Immigrants Welcomed

Sad to See This One Leave, ‘Til Next Year

“So sad,” to quote our current president (not a president known, so far at least, for his eloquence). But I’m not sliding over into political commentary. I use to that pithy quote in reference to the fleeting glory of Rose d’Ipsahan.

A little background: Rose d’Ipsahan was given to me many years ago by a local herbalist under the name of Rose de Rescht, which it soon became evident it was not.  Descriptions of Rose de Rescht tell how it blossoms repeatedly through the season; not my rose. I finally honed down my rose’s identity from among the choices suggested by a number of rose experts based on photos and descriptions I had sent them.

Descriptions of Rose de Rescht tell how it blossoms repeatedly through the season; not my rose. I finally honed down my rose’s identity from among the choices suggested by a number of rose experts based on photos and descriptions I had sent them.

Under any name, Rose d’Ipsahan would be my favorite rose. Without any sort of protection, it’s never suffered any damage from winter cold. Insect and disease pests do it little or no harm. And rather than intimidating thorns, the stems are covered by more user-friendly prickles.

The best part of Rose d’Ipsahan is its blossoms, a loosely packed head of soft, pink petals that are attractive from the time the opening bud shows its first hint of pink until the head fully expands.  And the fragrance! Intense, and my favorite of all roses. Rose d’Ipsahan is a variety of Damask rose and has the classic fragrance of that category of rose.

And the fragrance! Intense, and my favorite of all roses. Rose d’Ipsahan is a variety of Damask rose and has the classic fragrance of that category of rose.

This rose was discovered in a garden in the ancient city of Esphahan (sometimes written as Ispahan, Sepahan, Esfahan or Hispahan) in Iran, making its way to Europe from Persia sometime in the early 19th century. Interesting that a rose claiming as home a part of the world with very hot summers, mild winters, and a year ‘round very dry climate does so well in my garden. And elsewhere; this is a cosmopolitan plant.

Why, the “So sad?” Because Rose d’Ipsahan blossoms only once a season. Then again, it does have a relatively long season — for a Damask rose. I’m thinking of making some new plants to plant near the east or north wall of my home where spring’s later arrival would delay the onset — and finish — of blossoming a few days after my plants in the sun. Rose d’Ipsahan also tolerates some shade.

A Wild Italian

Another immigrant in my garden is arugula. Not your run-of-the-mill arugula (Eruca sativa), but a different species, this one usually known as Italian or wild arugula (Eruca selvatica). Italian arugula has a peppery flavor similar to common arugula, to me a little less sharp.

Italian arugula has it over common arugula in two ways. First of all,I think it’s prettier, with deeply lobed rather than mostly rounded leaves.  More important, Italian arugula tolerates heat better. As my rows of common arugula are sending up seed stalks, the Italian arugula just keeps pumping out new leaves.

More important, Italian arugula tolerates heat better. As my rows of common arugula are sending up seed stalks, the Italian arugula just keeps pumping out new leaves.

The native home of arugulas, common and Italian, is the Mediterranean, where their flavors have been enjoyed since Roman times. Perhaps more than just for their flavor. In his poem Moretum, Virgil has the line “et Venerem revocans eruca morantem“ which translates to “and the rocket, which revives drowsy Venus’ [sexual desire].” Perhaps that’s why it was forbidden to grow arugula in monastery gardens in the Middle Ages.

It’s also been suggested that the reason arugula is often mixed with lettuce in a salad is to counteract arugula’s effect; lettuce contains the chemical lactucarium, a non-narcotic sedative and analgesic, structurally similar to opium. Lactucarium isn’t nearly as strong as opium, to say the least, because studies have shown none of the alleged effects from “lettuce opium,’ as the lettuce compound has been called. (I didn’t come across any studies confirming or denying the effects of arugula beyond good taste.)

Glad to Have These Immigrants

So there you have it, two immigrant plants well worth growing. I’m glad I welcomed them into my garden, and suggest you do so also.

But if I want some garlic flavor in spring, I can pull stalks out of the ground, peel off the outer covered of leaf sheath, and chop up the ivory white lower portion for use. Many I just pull out and toss into the compost pile; the garlic is getting weedy.

But if I want some garlic flavor in spring, I can pull stalks out of the ground, peel off the outer covered of leaf sheath, and chop up the ivory white lower portion for use. Many I just pull out and toss into the compost pile; the garlic is getting weedy.

If spreading mulch is delayed until the soil turns dry, all the more water will be required to give the soil below a good drenching.

If spreading mulch is delayed until the soil turns dry, all the more water will be required to give the soil below a good drenching.

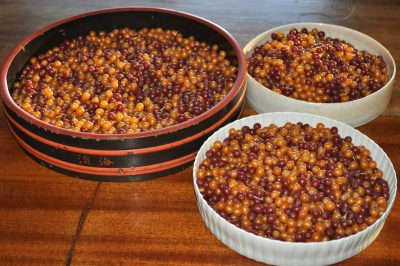

The plants were autumn olives (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrubs whose fine qualities I’m reluctant to mention for fear of eliciting scorn from you knowledgable readers.

The plants were autumn olives (Elaeagnus umbellata), shrubs whose fine qualities I’m reluctant to mention for fear of eliciting scorn from you knowledgable readers. Those fruits are very puckery until a little after they turn red, but then become quite delicious, and healthful.

Those fruits are very puckery until a little after they turn red, but then become quite delicious, and healthful.

If the area is wet, though, taking soil from paths is going to lower them, making them that much wetter.

If the area is wet, though, taking soil from paths is going to lower them, making them that much wetter. Paths get replenished with wood chips only if they start to get weedy or bare soil starts peeking through.

Paths get replenished with wood chips only if they start to get weedy or bare soil starts peeking through.