BLUEBERRY GROWING WEBINAR REDUX

/2 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee Reich•For anyone who missed my recent 90 minute webinar on Growing Blueberries, the webinar has been recorded and is available soon for a limited time period on-demand for $35. The webinar covers everything from plant selection to planting to maintenance to pests to harvest and preservation. Including, of course, the all important getting the soil right and dealing with birds.

•After this webinar, you will be really good at growing blueberries!

•Contact me before 9 am EST August 20, 2020 if you’d like to view the webinar.

SOMETHING A LITTLE DIFFERENT, IN FRUIT

/13 Comments/in Fruit/by Lee Reich(Adapted from my book Uncommon Fruits for Every Garden, now out of print but very soon available as online version. Stay tuned. Information is also available in my books Grow Fruit Naturally and Landscaping with Fruit, available from my website and the usual sources.)

I always know when my hardy kiwifruits are ripe because my dogs and ducks start grubbing around beneath the vines for drops. The fruits, for those unfamiliar with them, are similar to the fuzzy kiwifruits (Actinidia deliciosa) of our markets, only much better for a number of reasons.

Obviously, from the name, hardiness is one reason. Hardy kiwifruits will laugh off cold below even minus twenty-five degrees Fahrenheit, while market kiwis are injured below zero degrees Fahrenheit.

Another difference is in the fruit itself. Hardy kiwifruits are grape-size, with smooth, edible skins. Pop them into you mouth just as with grapes. Within the skin, hardy kiwifruits look just like market kiwis, in miniature. The flavor of hardy kiwifruits, though, is far superior to that of the fuzzies, sweeter and with more aroma.

Okay, I have to qualify that last statement because there are actually two different species of fuzzy kiwifruits. A. chinensis, rarely seen for sale outside China, is relatively large (though usually not as large as A. deliciosa) with skin covered by only a peach-like fuzz. The flesh color ranges from green to yellow, on some plants even red, in the center. The flavor is very sweet and aromatic, smooth and somewhat tropical, reminiscent of muskmelon, tangerine, or strawberry. In all honesty, this kiwifruit has the best flavor of all — but it’s even less cold hardy than the more common fuzzy, market kiwifruit. If winter temperatures here were mild enough for me to grow A. chinensis, I would.

Two Species, One Flavor

Hardy kiwifruits also come in two species: A. kolomikta and A. arguta. But not two flavors; they taste pretty much the same.

Both are ornamental vines, so much so that they were originally introduced into this country from Asia over 100 years ago strictly for their beauty, their innocuous fruits overlooked. How many visitors pass beneath the many handsome vines planted early in the twentieth century on public and private estates, unaware of the delectable fruits also hidden beneath the foliage?

For most kiwifruits, male and female flowers are borne on separate plants. Only the females bear fruit, but males are needed for pollen to get that fruit to form. (Just like humans and most animals, the “fruit” in animals being the ovary responding to fertilization.) One male (kiwi plant) can sire up to about eight females.

The two species of hardy kiwifruits do have their differences. The one that’s ripe for me now is A. kolomikta, which I choose to call the super-hardy kiwifruit because it’s cold-hardy to below minus forty degrees F. (For a pleasant dance of your tongue, sound out and speak the species name slowly.) Kolomikta is the more strikingly ornamental of the two because of the pink and silvery variegation of its leaves.  This species is also relatively sedate in growth, so is easier to manage. One problem with this fruit, which my ducks and dogs consider a plus, is that it drops when it is ripe, perhaps because it’s ripening so quickly during hot days of summer.

This species is also relatively sedate in growth, so is easier to manage. One problem with this fruit, which my ducks and dogs consider a plus, is that it drops when it is ripe, perhaps because it’s ripening so quickly during hot days of summer.

The other species, A. arguta, is more sedately ornamental, with apple-green leaves attached to the vines on reddish leaf stalks. Fruits of this species, depending on the variety, start ripening in the middle of September, and they stay firmly attached. One problem with A. arguta, mostly for casual growers, is that it’s much less sedate in growth. My vines send out a number of 10 foot long canes every year.

Must You Prune?

Pruning keeps either species productive and within bounds. Containing the plant is especially important with A. arguta. A number of years ago, I gifted two plants to a friend. He planted them at the base of a sturdy arbor that was attached to his front door. I’m not sure he ever pruned the plant, and 15 years later the arbor was on the ground.

Still, either species grows best trained to some sort of structure. Mine, which are grown mostly for fruit, are trained on a series of T-shaped posts fifteen feet apart and joined at their cross-members by five equally spaced wires. Each plant’s strongest shoot has been trained to become a trunk that reaches the center wire, then bifurcates into two permanent arms, called cordons, running in opposite directions along the center wire.

Each plant’s strongest shoot has been trained to become a trunk that reaches the center wire, then bifurcates into two permanent arms, called cordons, running in opposite directions along the center wire.

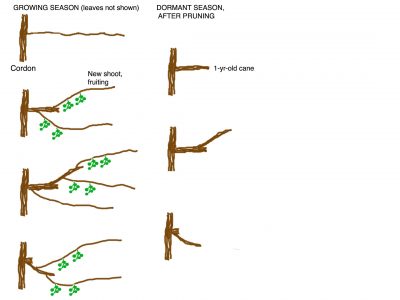

Fruiting canes grow off perpendicularly to the center wire and drape over the outside wires. Flowers and, hence, fruits are borne only toward the bases of shoots of the current season that grow from the previous year’s canes, very similarly to grape vines.

Annual winter pruning entails, first, pruning off any new shoots forming anywhere along or at the base of the trunk, and shortening cordons once they have reached full length. Fruiting arms give rise to laterals that fruit at their bases; during each dormant season, cut these laterals back to about eighteen inches in length. Remaining buds on the laterals will grow into shoots that fruit at their bases the following summer. The winter after they have fruited, these shoots correspondingly should be shortened to about eighteen inches, but leave only one of these. When a fruiting arm with its lateral, sublateral, and subsublateral shoots is two or three years old, it’s cut away to make room for a new fruiting arm.

With all this said, the vines do fruit with no more pruning than a yearly, undisciplined whacking away aimed at keeping them in bounds. Such was the objective in pruning those hardy kiwifruits planted as ornamentals on old estates. These vines happily and haphazardly clothe pergolas with their small, green fruits hanging—not always easily accessible or in prodigious quantity—beneath the leaves.

Note to plant nativists: I am aware that Actinidia species are considered to be non-native invasives in many areas. I’ve grown and watched this plant for decades and have never found it growing anywhere but where I planted it. As far as I can tell, the only way this plant can spread would be for it to be planted near enough to tree stands to give the vine leg up and then to be totally neglected. I have never seen a self-sown seedling pop up anywhere.

FINAL REMINDER FOR BLUEBERRY GROWING WORKSHOP WEBINAR ON AUG. 12, 2020, FROM 7-8:30 PM

/2 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichFinal reminder for my zoom Blueberry Growing Workshop/Webinar on August 12, 2020 from 7-8:30 pm EST. I’ll cover everything from planting right through harvest and preservation. If you’re new to growing blueberries, you’ll learn how to grow this fruit successfully. If you already grow blueberries, you’ll be able to grow them better. If you’re an expert on growing blueberries, you don’t need this workshop/webinar. Registration ($35) at https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_NSTrunuTRkOcRfS-frQuYg. For more information, go to https://leereich.com/workshops.