INTO THE WOODS

Forest Garden Skeptic

“Forest gardening” or “agroforestry” has increasing appeal, and I can see why. You have a forest in which you plant a number of fruit and nut trees and bushes, and perennial vegetables, and then, with little further effort, harvest your bounty year after year. No annual raising of vegetable seedlings. Little weeding, No pests. Harmony with nature. (No need for an estate-size forest; Robert Hart, one of the fathers of forest gardening, forest gardened about 0.1 acre or 5000 square feet.)

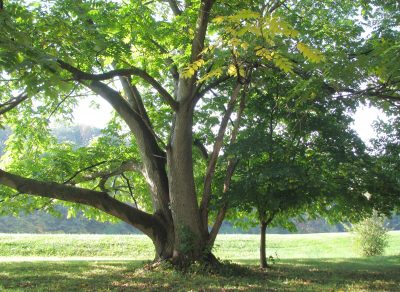

Is this a forest garden?

Do I sound a bit skeptical? Yes, a bit. Except in tropical climates, forest gardening would provide only a nibble here and there, not a significant contribution to the diet in terms of vitamins and bulk. A major limitation in temperate climates is that most fruit and nut trees require abundant sunlight to remain healthy; the same goes for most vegetables.

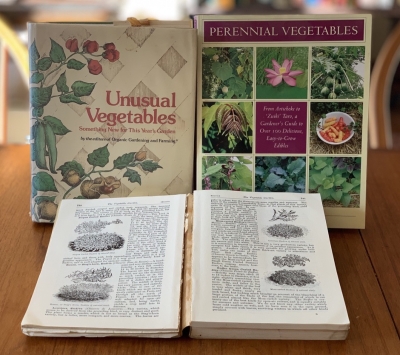

The palette of perennial vegetables in temperate climates is very limited, especially if you narrow the field down to those tolerating shade. I’m also not so sure that weeding would be minimal; very invasive Japanese stilt grass has been spreading a verdant carpet on many a forest floor whether or not dappled by sunlight.

The case could be made — has been made — that some of the dietary vegetable component could be grown on trees. Robert Hart wrote of salads using linden tree leaves instead of annuals such as lettuce and arugula. I’ll admit that I’ve never chewed on a linden leaf. (I’ll give it a try as soon as I come upon one that has leafed out.) My guess is that its taste and texture would leave much to desire.

And how about squirrels? I grow nuts, and part of my controlling them involves maintaining meadow conditions around the trees. This exposes them to predators, including me and my dogs, without their having tree tops to retreat to and travel within. Unprotected, I’ve had nut plants stripped clean by squirrels.

The book Edible Forest Gardens by Dave Jacke offers a very thorough exploration of forest gardening.

But Did I Plant a Forest Garden?

I’ve actually planted a forest garden! Well, perhaps not a forest garden. Over 20 years ago, I did plant a mini-forest. My forest, only about 300 square feet, was originally planted for fun (I like to plant trees), for aesthetics, and for some nutrition. So far I’ve reaped immense visual rewards for my effort.

Here’s what I planted: Bordering a swale that is rushing with water during spring melt and periods of heavy rain went four river birch (Betula nigra) trees. They evidently enjoy the location for they’re now each multiple trunked with attractively brown, peeling bark and towering to about 60 feet in height.

River birch

I also planted 3 sugar maple trees to provide sap for maple syrup for the future. The future is now (except I no longer use enough maple syrup to justify tapping them.) I also planted a white oak (Quercus alba), whose sturdy limbs, I figured, would slowly spread wide with grandeur in about 150 years, after the maples and birches were perhaps long gone. Unfortunately, the white oak died, probably due to winter cold; its provenance was a warmer winter climate. My mistake.

I also planted a white oak (Quercus alba), whose sturdy limbs, I figured, would slowly spread wide with grandeur in about 150 years, after the maples and birches were perhaps long gone. Unfortunately, the white oak died, probably due to winter cold; its provenance was a warmer winter climate. My mistake.

Since that initial planting, I’ve also planted a named variety of buartnut (Juglans x bixbyi), which is a hybrid of Japanese heartnut and our native butternut.

Buartnut (not mine, yet)

I hadn’t realized it, but that tree has grown very fast and now spreads its limbs wide in much that habit as a white oak. The other two trees that I planted are named varieties of shellback hickory (Carya laciniosa). These trees are slow growing but eventually will offer good tasting nuts. They’re quite pretty, even now, with their fat buds.

A Vegetable Also

What about vegetables in my mini-forest? They were not part of my original plan. It turns out that ramps, a delicious onion relative, a native, which I’ve been growing for a few years beneath some pawpaw trees, are spring ephemerals. Spring ephemerals are perennial plants that emerge quickly in spring to soak up sunlight before its blocked by leaves on trees, then grow and reproduce before the tops die back to the ground.

Ramps (Allium tricoccum) are perfect forest vegetable, so I wanted to make the ground beneath my mini forest more forest-y before moving the ramps from beneath the pawpaws. Nothing fancy. All I did was to haul in enough leaves to blanket the ground in the planting area a few inches deep. That leafy mulch will suppress competition from weeds and add organic matter to the soil.

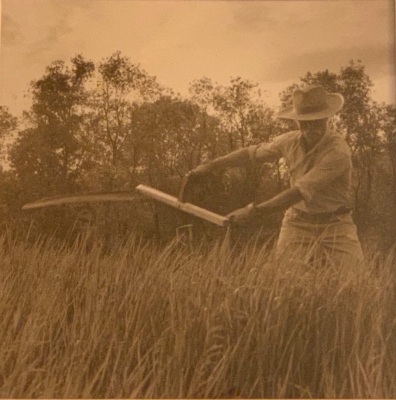

Collecting ramps for transplanting

In just a few years, the ramps will be sufficiently established to provide good eating, perhaps along with some buartnuts and hickory nuts, all from my forest(?) garden.

Drip Opportunity

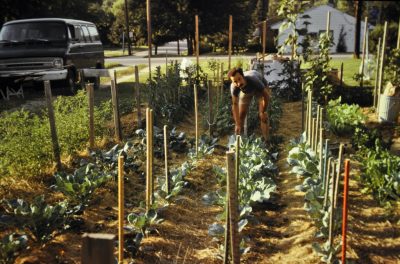

I’m looking for a site within 20-30 minutes of New Paltz, NY in which to hold a drip irrigation workshop. What I need is a vegetable garden in beds (not necessarily raised beds) for which I would design a drip system. Workshop attendees I would install the system after learning about drip irrigation. Host pays fo materials. Contact me if interested.

I guess two plants per pole, with poles about a foot apart, is too crowded. Next year: one plant per pole.

I guess two plants per pole, with poles about a foot apart, is too crowded. Next year: one plant per pole.