THE SHOW GOES ON

Lesser Known

A whole slew of clear, sunny days and cool nights caused sugar maples to put on a particularly fiery show of yellow and orange leaves this fall. That’s mostly over now around here — but a number of other trees and shrubs, many not well known, are keeping my farmden and beyond colorful longer.

Little known, for instance is Persian ironwood (Parrotia persica). I planted it years ago as a shade tree. Big mistake! For shade, that is. It doesn’t grow very large and is more of a large, multistemmed shrub. I’m glad I planted it, though. The smooth, gray stems grow thick and often horizontally, then downward a little before heading skyward, sort of like a miniature beech.

But I’m writing about color, and Persian ironwood has it, the leaves emerging purplish in spring, turning a lustrous green in summer, then morphing into variable shades of yellow, orange and red in autumn.

But I’m writing about color, and Persian ironwood has it, the leaves emerging purplish in spring, turning a lustrous green in summer, then morphing into variable shades of yellow, orange and red in autumn.

Also not well known is Korean mountainash (also called Korean whitebeam, Sorbus alnifolia). It’s closely related to more familiar mountainashes except in a different subgenus, Aria, with simple, rather than compound, leaves. I first saw this tree one fall at the Scott Arboretum in Pennsylvania and, knowing the tiny fruits make a good nibble, ate some. And knowing a whole tree can be grown from a tiny seed, I saved some seeds for planting.

That was in 2006, and the tree is now about 20 feet tall and draped in rusty red leaves that are splashed with yellow. As with the sugar maples, the color is particularly good this year — and fruits, which I’ll be nibbling, are also particularly abundant. As an added plus, the tree, each spring, is draped in large clusters of foamy, white flowers.

Another rare bird is Japanese stewartia (Stewartia pseudocamellia) which I planted — was it for its bark, for its flowers, or was it for its autumn leaf color? All are outstanding. The bark exfoliates in the same way as does sycamore, leaving silvery gray and charcoal gray patches against a khaki background. Its cup-shaped, white flowers with yellow center are like camellias, a relative. Right now, the leaves are a warm terra cotta color shading, in parts, to yellow.

Stewartia

Fothergilla (Fothergilla gardeneii) is one more lesser known plant now aglow here. This small shrub’s leaves’ traffic-stopping, rich red color is heightened by occasional blushes of yellow and dark red. Back in spring, candles of fragrant, creamy white flowers perched atop the ends of stems.

Known for Their Fruits

Some plants that I grow for their fruits are also more than earning their keep with fall color.

Huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata) is among the best of these, and the color makes up for its relatively poor yield of fruit. The deep red leaves look pretty highlighted among the evergreen leaves of rhododendron, mountain laurel, and lingonberry in my “heather bed.” (All are in the Heather Family, Ericaceae.) Where the plants are really spectacular is in the Shawangunk Mountains that rise up just west of here. There, whole swaths of plants paint the forest understory red.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is another fruit plant here, this one with many tropical aspirations. Tropical aspirations? It’s the northernmost member of the mostly tropical Custard Apple family (Annonaceae); its fruit has taste and texture reminiscent of banana; the fruits hang in clusters like bananas; and its long, drooping leaves would be visually at home in tropical climes. Come fall, the plants shed those tropical aspirations as the leaves turn clear yellow, especially nice when backlit by sunlight.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is another fruit plant here, this one with many tropical aspirations. Tropical aspirations? It’s the northernmost member of the mostly tropical Custard Apple family (Annonaceae); its fruit has taste and texture reminiscent of banana; the fruits hang in clusters like bananas; and its long, drooping leaves would be visually at home in tropical climes. Come fall, the plants shed those tropical aspirations as the leaves turn clear yellow, especially nice when backlit by sunlight.

I often rave about blueberry for its ease of growth, its pretty, white flowers in spring, its long season of harvest, its health benefits, and of course, its delicious fruits. I’m sure I’ve also mentioned its fall color, to me one of the best of all plants, mostly crimson but depending on the variety and the season, also with some yellow.

(I delve into the planting and use of these and other ornamental fruit plants in my book Landscaping with Fruit.)

Look Down

Perhaps it was a couple of particularly cold nights, with temperatures dropping into the low 20s, that caused leaves to all of a sudden drop all at once from certain trees. At any rate, the beautiful carpets blanketing the ground beneath these trees have caught my eye.

Pawpaws, for one, the overlapping, large leaves thoroughly hiding the grass beneath them.

Even at their best, mulberries leaves are nothing to look at in fall (but the trees do have other ornamental attributes, so did make it into Landscaping with Fruit). This year, though, the green leaves that plopped onto the ground following the cold nights did catch my eye. Perhaps it was the low angle of the sun reflecting off them; perhaps it was their shine.

One tree whose leaves are perhaps at their best on the ground in ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba). This one is edible, allegedly delicious, but did not make it into my book. The edible part is the nut (seed) inside the fruit. The problem, for me, is that the fallen fruit smell like an open sewer. Really!

The way around this is to forgo the fruit by planting a male tree. The fan-shaped leaves of this living fossil, whose appearance dates back to the Early Jurassic, turn the clearest yellow imaginable in fall. They’re at their best when they drop, making the ground look as if a sunbeam had fallen from the sky.

I haven’t — yet? — grown ginkgo myself.

Scott Nearing was a professor of economics, a political activist, a pacifist, a vegetarian and an advocate of simple living. And a gardener. For many of these reasons, he was almost a cult figure back in the 1970s when I, a young man, visited him. He was then known mostly for his book Living the Good Life. I had read the book, and decided to drive 1,000 miles from Madison, Wisconsin to show up on his farm, unannounced, in Harborside, Maine.

Scott Nearing was a professor of economics, a political activist, a pacifist, a vegetarian and an advocate of simple living. And a gardener. For many of these reasons, he was almost a cult figure back in the 1970s when I, a young man, visited him. He was then known mostly for his book Living the Good Life. I had read the book, and decided to drive 1,000 miles from Madison, Wisconsin to show up on his farm, unannounced, in Harborside, Maine. For me, working my field in the quiet of early morning, with the sun low in the sky and grasses still moist from morning dew, is sheer pleasure. A morning dance.

For me, working my field in the quiet of early morning, with the sun low in the sky and grasses still moist from morning dew, is sheer pleasure. A morning dance.

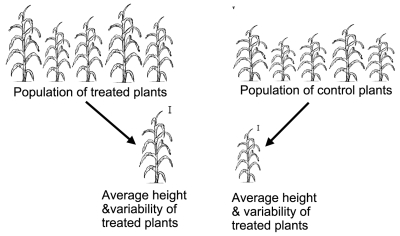

In practice, I mostly pay attention to rotation of plants most susceptible to diseases, which are cabbage and its kin (all in the Brassicaceae), cucumber and its kin (Cucurbitaceae), tomato and its kin (Solanaceae), beans and peas (Fabaceae), and corn (sweet or pop, in the Gramineae).

In practice, I mostly pay attention to rotation of plants most susceptible to diseases, which are cabbage and its kin (all in the Brassicaceae), cucumber and its kin (Cucurbitaceae), tomato and its kin (Solanaceae), beans and peas (Fabaceae), and corn (sweet or pop, in the Gramineae). Root, leafy, and fruiting vegetables have somewhat different nutrient needs, so in the ideal garden these crops are rotated to make best use of soil nutrients.

Root, leafy, and fruiting vegetables have somewhat different nutrient needs, so in the ideal garden these crops are rotated to make best use of soil nutrients. A few years ago they stopped bearing well, collapsing with yellowing foliage not long after they bore their first pods.

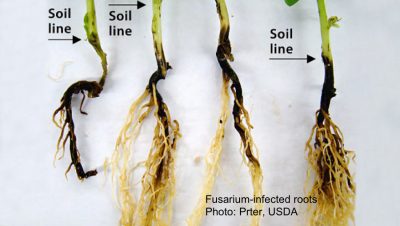

A few years ago they stopped bearing well, collapsing with yellowing foliage not long after they bore their first pods. Plants infected by aphanomyces have fewer branch roots and what roots there are lack the plump, white appearance of healthy roots.

Plants infected by aphanomyces have fewer branch roots and what roots there are lack the plump, white appearance of healthy roots.

My tea is nothing more than the liquid strained from compost soaked in water, then applied with a watering can at the base of the pea plants.

My tea is nothing more than the liquid strained from compost soaked in water, then applied with a watering can at the base of the pea plants.

And what about winter? A greenhouse full of salad and cooking greens solved that problem, in addition to providing figs in summer and early and late season cucumbers.

And what about winter? A greenhouse full of salad and cooking greens solved that problem, in addition to providing figs in summer and early and late season cucumbers.

Weeds have been removed from the paths and the beds, and spent plants have been cleared away. What remains of crops is a bed with some tall stalks of kale that were planted back in spring. Yet another bed is home to various varieties of lettuce interplanted with endive, all of which went in as transplants after an early crop of green beans had been cleared and the bed was weeded, then covered with an inch depth of compost. Also still lush green is a bed previously home to edamame, which was subsequently weeded, composted, and then seeded with turnips and winter radishes back in August.

Weeds have been removed from the paths and the beds, and spent plants have been cleared away. What remains of crops is a bed with some tall stalks of kale that were planted back in spring. Yet another bed is home to various varieties of lettuce interplanted with endive, all of which went in as transplants after an early crop of green beans had been cleared and the bed was weeded, then covered with an inch depth of compost. Also still lush green is a bed previously home to edamame, which was subsequently weeded, composted, and then seeded with turnips and winter radishes back in August.

Below ground, oat roots pull up nutrients that rain and snow might otherwise leach away into the groundwater.

Below ground, oat roots pull up nutrients that rain and snow might otherwise leach away into the groundwater.

Goldenrod gets the blame for its showy, yellow blossoms during this allergy season. But the true culprit is ragweed, which goes unnoticed because it bears only small, green flowers.

Goldenrod gets the blame for its showy, yellow blossoms during this allergy season. But the true culprit is ragweed, which goes unnoticed because it bears only small, green flowers.