In the Wild

Row, Row, Row My Boat, and Then!

Paddling down a creek — Black Creek in Ulster County, New York — yesterday evening, I was again awed at Mother Nature’s skillful hand with plants. The narrow channel through high grasses bordered along water’s edge was pretty enough. The visual transition from spiky grasses to the placid water surface was softened by pickerelweeds’ (Pontederia cordata) wider foliage up through which rose stalks of blue flowers. Where the channel broadened, flat, green pads of yellow water lotus (Nelumbo lutea) floated on the surface. Night’s approach closed the blossoms, held above the pads on half-foot high stalks, but the flowers’ buttery yellow petals still managed to peek out.

Soon I came upon the real show, as far as I was concerned: fire engine red blossoms of cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis). Coming upon this flower in the wild is startling. Such a red flower in such shade?

So many shade plants bear white flowers which, after all, are most easily seen in reduced light. Only twice before had I come upon cardinal flower in the wild, and both times the blooming plant was in deep, deep shade; it was a rare treat to see such a lively color in the shade.

Though the stream bank was not in deep shade, the cardinal flower was still a treat. And not just one cardinal flower but groups of them here and there along the way.  More than I have ever seen in the wild. (In Chanticleer Garden outside Philadelphia is a wet meadow planted thickly with cardinal flowers.)

More than I have ever seen in the wild. (In Chanticleer Garden outside Philadelphia is a wet meadow planted thickly with cardinal flowers.)

Nature’s Hand

Two other landscape vignettes come quickly to mind when I marvel at natural beauty.

The first are the rocky outcroppings in New Hampshire’s White Mountains; placement of these rocks always looks just right. In addition, the flat areas against the rocks and in rock crevices in which leaves have accumulated to rot down into a humus-y soil provide niches for plants. Among the low growing plants are lowbush blueberries and lingonberries.

Lingonberry in White Mountains

Good job at “edible landscaping” Ms. Nature!

The other vignette was (one of many) in the Adirondack Mountains. Picture a clump of trees and a large boulder. Now picture those trees on top of the boulder, their roots wrapping around and down the bare boulder until finally reaching the ground on which the boulder sat. A scene both pretty and amazing.

But My Fruits and Vegetables are Better(?)

Mother Nature might have it in the landscape design department; not when it comes to growing fruits and vegetables though. There may be some disagreement here: I contend that garden-grown stuff generally tastes better. And for a number of obvious reasons.

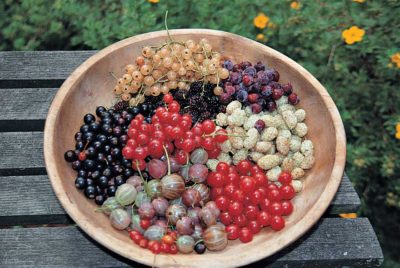

In the garden, most of what we grow are named varieties, derived from clones or strains that have been selected from among wild plants, or have been bred. Named varieties generally are less bitter, sweeter, and/or more tender. Perhaps also high-yielding and pest-resistant.

In some cases, “cultivated” plants offer too much of a good thing. Humans long sought to sink their teeth into the sweetest sweet corn, harvesting ears at their peak of perfection and then whisking them into already boiling water to quickly stop the enzymatic conversion of sugars to starches. In the 1950s, a “supersweet” gene was discovered that quadrupled the sugar content of sweet corn — too sweet for me and and lacking the richness of an old-fashioned sweet corn variety such as Golden Bantam.

A nutritional case can be made against cultivated varieties of plants. Studies by the US Department of Agriculture have shown modern fruits and vegetables to be lower in nutrients than those tested 50 or so years ago. Have we excessively mined our soils of minerals? No. Breeding for bulk, along with pushing plant growth along with plenty of water and nitrogen fertilizer, has diluted the goodness in plants.

In Eating on the Wild Side Jo Robinson contends that breeding for sweeter and less bitter plants inadvertently selects for plants lower in many nutrients and phytochemicals.

All this makes a good case for growing more “old-fashioned” varieties, such as heirloom tomatoes and paying closer attention to how plants are fed. (Compost is all my vegetables get.) And perhaps focussing more on what food really tastes like. Does Sugarbuns supersweet really taste like corn. Or a candy bar?

(Compost is all my vegetables get.) And perhaps focussing more on what food really tastes like. Does Sugarbuns supersweet really taste like corn. Or a candy bar?

And eat some wild things. Purslane is abundant and, to some (not me) tasty now. As is pigweed, despite its name, a delicious cooked “green.” I mix it in with kale and chard for a mix of cultivated and wild on the dinner plate.

If the area is wet, though, taking soil from paths is going to lower them, making them that much wetter.

If the area is wet, though, taking soil from paths is going to lower them, making them that much wetter. Paths get replenished with wood chips only if they start to get weedy or bare soil starts peeking through.

Paths get replenished with wood chips only if they start to get weedy or bare soil starts peeking through. Moss carpeting the soil beneath it and creeping up the trunk complete the picture. I’ve made and am making baby ficus into a bonsai.

Moss carpeting the soil beneath it and creeping up the trunk complete the picture. I’ve made and am making baby ficus into a bonsai. Clipping the leaves accomplishes two goals. First, plants lose water through their leaves so removing leaves reduces water loss (important in consideration of the next celebratory step).

Clipping the leaves accomplishes two goals. First, plants lose water through their leaves so removing leaves reduces water loss (important in consideration of the next celebratory step). Baby ficus gets all water and its nourishment from this amount of soil. Within 6 months or so, roots thoroughly fill the pot of soil and have extracted much of the nourishment contained within.

Baby ficus gets all water and its nourishment from this amount of soil. Within 6 months or so, roots thoroughly fill the pot of soil and have extracted much of the nourishment contained within. As far as science, I shorten stems where I want branching, usually just below the cut. Where I don’t want branching but want to decongest stems, I remove a stem or stems right to their base. I also remove any broken, dead, or crossing branches unless, of course, leaving them would be picturesque.

As far as science, I shorten stems where I want branching, usually just below the cut. Where I don’t want branching but want to decongest stems, I remove a stem or stems right to their base. I also remove any broken, dead, or crossing branches unless, of course, leaving them would be picturesque.

A few loops of string or thin wire can unobtrusively firm everything in place.

A few loops of string or thin wire can unobtrusively firm everything in place. Besides the obvious — pine cones — also consider the flattened silvery pods of silver dollar plant, the wiry ones of love-in-a-mist, and the shaggy manes of clematis. If yet more ornamentation is wanted, there’s always chains of cranberries or popcorn strung together.

Besides the obvious — pine cones — also consider the flattened silvery pods of silver dollar plant, the wiry ones of love-in-a-mist, and the shaggy manes of clematis. If yet more ornamentation is wanted, there’s always chains of cranberries or popcorn strung together.