This Bud’s for You

Swelling Buds

What an exciting time of year! After a spate of 50 plus degree temperatures, lawn grass — bare now although it could be buried a foot deep in snow by the time you read this — has turned a slightly more vibrant shade of green. Like a developing photographic film (remember film?), the balsam fir, arborvitae, and hemlock trees I’m looking at outside my window, have also greened up a bit more.

Going outside to peer more closely at trees and shrubs reveals the slightest swelling of their buds. Earlier in winter, no amount of warmth could have caused this. As a cold weather survival mechanism, hardy trees and shrubs are “smart” enough to know to stay dormant until warm weather signals that it’s safe for tender young sprouts and flowers to emerge.

These plants stay asleep until they’ve experienced a certain number of hours of cool temperatures, the amount varying with both the kind and variety of plant.

Once that cold “bank” has been filled, the plants merely respond to warming temperatures. Which, for many plants, is now.

Physiology aside, the buds provide an interesting winter diversion; look at their sizes, their shapes, their colors, and textures. (Admittedly, their interest would pale in the landscape exploding into flowers and leaves, when the buds anyway mostly disappear into flowers or leaves until later in summer when new ones re-form.)

More than just interest, buds are useful. Buds can be used to identify the kind of plant as well as whether flower buds are in the offing. Or perhaps that flower buds were in the offing but were damaged by winter cold.

Info from Buds

The first bit of information I glean from winter buds is plant identification. To begin, how are the buds arranged along the stem? Buds directly opposite each other, which is relatively rare for local trees, narrows the choice down to maple, ash, dogwood, and horse chestnut, or, as some people remember it, MAD Horse.

L to R: peach, pawpaw, fantail willow, viburnum, dogwood

Of course, once I identify a tree as, for example, a maple, I have to look for other details, such as the bark, to tell if it is a red, sugar, silver, or Norway maple.

(A few less common trees also have opposite leaves, including katsura and paulownia, both non-native, and viburnums, some of which are native. Most shrubs have opposite leaves.)

Buds that are not opposite each other along a stem might be alternating along the stem, they might be whorled, or they might be almost, but not quite opposite, presenting a much wider field of plants from which to choose.

Then it’s time for a closer look at the buds themselves. Some plants—viburnums, for example—have naked buds, enveloped only by the first pair of (small) leaves, rather than the scaly covering protecting the buds of most other plants. Buds of plants such as maples have buds enclosed in scales that overlap like roof shingles. Or two or three scales might enclose a bud without any overlap, as they do on tuliptree.

Mature plants have two kinds of buds. Those that are longer and thinner will expand into shoots. Flower buds are usually fatter and rounder. I note how dogwood flower buds stand proud of the stems like buttons atop stalks — very decorative if you take the time to have a look. I take a look at a peach branch with its compound bud: a single, slim stem bud in escort between two fat flower buds.

Peach buds

Apple and crabapple flower buds occur mostly at the ends of stubby stems, called spurs, that elongate only a half an inch or so yearly. Pawpaws fruit buds are fat and round with a brown, velour, covering.

Practicalities aside, buds can predict what kind of flower show or fruit crop to expect, barring interference from late frosts, insects, diseases, birds, or squirrels. If peach fruit buds just sit in place rather than fattening as winter draws to a close, I’ll know that the night back in January when temperatures plummeted to minus 18 degrees Fahrenheit did them in, or at least some of them.

More Winter Details

Back to winter plant identification and entertainment. Looking more carefully at these leafless plants promotes familiarity. Notice the intricacies of their various barks; shagboark hickory, sugar maple, persimmon, white birch, and, my favorite, hackberry,

Hackberry bark

are very characteristic. Note twigs’ color, presence of ridges or lenticels (corky pores), even their taste or aroma. The aromas of yellow birch (wintergreen aroma), sassafras, and black cherry (almond) practically shout out their identification.

Moss carpeting the soil beneath it and creeping up the trunk complete the picture. I’ve made and am making baby ficus into a bonsai.

Moss carpeting the soil beneath it and creeping up the trunk complete the picture. I’ve made and am making baby ficus into a bonsai. Clipping the leaves accomplishes two goals. First, plants lose water through their leaves so removing leaves reduces water loss (important in consideration of the next celebratory step).

Clipping the leaves accomplishes two goals. First, plants lose water through their leaves so removing leaves reduces water loss (important in consideration of the next celebratory step). Baby ficus gets all water and its nourishment from this amount of soil. Within 6 months or so, roots thoroughly fill the pot of soil and have extracted much of the nourishment contained within.

Baby ficus gets all water and its nourishment from this amount of soil. Within 6 months or so, roots thoroughly fill the pot of soil and have extracted much of the nourishment contained within. As far as science, I shorten stems where I want branching, usually just below the cut. Where I don’t want branching but want to decongest stems, I remove a stem or stems right to their base. I also remove any broken, dead, or crossing branches unless, of course, leaving them would be picturesque.

As far as science, I shorten stems where I want branching, usually just below the cut. Where I don’t want branching but want to decongest stems, I remove a stem or stems right to their base. I also remove any broken, dead, or crossing branches unless, of course, leaving them would be picturesque.

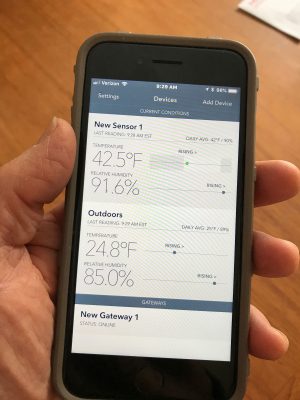

The Gateway connects via wi-fi to put the temperature and humidity information on the web and then on to my smartphone. From anywhere that I have cell service.

The Gateway connects via wi-fi to put the temperature and humidity information on the web and then on to my smartphone. From anywhere that I have cell service.  Just how much cold kills these blossoms depends on the kind of fruit and the stage of blossoming. For instance, when apricot flower buds have just begun to swell and separate, they’ll laugh off cold down to zero degrees F. Once the petals begin to spread, the buds are killed at 19°F. When petals fall, 24° is lethal.

Just how much cold kills these blossoms depends on the kind of fruit and the stage of blossoming. For instance, when apricot flower buds have just begun to swell and separate, they’ll laugh off cold down to zero degrees F. Once the petals begin to spread, the buds are killed at 19°F. When petals fall, 24° is lethal.

Though not related to clover, oxalis (Oxalis deppei, sometimes called the shamrock plant) leaves are dead ringers for clover leaves — except that all oxalis leaves have four leaflets. And better still, oxalis can be grown as a houseplant, affording you “four-leaf” clovers for year-round proclamations of affection.

Though not related to clover, oxalis (Oxalis deppei, sometimes called the shamrock plant) leaves are dead ringers for clover leaves — except that all oxalis leaves have four leaflets. And better still, oxalis can be grown as a houseplant, affording you “four-leaf” clovers for year-round proclamations of affection. The plant spends summers outdoors in semi-shade near the north wall of my house, and winters indoors on a sunny windowsill. I water it perhaps twice a week, unless I forget.

The plant spends summers outdoors in semi-shade near the north wall of my house, and winters indoors on a sunny windowsill. I water it perhaps twice a week, unless I forget. This orchid is Dendrobium kingianum, which does go under the more user-friendly common name of pink rock orchid. I have also gotten this one to flower — but not every year.

This orchid is Dendrobium kingianum, which does go under the more user-friendly common name of pink rock orchid. I have also gotten this one to flower — but not every year.

The sweet, resiny aroma is retained in air-dried plants for years. I keep a clump hanging upside down near my front door so that the aroma can waft into the air when the door is opened or someone brushes past.

The sweet, resiny aroma is retained in air-dried plants for years. I keep a clump hanging upside down near my front door so that the aroma can waft into the air when the door is opened or someone brushes past. And, like the tropical species, flowers are followed by egg-shaped fruits filled with air and seeds around which clings a delectable gelatinous coating. You know the flavor if you’ve ever tasted Hawaiian punch.

And, like the tropical species, flowers are followed by egg-shaped fruits filled with air and seeds around which clings a delectable gelatinous coating. You know the flavor if you’ve ever tasted Hawaiian punch. It’s peak of popularity was in the Middle Ages. And though popular, it was made fun of for it’s appearance; Chaucer called it the “open-arse” fruit.

It’s peak of popularity was in the Middle Ages. And though popular, it was made fun of for it’s appearance; Chaucer called it the “open-arse” fruit.

Mostly I grow it for the novelty of an outdoor orange tree, for the sweetly fragrant blossoms, and for the decorative, green, swirling, recurved spiny stems.

Mostly I grow it for the novelty of an outdoor orange tree, for the sweetly fragrant blossoms, and for the decorative, green, swirling, recurved spiny stems.