Mulberries, Still

I finally am getting to eat some ripe mulberries this year, and they were — and are — very, very good. The wait wasn’t because the tree was too young. And anyway, mulberries are very quick to bear fruit, often the year after planting.

I got to eat fruit from my tree this year because resident birds have been kind enough to share some with me. Of course, it was not really kindness on their part.  Birds also eat fruit for their juiciness, and the past weeks and weeks of abundant rainfall probably satisfied some of that need. The only other year I had plenty of mulberries — much more than this year — was a few years ago when 17-year cicadas descended upon here. All summer I awoke to their grating cacophony, but did feast on mulberries as birds feasted on the cicadas.

Birds also eat fruit for their juiciness, and the past weeks and weeks of abundant rainfall probably satisfied some of that need. The only other year I had plenty of mulberries — much more than this year — was a few years ago when 17-year cicadas descended upon here. All summer I awoke to their grating cacophony, but did feast on mulberries as birds feasted on the cicadas.

You might think it late in the season for mulberry fruits, which started ripening back in early July, to still be ripening. The variety name of my tree says it all: Illinois Everbearing. Not only is this variety everbearing, but it also has a very fine flavor, much better than the run-of-the-mill and ubiquitous wild mulberries whose fruit is usually too cloying. Illinois Everbearing’s sweetness is balanced with a bit of refreshing tartness.

Good as it is, Illinois Everbearing’s fruits cannot compare with that of black mulberry. The “black” refers to the species, Morus nigra. Illinois Everbearing is a hybrid of our native red mulberry, M. rubra, and white mulberry, M. alba, an Asian species that was introduced into our country about 200 years ago, liked it here, and mated with the native species. Black mulberry can only be grown in Mediterranean climates, so mine, in a large pot, bears only a handful of berries each year.

Some people contend that black mulberries adaptability is more widespread than mild winter climates. I have my doubts but I am going to graft a branch from my little tree onto some stems of some wild mulberries and see what happens. (The wild mulberries might either be white or red mulberries, or natural hybrids of the two; the color designations have nothing to do with the color of fruit a tree bears.)

I’m happy enough with the long season, good flavor, and occasional harvest of Illinois Everbearing. Plus, it’s a pretty tree, and large, so the branches are now beyond reach of deer, who love to eat mulberry leaves.

I devote a whole chapter to mulberries, white, red, and black, in my book Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden.

Basil, Uh Oh

Bringing my eyes down from the dark mulberries to ground level, and walking over to the vegetable garden, I take a close look at this year’s basil. Hmm. Very slight yellowing of some of the leaves. Could it be . . . ? Yes, turning over one of those slightly chlorotic leaves I see tell-tale purplish brown spores, indicating downy mildew disease.

A relative newcomer to the garden scene, basil downy mildew (a different pathogen than cucumber downy mildew, grape downy mildew, etc.) arrived on the East Coast in 2007, made it to the West Coast by 2009, and to Hawaii by 2011. It hitchhike around on infected seed, infected plants, and infected leaves.

Basil downy mildew, leaf underside

Some organic fungicides are allowed for controlling the scourge, but my basil mingles so intimately with other plants in the vegetable garden that I don’t consider that an option. Fortunately, other controls are feasible.

One thing would be to not mingle my basil so intimately with other plants. Sunlight is one nemesis of the mildew, as with most fungi. Better air circulation would also lower the humidity around the plants and speed drying of the foliage, also not to the liking of the mildew fungi.

Going one step further, Dr. Meg McGrath of Cornell University suggests growing basil in pots. Plants can be whisked under cover on cool nights, when dew threatens, or during rain or cloudy conditions.

Starting off with clean seed or plants would also limit infection. Not totally, though. Although the fungus does not overwinter in cold regions, given good (for the fungus) conditions, it can hitchhike up here over hundreds of miles.

Breeders are hard at work developing resistant varieties of basil, with some success. Among the resistant varieties are Amazel (shouldn’t the name be Amasil or Amazil?), Eleanor, Emma, Everleaf (Basil Pesto Party), Devotion, Obsession, and Thunderstruck. I’m growing Amazel and Everleaf this year. No sign of mildew on Amazel. Everleaf, this year, at least, has it as bad as my standard varieties.

None of the resistant mentioned varieties are immune to basil downy mildew, just resistant. So it pays to also give the plants a lot of sunlight and good air circulation, and consider pitted plants, for their mobility.

And Some Entomo . . . No, Etymology

Fun herb fact: The word “herb” was borrowed from the old French word erbe, which is why we don’t — and the British didn’t, initially — pronounce the h. Scribes in the 15th century, influenced by their knowledge of Latin, started using the Latin word herba. But still, no one spoke the h. Fast forward to the mid-19th-century and, all of a sudden, dropping h’s became a marker of low social class among the Brits, so they dropped them.

Left to its own devices, a fig can grow into a tangled mess. In part, that’s because fig trees can’t decide if they want to be small trees, with single or a few trunks, or large shrubs, with sprouts and side branches popping out all over the place.

A major frustration in my greenhouse fig journey has been insects, both scale insects and mealybugs. These pests never attack my potted figs which summer outdoors and winter indoors in my barely heated basement. In the greenhouse the problem each year became more and more severe, eventually rendering many of the ripe fruits inedible.

Left to its own devices, a fig can grow into a tangled mess. In part, that’s because fig trees can’t decide if they want to be small trees, with single or a few trunks, or large shrubs, with sprouts and side branches popping out all over the place.

A major frustration in my greenhouse fig journey has been insects, both scale insects and mealybugs. These pests never attack my potted figs which summer outdoors and winter indoors in my barely heated basement. In the greenhouse the problem each year became more and more severe, eventually rendering many of the ripe fruits inedible. All that despite my attempts at control by going over plants with a toothbrush dipped in alcohol, oil sprays, and sticky barriers to keep ants, which “farm” these pests, from climbing up the trunks.

All that despite my attempts at control by going over plants with a toothbrush dipped in alcohol, oil sprays, and sticky barriers to keep ants, which “farm” these pests, from climbing up the trunks. Those seeds will drop and germinate in the cooler temperature a few weeks hence. But I need cilantro now.

With foresight, I could have collected and sown these seeds a few weeks ago. The plants would have bolted (put energy into flowers rather than leaves) rather quickly but repeated sowings would have kept me in fresh new plants.

Those seeds will drop and germinate in the cooler temperature a few weeks hence. But I need cilantro now.

With foresight, I could have collected and sown these seeds a few weeks ago. The plants would have bolted (put energy into flowers rather than leaves) rather quickly but repeated sowings would have kept me in fresh new plants. So I started the water sprays again, which have the potential problem of creating so much humidity and moisture that ripening figs rot. On the other hand, it might set back the scale, perhaps by knocking off ants, who “farm” scale. I also ordered a new predator, one for scale, Aphytis melinus.

So I started the water sprays again, which have the potential problem of creating so much humidity and moisture that ripening figs rot. On the other hand, it might set back the scale, perhaps by knocking off ants, who “farm” scale. I also ordered a new predator, one for scale, Aphytis melinus.

Birds also eat fruit for their juiciness, and the past weeks and weeks of abundant rainfall probably satisfied some of that need. The only other year I had plenty of mulberries — much more than this year — was a few years ago when 17-year cicadas descended upon here. All summer I awoke to their grating cacophony, but did feast on mulberries as birds feasted on the cicadas.

Birds also eat fruit for their juiciness, and the past weeks and weeks of abundant rainfall probably satisfied some of that need. The only other year I had plenty of mulberries — much more than this year — was a few years ago when 17-year cicadas descended upon here. All summer I awoke to their grating cacophony, but did feast on mulberries as birds feasted on the cicadas.

More than I have ever seen in the wild. (In Chanticleer Garden outside Philadelphia is a wet meadow planted thickly with cardinal flowers.)

More than I have ever seen in the wild. (In Chanticleer Garden outside Philadelphia is a wet meadow planted thickly with cardinal flowers.)

(Compost is all my vegetables get.) And perhaps focussing more on what food really tastes like. Does Sugarbuns supersweet really taste like corn. Or a candy bar?

(Compost is all my vegetables get.) And perhaps focussing more on what food really tastes like. Does Sugarbuns supersweet really taste like corn. Or a candy bar? The fittings for wending water through tubes around corners and up into pots are low pressure fittings; the pressure lowers water pressure to a mere 20 psi.

The fittings for wending water through tubes around corners and up into pots are low pressure fittings; the pressure lowers water pressure to a mere 20 psi. Part of the capillary mat dips into the reservoir of water, which gets sucked up into the mat and then sucked up into the potting soil through the drainage holes in each flat-bottomed plant pot.

Part of the capillary mat dips into the reservoir of water, which gets sucked up into the mat and then sucked up into the potting soil through the drainage holes in each flat-bottomed plant pot.

The endive seedlings will be ready to move out into the garden in 5 or 6 weeks. I’ve also sown more kale seeds to supplement the spring kale for harvest into and perhaps through (depending on the weather) winter.

The endive seedlings will be ready to move out into the garden in 5 or 6 weeks. I’ve also sown more kale seeds to supplement the spring kale for harvest into and perhaps through (depending on the weather) winter.

Once Earliglow stops bearing for the season, the bed will need renovation and, through the season, its runners pinched off weekly to keep each plant “spacey.”

Once Earliglow stops bearing for the season, the bed will need renovation and, through the season, its runners pinched off weekly to keep each plant “spacey.”

I’m banking, for instance, on the slightly warmer temperatures near the wall of my house to get my stewartia tree, which is borderline hardy here, through our winters. (It has.) And I expect spring to arrive early each year, with a colorful blaze of tulips, in the bed pressed up against the south side of my house. Proximity to paving also warms things up a bit.

I’m banking, for instance, on the slightly warmer temperatures near the wall of my house to get my stewartia tree, which is borderline hardy here, through our winters. (It has.) And I expect spring to arrive early each year, with a colorful blaze of tulips, in the bed pressed up against the south side of my house. Proximity to paving also warms things up a bit. By planting the coveted blue poppy in a bed on the east side of my house, I hoped to give the plant the summer coolness that it demands. (That east bed was still too sultry; the plants collapsed, dead.)

By planting the coveted blue poppy in a bed on the east side of my house, I hoped to give the plant the summer coolness that it demands. (That east bed was still too sultry; the plants collapsed, dead.)

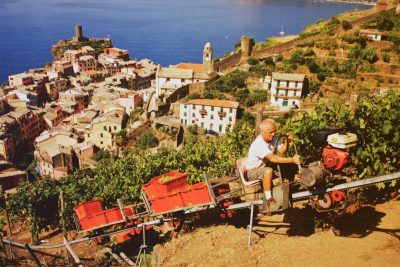

The cold air that settles here on clear spring nights increases the likelihood of late frosts and also causes moisture to condense on the plants, leaving them more susceptible to disease. Hence my envy for that sloping vineyard site.

The cold air that settles here on clear spring nights increases the likelihood of late frosts and also causes moisture to condense on the plants, leaving them more susceptible to disease. Hence my envy for that sloping vineyard site.

forsythia, mockorange, hydrangea, and any other informal shrub. This technique is known as rejuvenation pruning because, over time, the above ground portion of the shrub is annually rejuvenated. In the case of blueberry, the roots live unfettered year after year but the bush never sports stems more than 6 years old. A perennially youthful blueberry bush can go on like this, bearing well, for decades like this.

forsythia, mockorange, hydrangea, and any other informal shrub. This technique is known as rejuvenation pruning because, over time, the above ground portion of the shrub is annually rejuvenated. In the case of blueberry, the roots live unfettered year after year but the bush never sports stems more than 6 years old. A perennially youthful blueberry bush can go on like this, bearing well, for decades like this. , rose-of-sharon, climbing roses, and flowering quince. These shrubs are among those that perform well year after year on the same old, and always growing older, stems. They also grow few or no suckers each year. The upshot is that thesis shrubs are the easiest to prune: Don’t.

, rose-of-sharon, climbing roses, and flowering quince. These shrubs are among those that perform well year after year on the same old, and always growing older, stems. They also grow few or no suckers each year. The upshot is that thesis shrubs are the easiest to prune: Don’t.