out the center of the bottom plate with a spoon or knife.  Another way is to score the bottom plate with a knife into 6 pie shaped wedges, making each score cut deep enough to hit that growing point.

Another way is to score the bottom plate with a knife into 6 pie shaped wedges, making each score cut deep enough to hit that growing point.  After scoring or scooping, set the bulb in a warm place in dry sand or soil for planting outdoors in a nursery bed in autumn.

After scoring or scooping, set the bulb in a warm place in dry sand or soil for planting outdoors in a nursery bed in autumn. After a year, as many as 60 bulblets might be sprouting from the base of each scooped or scored bulb. Each bulblet does take 4 or 5 years to reach flowering size, but no matter. To quote an old Chinese saying: ‘The longest journey begins with the first step.’”

After a year, as many as 60 bulblets might be sprouting from the base of each scooped or scored bulb. Each bulblet does take 4 or 5 years to reach flowering size, but no matter. To quote an old Chinese saying: ‘The longest journey begins with the first step.’”

My little hyacinth bulblets are now in their second season of growth. I’ll keep them growing strongly until their leaves yellow as they go naturally dormant, probably late this spring. Come fall, I’ll dig them all out, separate them, and then plant them out in a nursery bed or else in their permanent homes. I expect aromatic bliss in a couple of years.

And, On Another Note

I was recently a guest on Susan Poizner’s radio show/podcast where we talked about growing uncommon fruits, here at my farmden and in general. Hear it at https://orchardpeople.com/growing-uncommon-fruits/

A Farmdener, That’s Me

/16 Comments/in Design, Flowers, Fruit, Gardening, Vegetables/by Lee ReichA New Word is Introduced

I’d like to introduce the words farmden and farmdener into the English language. I wonder if there are any other farmdeners out there.

What is a farmden? It’s more than a garden, less than a farm. That’s my definition, but it also could be described as a site with more plants and/or land than one person can care for sanely. A gardener and garden gone wild, out of control.

You might sense that I speak from personal experience. I am. My garden started innocently enough: A 30 by 40 foot patch of vegetables, a few apple trees, some flowers, and lawn. That was decades years ago, and in the intervening period, the lawn has grown smaller, the vegetable garden has doubled in size, and the fruit plantings have gone over the top.

Originally, I had less than acreage – 72 hundredths of an acre to be exact. But over the course of 15 years, I did manage to put my fingers onto almost every square foot of that non-acre. Squeezed into that area were 40 varieties of gooseberries, a dozen varieties of apples, a half dozen varieties of grapes, red currants, white currants, black currants, raspberries, mulberries: you get the picture. All that, in addition to my vegetables, flowers, and some shrubbery. But I was still not a farmdener, and my property was not a farmden.

Evolution of My Farmden

The transition from garden to farmden occurred with the purchase of a fertile acre-and-a-half field bordering the south boundary of my property.

With that purchase, I expanded my plantings, rationalizing that because I write about gardening (for magazines, for Associated Press, and for this blog) and host workshops here, I should test and grow a lot of what I write and talk about. So instead of 2 hardy kiwifruit vines such as any normal gardener might grow, I planted 20 vines of a few species and varieties. Instead of 2 pawpaw trees, à la normal gardener, I planted 20 pawpaw trees of few varieties.

Pawpaws, blackcurrants, and hardy kiwis

And how about another dozen apple trees? And chestnuts, filberts, pine nuts (Pinus koreansis is hardy here in New York’s Hudson Valley). Again, you get the picture.

But no, I wasn’t finished. There was always one more plant needing a home, one more piece of ground hungry for a plant. Why not create another vegetable garden; after all, I had just gotten married, and that made another mouth to feed. Why buy vegetables when you have enough land to grow them? And what about winter? A greenhouse full of salad and cooking greens solved that problem, in addition to providing figs in summer and early and late season cucumbers.

And what about winter? A greenhouse full of salad and cooking greens solved that problem, in addition to providing figs in summer and early and late season cucumbers.

I like crown imperial (Fritillaria imperialis) flowers and learned the quirks of propagating them – pack pieces of bulb scales in moist potting soil and subject them to a few months of warm temperatures, then a few weeks of cool temperatures, pot up, plant out. Soon I had not a crown imperial or two such as you might find in most gardens, but dozens of them, and more still coming on.

You might imagine that, despite my plantings, my lawn still grew bigger with that increased acreage. Not so. Most of the acre and a half, except what was devoted to new plantings, became a hayfield that I mowed and helped feed my compost pile. A bit of rationality prompted me to graduate from scything to a small farm tractor for brush hogging that field. (Tennis elbow, the result of excessive scything, also helped with that decision. But I still use the scythe, a high quality Austrian style scythe, to mow parts of the field.)

Present and Future

What I now had – and have – is a farmden. And I am a farmdener. A farmden is not something from which you can earn a living, although I have sold some excess pawpaws, American persimmons, and hardy kiwifruits, mostly for test marketing in my efforts to see whether these fruits are worth promoting for small farms. (They are; flavor sells.)

And my farmden is a great venue for workshops, as long as I point out that participants should pay attention to my plants, not the number of them, because my property is obviously the handiwork of a crazed gardener (or a sane farmdener?). “Don’t try this at home,” I tell participants right off the bat.

I do occasionally still garden. Right next to my terrace is a bed with tree peonies, potentiillas, clove currants, and Signet marigolds, all well-contained by the bricks of the terrace on one side and a low, moss-covered hypertufa wall on the other side. The bed is close to the house and the bed is small. Yesterday I noticed weeds starting to overstep their limit in the bed. I crouched down, started at one side of the bed, and gave it a thorough weeding, literally getting my hands on every square inch of soil. It was fun and it was quick.

Most of my time, though, is spent farmdening. It’s very satisfying, even if it does get crazy sometimes, and it yields a cornucopia of very tasty and healthful fruits and vegetables, many of them planted with an eye to beauty as well as function.

I have vowed not to plant anything more in the hayfield, in large part because it’s so pretty, the soft violet hue from midsummer’s monarda flowers grading over into a golden glow from late summer’s goldenrods. I also promised my daughter, when she was young and enthralled with Laura Ingalls Wilder, that we would leave most of the field as “prairie.” (Now over 30 years old, my daughter no longer yearns for prairies, but I’m keeping my promise.)

I have taken some of the edge off the transition from gardening to farmdening with some help here on the farmden from an occasional helper. Still, I am planning to keep the “den” in farmden.

Future Hopes

/4 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Planning/by Lee ReichTotipotentiality (Is This a Word?)

I was so excited one day a few years back to receive a box full of leafless sticks by mail. The exciting thing about those sticks was that each one of them could grow into a whole new plant from whose branches would eventually hang luscious apples and grapes.

And how did I know the fruits will be luscious? Because a year prior I was at an experimental orchard getting fruit photos for a book I was working on. Of course, I couldn’t help but also taste the fruits, and that’s why Chestnut Crab, Honeygold, Mollie’s Delicious, and King of the Pippins joined the two dozen or so other varieties of apples I already grew. Cayuga White, Bertille Seyve 2758, Steuben, Lakemont, Wapanuka, Himrod, Romulus, and Venus joined my grapes.

It was “totipotence” – of the plants, not me – that allowed me to unlock potential treasures within those mailed sticks. Within a plant, every cell except for reproductive cells has the potential to become a root, a shoot, a flower, a thorn, a fruit, or any other part of a plant. For that matter, the same is true for humans and other animals. All that’s needed are the right conditions to get the various parts to grow – and there’s the rub.

A little art and science puts totipotence to work. In the case of the apples, I grafted those stems onto my existing trees or onto small rootstocks. Existing trees or rootstocks provide nothing more than roots to nourish shoots that will eventually sprout from the sticks. The plant beyond the graft remains genetically that of whatever variety is grafted upon the rootstock.  Grape sticks got plunged into the ground where they grew their own roots, shoots, and everything else. Apples aren’t so amenable to growing their own roots.

Grape sticks got plunged into the ground where they grew their own roots, shoots, and everything else. Apples aren’t so amenable to growing their own roots.

I generally wait to graft or set cuttings until early spring. Warmth awakens those sticks. Until then, they’re kept cool and dormant.

I planned on tasting the first fruits of my labors within about 3 years.

Out With the New, In With the Newer

None of those varieties I received as leafless sticks are still with me.

Because of pests, apples are especially problematic to grow here so I subsequently narrowed down my apple holdings to trees of my few very favorite varieties: Macoun, Liberty, Ashmeads Kernel, Pitmaston Pineapple, and Hudson’s Golden Gem.

Except for Wapanuka, the grapes never tasted as good here as they did at that experimental orchard. Is it because of terroir? Was it the setting that influenced my tastebuds? Anyway, they’ve been replaced by other “sticks” — Somerset Seedless, Glenora, and Vanessa — that now bear fruit in the rows with my older, established vines..

Murphy’s Law, Amendments

Although I have gardened for decades, I still consider myself a relative newbie to greenhouse gardening. Sure, I’ve dabbled in various greenhouses over the years but I’ve only experienced the intimate vagaries of my own greenhouse for the last 18 years. It took time for it to finally dawn on me that Murphy’s Law – “Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong” – also applies in the greenhouse. In retrospect, why wouldn’t it?

I’ve had my brushes with the law. For instance, one winter evening a few years ago when I went to pick some lettuce for a salad; methinks, “Hmmm, quite nippy in here.” But then, except from when sunlight is beaming through the plastic covering, it’s always nippy in there in winter. Salad greens, kale, chard, and celery thrive in those cool temperatures, which dip into the mid-30s before the propane heater kicks on. (The in-ground figs stay dormant and leafless.)

Still, temperatures felt nippier than normal so I checked the thermometer to confirm and, yes, it was getting down to the high 20s. I then checked the propane heater; it ignored me as I twisted the dial on the thermostat clockwise.

Right then and there, I proposed an amendment to Murphy’s Law: “Anything that can go wrong, will go wrong — at the worst possible time!” Temperatures the night before had plummeted below zero. No wonder a water line had burst that morning. I had assumed that frigid temperatures had made only that corner of the greenhouse too cold. Fortunately, after a lot of nail biting, the gas man and I determined that the pilot light had blown out in the heater. Most plants survived the cold.

One event does not a Law make. Thinking back to another Murphy event, I remember an even more serious freeze in the greenhouse. One day everything looked verdant; the next day mush. (The gas company had forgotten to re-fill the propane tank.) After that event, I rigged up a backup electric heater, just in case temperatures dropped below freezing.

Perhaps yet another Murphy’s Law Amendment is needed. On the night of a more recent freeze, the electric heater was, of course, hooked up. Except it wasn’t poised for warmth. The thermostat was directing it to wake up, but I had forgotten to flip the heater’s “on-off” switch to “on.” My bad.

Live and learn: The sun is now setting, the mercury is now plummeting, but no fear of high winds blowing out the pilot light again. I subsequently upgraded the heater for a pilot light-less one. But when I go out to pick some lettuce, celery, and parsley, I will: Check propane heater, check electric heater, check that the water line is off. And remember to latch the door closed on my way out — really!