OF COMPOST, MICROWAVES, AND BLUEBERRIES

/15 Comments/in Fruit, Soil/by Lee ReichManure Unnecessary

Manure or not, it’s compost time. I like to make enough compost through summer so that it can get cooking before autumn’s cold weather sets in. Come spring, I give the pile one turn and by the midsummer the black gold is ready to slather onto vegetable beds or beneath choice trees and shrubs.

I haven’t gotten around to getting some manure for awhile so I just went ahead this morning and started building a new pile without manure. It’s true: You do not need manure to make compost. Any pile of organic materials will decompose into compost given enough time.

My piles are a little more deliberate than mere heaps of organic materials. For one thing, everything goes into square bins each about 4′ on a side and built up, along with the materials within, Lincoln-log style from notched 1 x 6 manufactured wood decking. Another nice feature of this system is that the compost is easy to pitchfork out of the pile as sidewalls are removed with the lowering compost.

My main compost ingredient is hay that I scythe from an adjoining field. As this material is layered and watered into the bin it also gets sprinkled regularly with some soil and limestone. Soil adds some bulk to the finished material. The limestone adds alkalinity to offset the naturally increasing acidity of many soils here in the Northeast. Into the pile also goes any and all garden and kitchen refuse whenever available.

What manure adds to a compost pile is bedding, usually straw or wood shavings, and what comes out of the rear end of the animal. The latter is useful for providing nitrogen to balance out the high carbon content of older plant material in the compost, such as my hay.

But manure isn’t the only possible source of nitrogen. Young, green, lush plants are also high in nitrogen, as are kitchen trimmings, hair, and feathers. Soybean meal, or some other seed meal, is another convenient source.

Compost piles fed mostly kitchen trimmings or young plants benefit from high carbon materials. Otherwise, these piles become too aromatic, not positively.

As I wrote above, “Any pile of organic materials will decompose into compost given enough time.” Nitrogen speeds up decomposition of high carbon compost piles, enough to shoot temperatures in the innards of the pile to 150° or higher. All that heat isn’t absolutely necessary but does kill off most pests, including weed seeds, quicker than slow cooking compost piles.

Plus, it’s fun nurturing my compost pets, the microorganisms that enjoy life within a compost pile.

Novel Use for Microwave

I bought my first (and only) microwave oven a few years ago ($25 on craigslist) and have cooked up many batches of soil in it. You thought I was going to use it to cook food? Nah.

Usually, I don’t cook my potting soils, which I make by mixing equal parts sifted compost, garden soil, peat moss, and perlite, with a little soybean meal for some extra nitrogen. I avoid disease problems, such as damping off of seedlings, with careful watering and good light and air circulation rather than by sterilizing my potting soils.

Peat, perlite, soil, and compost

Recently, however, too many weeds have been sprouting in my potting soil. Because my compost generally gets hot enough to snuff out weed seeds and because peat and perlite are naturally weed-free, these ingredients aren’t causing the problem. Garden soil in the mix is the major source of weeds.

So I cook up batches of garden soil, using the hi setting of the microwave oven for 20 minutes. My goal is to get the temperature up to about 180 degrees F., which does NOT sterilize the soil, but does pasteurize it. Overheating soil leads to release of ammonia and manganese, either of which can be toxic to plants. Sterilizing it also would leave a clean slate on which any microorganism, good or bad, could have a field day. Pasteurizing the soil, rather than sterilizing it, leaves some good guys around to fend off nefarious invaders.

After the soil cools, I add it to the other ingredients, mix everything up thoroughly, and shake and rub it through ½ inch hardware cloth mounted in a frame of two-by-fours. This mix provides a good home for the roots of all my plants, everything from my lettuce seedlings to large potted fig trees.

Blueberry Webinar

Blueberries, as usual, are bearing heavily this year, with over 60 quarts already in the freezer and almost half that amount in our bellies. After years of growing this native fruit, it has never failed me, despite some seasons of too little rain, some of too much rain, late frost, or other traumas suffered by fruit crops generally.

All of which leads up to my invitation to you to come (virtually) to my upcoming Blueberry Workshop webinar. This webinar will cover everything from choosing plants to planting to the two important keys to success with blueberries, pests, harvest, and preservation. And, of course, there will be opportunity for questions. For more and updated information, keep and eye on www.leereich.com/workshops, the “workshops” page of my website.

DRIP WORK

/19 Comments/in Gardening, Soil/by Lee ReichMany Benefits of Drip

I’m a big fan of drip irrigation, an irrigation system by which water is frequently, but slowly, applied to the soil. It’s better for plants because soil moisture is replenished closer to the rate at which they drink it up. With a sprinkler, soil moisture levels vacillate between feast and famine.

Because of the efficient use of water, drip is also better for the environment, typically using 60 percent less water than sprinkling.

And drip is better for me — and you, if your garden or farmden is dripped. By pinpointing water to garden plants, large spaces between plants stay dry so there’s less weeds for us to pull. And best of all, with an inexpensive timer at the hose spigot, I turn on the system in April and then pretty much forget about watering until the end of the growing season.

Troubleshooting

Today I was reminded about the “pretty much” part of being able to forget about watering until the end of the season. My drip system is set up so that same main line that quenches plant thirst in my two vegetable gardens continues on to water about twenty potted plants. Or not!

I noticed yesterday that some of the potted plants were dry and assumed that the emitters bringing water to these pots were defective. Turns out that sometimes they dripped and sometimes they didn’t. Hmmm. I kept switching around and replacing the “defective” emitters and by the end of the day, for some reason, they were all working. Problem solved.

No! I have a hose connected near my well pump so that I can occasionally hand water some melons I’ve planted in a truckload of leaves a local landscaper provided me with last autumn. Water pressure was very low.

Long story short is that the seasonal line from the well to the pump has a short section of flexible, almost clear plastic tubing. Sun shining on the tubing grew a nice crop of algae within. I disconnected the tube and was able to remove an almost intact tube of algae that had been clogging the line. That was the culprit responsible for the capricious behavior of the drip system and the sluggish behavior of the hose for hand watering.

Thorough cleaning and reconnecting the tubing, wrapping it in aluminum foil to exclude light, priming the pump, and cleaning the sediment filter in the drip line had everything working waterly again. Geez, you gotta be a rocket science to keep things working smoothly. Well, not quite.

I’ve now marked my calendar to check the drip system every 3 weeks.

Some Attention Necessary

In addition to checking periodically to make sure that the water flows unobstructed, my watering system — any drip system — requires other regular attention, including a small amount of hand watering. The reason has to do with the shape of the wetting front drip presents in the soil. As a drip of water enters the ground, gravity pulls water downward at the same time that capillary action is pulling the water horizontally. Down in the ground, that wetting front is shaped like an ice cream cone, at first widening with depth and then narrowing to a point.

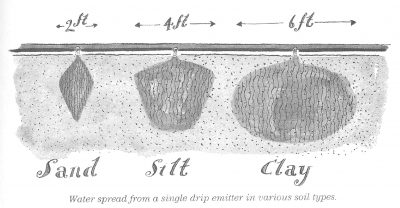

The width of the cone depends on soil porosity. Clay soils have small particles with commensurately small pores (illustration from my book Weedless Gardening).

Those small pores exert a strong capillary pull so the ice cream cone spreads wide, as much a six feet at its widest down from each point source of water. At the other extreme is a sandy soil, whose large particles have large spaces between them and comparatively little capillary pull; the result is a slender ice cream cone, spreading no more that a couple of feet wide.

A drip system is a series of emitters, so the wetting fronts can merge together at their widest points presenting a wetting front that in soil cross section looks like waves below ground, with peaks at ground level at each emitter. (This illustration is also from Weedless Gardening.)

Distance between peaks depends on the spacing of drip emitters. Depth of the wave troughs between the peaks depends on the soil texture and emitter spacing. A soil rich in clay with close emitter spacing would be wet at the peaks, with the “waves” relatively close to the ground surface between the peaks.

Between emitter peaks, the ground is dry near the surface. Plant a seed there and, in the absence of rain, the seed will just sit. Tuck a transplant into the soil there and, in the absence of rain, it will dry out and die. Hand watering gets that seed or transplant’s roots growing; once the roots reach down far enough to tap into the wetting front, they’re on their own.

To avoid hand watering I sometimes move the drip line right over the row where I planted seeds or right along the row where I set transplants. After a few days or once seeds sprout, I move the drip line back to its rightful position which, along with one other line, is about 9 inches in from each of the outer edges of my 3 foot wide vegetable beds.

Only one more maintenance item for my drip system. If it has rained cats and dogs, that is, more than 1 inch, as measured in a rain gauge, I might turn off the drip system temporarily. Then — and this is very important — I’ll stick a Post-It note on which is written “Drip” to my bathroom mirror as a reminder to turn the drip system back on in due time. Drip irrigation is low maintenance, but not no maintenance.

ENTERING THE TWILIGHT ZONE

/13 Comments/in Gardening, Planning, Vegetables/by Lee ReichBigger Garden, Same Size

Over the years I’ve greatly expanded my vegetable garden, for bigger harvests, without making it any bigger. How? By what I have called (in my book Weedless Gardening) multidimensional gardening.

I thought about this today as I looked upon a bed from which I had pulled snow peas and had just planted cauliflower, cabbage, and lettuce. Let’s compare this bed with the more traditional planting of single rows of plants, each row separated by wide spaces for walking in for hoeing weeds, harvesting, and other activities. No foot ever sets foot in my beds, which are 3 feet wide. Rather than the traditional one dimensional planting, I add a dimension — width — by planting 3 rows up that bed. Or more, if I’m planting smaller plant such as carrots or onions.

Let’s backtrack in time to when the bed was home to peas. Oregon Sugar Pod peas grow about 3 feet tall, so after planting them in early April, I made accommodations for them to utilize a third dimension in that bed, up. A three foot high, temporary, chicken wire fence allowed them to grow up, flanked on one side by a row of radishes and on the other side by a row of lettuce.

60 pounds of onions in 33 square feet!

There you have it, 3 dimensions. The bed length. The bed width, only three feet wide, with three or more rows down its length. And up.

A Fourth Dimension

Three dimensions isn’t the end of the story for multidimensional gardening. Time is another dimension. Neither peas nor radishes nor lettuce, occupy any bed for a whole season. Peas peter out in hot weather which, along with longer days, tells radish and lettuce plants that it’s time to go to seed. Those conditions tell me that radish roots are getting pithy and lettuce gets bitter, so out they go.

In my planting of cabbage, cauliflower, and lettuce, closer planting is possible because it allows room for longer maturing plants to expand as quicker maturing plants get harvested and out of the way. The middle row of the bed is planted to Charming Snow cauliflower, which will be ready for harvest around the first half of September. I can’t dawdle with that harvest because, left too long, cauliflower curds become loose and quality plummets.

I’ve planted Early Jersey Wakefield cabbage — an heirloom variety noted for its flavor — in a row eight inches away from the row of cauliflowers. The plants in the cabbage row are staggered with those in the cauliflower row, putting a little more space between plants from one row to the other. Early Jersey Wakefield will mature towards the end of September; no need to run out and harvest them all once they’re ready. In cool weather, the heads stay tasty and solid right out in the garden.

The row of Bartolo cabbage — a good storage variety — flanks the cauliflower on the other side of the bed. Bartolo requires 115 days to maturity.

Between each of the cabbage plants I’ve transplanted one or two lettuce seedlings. They’ll be ready for harvest and starting to get out of the way within a couple of weeks.

Mixing and Matching

How long a vegetable takes to mature, what kind of weather it likes, and the length of the growing season all need to be considered in order to make best use of four dimensions in the vegetable garden. Doing so, it’s often possible to grow three different crops in the same bed in a single season.

Here’s a table I made up listing some combinations that have worked well in my planting beds according to preferred temperature (cool or warm) and time needed until harvest (short, medium, or long season). That’s for here in New York’s Hudson Valley, with a growing season of about 170 days.

For example, looking at the first group, a tomato bed could start with lettuce, which will be out of the way by the time tomato transplants have spread to need the space. An example from the second group would be a bed with an early planting of turnips followed by a planting of okra followed by a planting of spinach.

A big advantage of these mixed plantings is that they present less of a visual or olfactory target for pests to hone in on, and they cover the ground enough to shade it to limit weed growth.

Lettuce and cucumbers

Carrots and lettuce following early corn

And Finally, the Twilight Zone, But Not For Now

Is it possible to find yet another dimension in the vegetable garden, a dimension beyond space and time? The Twilight Zone. Sort of. This fifth dimension is made up of a few tricks designed to find time where it is not, tricks meant to add days or weeks to the beginning and/or end of the growing season. But mid-July isn’t the time to detail ways of adding this dimension.

Trying to fill every available niche of physical space and time in the vegetable garden is like doing a four- (or is it five-?) dimensional jigsaw puzzle. Assembling this puzzle can sometimes bring on as much frustration as doing a real jigsaw puzzle. When I began gardening, I would sometimes get overwrought trying to integrate every multidimensional “puzzle” piece into every square inch of garden. Then I learned: When in doubt, just go ahead and plant.