Pests Pesky and Not So

Memories

The tumbled over Red Russian kale seedling brought back old memories. It was like seeing the work of an old friend — or, rather, an old enemy. It’s been so long since I’ve seen a cutworm at work in my garden that I couldn’t even get angry at it.

Cutworm and friend’s broccoli

I scratched around at the base of the plant to try and find the bugger. Too late, fortunately for him or her because its fate would then have been a two-finger crush. The cutworm in a friend’s garden I visited last spring was not so lucky.

The bad thing about cutworms are that they chop down young, tender seedlings. At that age, seedlings’ roots lack the energy to grow new leaves; the plants die. (I wonder how the cutworm benefits from lopping back the seedling; the felled plant usually doesn’t get eaten.)

My kale plant

The good thing about cutworms is that, in my experience, they are few and far between — just one or two every few years.

Also, on a garden scale, they’re easy to control, if needed. They prepare for their meal by wrapping their bodies around the plant stems. When I feared them more, I would cut cardboard rolls at the center of paper towels or toilet tissue into lengths of about 1-1/2 inches long, slit one site, fit it around the seedling, press it into the ground, and tape it back closed. A bit tedious, I must admit.

Then I read that cutworms can be fooled. They only attack soft, young seedlings. A thin stick or toothpick slid partway into the ground next to a seedling makes a cutworm think the plant is a woody plant and, hence, out of its league. Since I didn’t find the culprit in my garden, I slid thin sticks next to nearby seedlings. For my friend’s garden, I returned from her kitchen with a handful of toothpicks and instructed her teenage son what to do with them.

Except for today, I haven’t taken precautionary measures against cutworms for many years. Especially every morning, robins, catbirds, and mourning doves are pecking around the ground in my garden; I suspect that’s one explanation for the lack of cutworms.

A Good Parasite

A week or so ago, I saw another old “friend” in the vegetable garden. I noticed that leaflets had been thoroughly stripped from one region of one tomato plant. Obviously, a tomato hornworm, a voracious and rapid diner, was lurking somewhere amongst the existing foliage. A cause for panic? No!

The culprit, a green, velvety caterpillar with widely spaced, thin white stripes and some rows of black dots, is undoubtedly intimidating.

Besides its voracious appetite — you can hear it chomping away — it is the size of an adult pinky.

Still, not to worry. Like cutworms, tomato hornworms turn up in my garden only every few years. And again, like hornworms, they seem to arrive, or show evidence, solo.

I did not reach out to crush the hornworm when I saw her because her back was riddled with what looked like grains of white rice standing on end. Those “rice kernels” are actually the eggs of a parasite that in short order turns that beautiful body to an ugly mush. It’s a dog eat dog world out there.

A Call for Action with This One

I can’t be so complacent about all pests that can turn up in my vegetable garden. Probably the worst one that causes problems every year is one or more of the caterpillars now, as I write, chewing away on the leaves of cabbage and its kin. The symptoms are quite evident: holy . . . whoops, holey . . . leaves upon which is deposited dark green caterpillar poop.

A close eye is needed on cabbage and its kin because one day there’ll be no damage and next time you look, leaves are riddled with holes and poop.

A close eye is needed on cabbage and its kin because one day there’ll be no damage and next time you look, leaves are riddled with holes and poop.

And then, action is necessary. Hand-picking is one option. I choose to use the biological insecticide B.t., short for Bacillus thurengiensis and commonly sold under such names a Dipel or Thuricide. It should be used with restraint because the insects can — and, in some cases, have — developed resistance to this useful pesticide which is very specific in what it harms and what it leaves alone.

Now that I mention it, excuse me for 10 minutes while I mix up a batch of spray for my cabbages, Brussels sprouts, and kale plants . . .

I’m back. The caterpillars seem to prefer cabbage, Brussels sprouts, and cauliflower over kale, which is fine with me because kale is my favorite of the lot.

Many predators, including certain wasps and beetles, diseases, birds, and bats, keep these caterpillar pests under control. Evidently not enough, though, in my garden.

Occasional, light sprinklings of soil add bulk to the finished mix. Occasional, sprinklings of ground limestone keep planted ground, final stop for the compost, in the right pH range.

Occasional, light sprinklings of soil add bulk to the finished mix. Occasional, sprinklings of ground limestone keep planted ground, final stop for the compost, in the right pH range.

I train my tomato plants to stakes and single stems, which allows me to set plants only 18 inches apart and harvest lots of fruit by utilizing the third dimension: up. At least weekly, I snap (if early morning, when shoots are turgid) or prune (later in the day, when shoots are flaccid) off all suckers and tie the main stems to their metal conduit supports.

I train my tomato plants to stakes and single stems, which allows me to set plants only 18 inches apart and harvest lots of fruit by utilizing the third dimension: up. At least weekly, I snap (if early morning, when shoots are turgid) or prune (later in the day, when shoots are flaccid) off all suckers and tie the main stems to their metal conduit supports. I lop wayward shoots either right back to their origin or, in hope of their forming “spurs” on which will hang future fruits, back to the whorl of leaves near the bases of the shoots.

I lop wayward shoots either right back to their origin or, in hope of their forming “spurs” on which will hang future fruits, back to the whorl of leaves near the bases of the shoots. Newly planted trees and shrubs are another story. This first year, while their roots are spreading out in the ground, is critical for them. I make a list of these plants each spring and then water them weekly by hand all summer long unless the skies do the job for me (as measured in a rain gauge because what seems like a heavy rainfall often has dropped surprisingly little water).

Newly planted trees and shrubs are another story. This first year, while their roots are spreading out in the ground, is critical for them. I make a list of these plants each spring and then water them weekly by hand all summer long unless the skies do the job for me (as measured in a rain gauge because what seems like a heavy rainfall often has dropped surprisingly little water). Not only vegetables get this treatment. Buy a packet of seeds of delphinium, pinks, or some other perennial, sow them now, overwinter them in a cool place with good light, or a cold (but not too cold) place with very little light, and the result is enough plants for a sweeping field of blue or pink next year. Sown in the spring, they won’t bloom until their second season even though they’ll need lots of space that whole first season.

Not only vegetables get this treatment. Buy a packet of seeds of delphinium, pinks, or some other perennial, sow them now, overwinter them in a cool place with good light, or a cold (but not too cold) place with very little light, and the result is enough plants for a sweeping field of blue or pink next year. Sown in the spring, they won’t bloom until their second season even though they’ll need lots of space that whole first season. Every time I look at a weed, I’m thinking how it’s either sending roots further afield underground or is flowering (or will flower) to scatter its seed. Much of gardening isn’t about the here and now, so I also weed now for less weeds next season. It’s worth it.

Every time I look at a weed, I’m thinking how it’s either sending roots further afield underground or is flowering (or will flower) to scatter its seed. Much of gardening isn’t about the here and now, so I also weed now for less weeds next season. It’s worth it.

They’ve been making headway across the Northeast since arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1992. But my lilies still look fine and, yes, I do still see some of those beetles. Perhaps one of the natural predators released in Rhode Island years ago has joined the crowd here, minimizing damage.

They’ve been making headway across the Northeast since arriving in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1992. But my lilies still look fine and, yes, I do still see some of those beetles. Perhaps one of the natural predators released in Rhode Island years ago has joined the crowd here, minimizing damage. Then, about 10 years later, and since then, they’ve showed up on schedule, which is now, but then disappeared for the rest of the season. Did they go off to greener pastures? Did they succumb to soil nematodes or fungi?

Then, about 10 years later, and since then, they’ve showed up on schedule, which is now, but then disappeared for the rest of the season. Did they go off to greener pastures? Did they succumb to soil nematodes or fungi? Although chemical, mechanical, and biological controls are still under development, this pest has not put an end to my blueberry-eating days. Thanks to some bait and kill traps developed by Cornell’s Peter Jentsch, damage has been kept to a minimum.

Although chemical, mechanical, and biological controls are still under development, this pest has not put an end to my blueberry-eating days. Thanks to some bait and kill traps developed by Cornell’s Peter Jentsch, damage has been kept to a minimum. To make matters worse, it also exudes a sticky honeydew which falls on any nearby surface (other leaves, lawn furniture, etc.) and, worse yet, becomes food for a fungus than turns that stickiness dark.

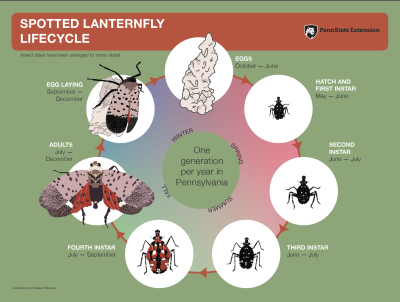

To make matters worse, it also exudes a sticky honeydew which falls on any nearby surface (other leaves, lawn furniture, etc.) and, worse yet, becomes food for a fungus than turns that stickiness dark. In spring, nymphs hatch and climb trees in search of soft, new growth. The one-inch long adults emerge around now; they’re very mobile, usually jumping but also capable of flying, which is when their spread wings display their bright red color. With wings folded, the insects are mostly gray wings with dark spots.

In spring, nymphs hatch and climb trees in search of soft, new growth. The one-inch long adults emerge around now; they’re very mobile, usually jumping but also capable of flying, which is when their spread wings display their bright red color. With wings folded, the insects are mostly gray wings with dark spots. A few natural predators, such as spiders and praying mantises, feast on SLF, but not enough. What to do? There are a few approaches.

A few natural predators, such as spiders and praying mantises, feast on SLF, but not enough. What to do? There are a few approaches. This ancient variety, elongated and with a black skin, has been grown almost exclusively near the Pardailhan region of France. Why am I growing it? The flavor is allegedly sweeter than most turnips, reminiscent of hazelnut or chestnut.

This ancient variety, elongated and with a black skin, has been grown almost exclusively near the Pardailhan region of France. Why am I growing it? The flavor is allegedly sweeter than most turnips, reminiscent of hazelnut or chestnut. Next year I can expect a vine growing 6 to 9 feet high and which is both decorative and tolerates some shade. What’s not to like? (I’ll report back with the flavor.)

Next year I can expect a vine growing 6 to 9 feet high and which is both decorative and tolerates some shade. What’s not to like? (I’ll report back with the flavor.) Later in the season, cluster of bulbs form, similar to shallots, although forming larger bulbs. They can overwinter and make new onion greens and bulbs the following years.

Later in the season, cluster of bulbs form, similar to shallots, although forming larger bulbs. They can overwinter and make new onion greens and bulbs the following years.

The problem was separating the small tubers from soil and small stones. I have a plan this time around — more about this at harvest time.

The problem was separating the small tubers from soil and small stones. I have a plan this time around — more about this at harvest time.

The next bins weren’t bins but just carefully stacked layers of ingredients, mostly horse manure, hay, and garden and kitchen gleanings. And then there was my three-sided bin made of slabwood.

The next bins weren’t bins but just carefully stacked layers of ingredients, mostly horse manure, hay, and garden and kitchen gleanings. And then there was my three-sided bin made of slabwood.

Which brings me to my current bin which, now, after many years of use, I consider nearly perfect. Instead of hemlock boards, these bins are made from “composite lumber.” Manufactured mostly from recycled materials, such as scrap wood, sawdust, and old plastic bags, composite lumber is used for decking so should last a long, long time.

Which brings me to my current bin which, now, after many years of use, I consider nearly perfect. Instead of hemlock boards, these bins are made from “composite lumber.” Manufactured mostly from recycled materials, such as scrap wood, sawdust, and old plastic bags, composite lumber is used for decking so should last a long, long time. When finished, I ripped one board of the bin full length down its center to provide two bottom boards so that the bottom edges of all 4 sides of the bin would sit right against on the ground.

When finished, I ripped one board of the bin full length down its center to provide two bottom boards so that the bottom edges of all 4 sides of the bin would sit right against on the ground. Before setting up a bin, I lay 1/2” hardware cloth on the ground to help keep at bay rodents that might try to crawl in from below.

Before setting up a bin, I lay 1/2” hardware cloth on the ground to help keep at bay rodents that might try to crawl in from below. With the Lincoln-log style design, the bin need be only as high as the material within while the pile is being built, and then “unbuilt” gradually as I removed the finished compost.

With the Lincoln-log style design, the bin need be only as high as the material within while the pile is being built, and then “unbuilt” gradually as I removed the finished compost.

My first inclination, before even identifying chestnut blight as the culprit, was to lop off the two limbs. Once I got up close and personal with the tree, the tell-tale orange areas within cracks in the bark stared me in the face.

My first inclination, before even identifying chestnut blight as the culprit, was to lop off the two limbs. Once I got up close and personal with the tree, the tell-tale orange areas within cracks in the bark stared me in the face. There is no cure for chestnut blight. Removing infected wood does remove a source of inoculum to limit its spread. In Europe, the disease has been limited by hypovirulence, a virus (CHV1) that attacks the blight fungus. Some success has been achieved using a naturally occurring virus found on blighted trees in Michigan.

There is no cure for chestnut blight. Removing infected wood does remove a source of inoculum to limit its spread. In Europe, the disease has been limited by hypovirulence, a virus (CHV1) that attacks the blight fungus. Some success has been achieved using a naturally occurring virus found on blighted trees in Michigan.

Yet even on the clearest, sunny day — and especially on that kind of day — a dark cloud hangs overhead. Hay fever, literally from hay that is, grasses; and nonliterally, from tree pollen.

Yet even on the clearest, sunny day — and especially on that kind of day — a dark cloud hangs overhead. Hay fever, literally from hay that is, grasses; and nonliterally, from tree pollen. Multiflora rose puts on its show to attract pollinators, such as bees, which transfer pollen from one plant to the next. Hay fever is from airborne pollen blown about by wind, so the flowers of these allergen plants have no need to attract insect pollinators. The non-showy culprits this time of year are grasses and oaks.

Multiflora rose puts on its show to attract pollinators, such as bees, which transfer pollen from one plant to the next. Hay fever is from airborne pollen blown about by wind, so the flowers of these allergen plants have no need to attract insect pollinators. The non-showy culprits this time of year are grasses and oaks.