Fresh Watermelon, and More, with Help from Ethylene

Could I possibly be the best gardener west of the Hudson River? Perhaps. As evidence: On November 1st, here in Zone 5 of New York’s Hudson River Valley, where temperatures already have plummeted more than once to 25°F, I was able to harvest a fresh, dead-ripe watermelon. Not from a greenhouse, not from a hoop house, not even from a plastic covered tunnel. Watermelon, a crop sensitive to frost and thriving best in summer’s sun and searing heat.

Okay, perhaps I can’t assume all that much responsibility for the melon. Let me explain . . .

Every fall, I have a landscaper dump a whole truckload of leaves vacuumed up from various properties at my holding area for such things. Rain and snow drench the pile in the coming months, starting it on the road to decomposition. When sufficiently warm weather has decided to stay in spring, I scoop out a few holes in the pile, fill them with compost, then tuck in watermelon transplants.

Last fall’s pile yielded well from summer until early fall this year, at which time I gathered up remaining melons for eating or, if unripe, for composting along with the vines. The tractor, with its bucket, was able to move and compact the now dense pile to make way for this year’s crop of leaves.

Ben & Jeremy show off the November watermelon.

Now we’re up to November 1st, time to spread the leaf mold before it freezes — a big job that necessitated enlisting the help of my neighbors Jeremy and Ben. We were loading and hauling and loading and hauling, forking deeper and deeper into the bowels of the pile, when Jeremy yelled that he’d just speared a watermelon I had overlooked when cleaning up. I cleaned it off and sliced it open. It proved to be a ripe watermelon. The taste? “Awesome,” to quote Jeremy.

The Watermelon Mystery

Okay, I admit to not being able to claim too much credit for the ripe watermelon. How did it get there? Was it ripe and overlooked, then buried and preserved in the warm bowels of the leaf mold pile? Was it unripe when buried, then subsequently ripened? Probably not. No leaves were poking out of the pile, capturing the sun’s albeit weak rays for photosynthesis to make the sugars needed for ripening. A couple of nights of 25°F would have done in the leaves anyway.

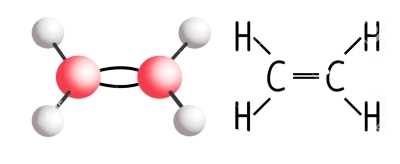

Some fruits can actually ripen after harvest. These include apples, pears, bananas, avocados, and other so-called climacteric fruits. Just before ripening, respiration of climacteric fruits dramatically increases along with a burst in production of the plant hormone ethylene. Through a feedback mechanism, ethylene stimulates more respiration which in turn stimulates even more ethylene production and even quicker ripening. Hence, enclosing bananas in a bag stimulates ripening, and why one rotten apple — injury, whether mechanical or from pests, also elicits an ethylene response — can indeed “spoil the barrel.”

This burst in ethylene production occurs even after climacteric fruits have been harvested, as long as they were sufficiently mature at the time. You can’t pick a golfball-sized green apple and expect it to ripen off the plant.

Non-climacteric fruits lack that pre-ripening spike in respiration and ethylene production, and do not ripen after harvest. Or so the thinking, based on early experiments, went. According to more recent research, fruits show various degrees of ethylene production. Watermelon is not a climacteric fruit, but at a certain point the white flesh within does release a burst of ethylene some time after which it morphs from bland and unripe to sweet, red, and ripe. But that won’t happen off the vine.

(“Ripe” is open to some debate. Peach, for instance, is a climacteric fruit that, if picked sufficiently mature but underripe, will soften and become more edible. But it won’t develop the aromatics of a tree-ripened fruit or, until rotting changes starches to sugars, become at all sweeter after picking. I don’t call that “ripe.”)

So my watermelon must have been overlooked and ripe and evidently kept perfectly well in the moist warmth of the leaf pile.

Deb & Ethylene Take Credit for the Peppers

Ethylene, and not me, is going to take credit for the fresh, sweet red peppers in today’s salad. Peppers are a climacteric fruit. Green peppers are unripe peppers, but if the fruits have just a hint of red on them, they can ripen even after harvest to full red (or yellow, orange, or purple, depending on the variety of pepper) color and, at least to my taste buds, flavor.

Still eating fresh, red, ripe sweet, juicy, delicious peppers.

Skill is needed to ripen peppers off the plant. Cool, but not too cool, temperatures hold the fruits for storage and warmer temperatures then speed ripening. Just the right amount of humidity is also needed to, on the one hand, avoid drying, or, on the other hand, rotting. My wife, Deb, rather than I, plies these skills, so should probably get credit for the ripe, red peppers.

This season has been the best pepper season ever, both in quantity and in quality. King of the North peppers, large and blocky, with thick, juicy walls, now ripening in a basket taste as bland now as they did all summer. I won’t grow them again. In contrast, Carmen, Sweet Italia, and (slightly hot) Pepperocini peppers, also ripening in that basket, taste as good now as their siblings did snapped from plants basking in summer heat and sun a few months ago.