IN WHICH A SMALL GAS MOLECULE HAS A BIG EFFECT

It’s a Gas

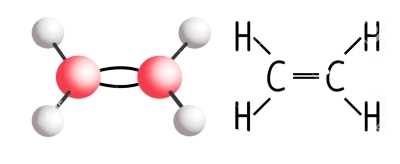

Ethylene is so simple. It’s a gas made up of merely two atoms of carbon and four atoms of hydrogen. Simple gases are generally not the kinds of molecules that make plant hormones which, like human hormones, are generally complex molecules with dramatic effects at extremely low concentrations. Nonetheless, ethylene is a plant hormone. I thought of ethylene as I sunk my teeth into the last garden-fresh peppers of the season a couple of weeks ago. Note that I wrote “fresh,” not “fresh-picked.”

Those peppers were picked week or two before being eaten. I picked any green peppers showing the slightest hints of red, then spread them out on a tray. Many gardeners do this with tomatoes. I like peppers a lot more than tomatoes so only occasionally try to prolonging the season of fresh tomatoes.

It’s ethylene that’s responsible for the transformations from unripe to ripe. Ethylene is produced naturally in ripening fruits, and its very presence — even at concentrations as low as 0.001 percent — stimulates, in turn, further ripening. The ethylene given off by ripe apples can be used to hurry along ripening of peppers or tomatoes, by placing an apple in a closed bag with them.

If the fruits are left too long in the bag, ethylene will stimulate ripening which will stimulate more ethylene which will stimulate even more ripening which will stimulate more ethylene which will stimulate still more ripening, ad infinitum, until what is left is a bag of mushy, rotten fruit. Apples can do this to each other, so one rotten apple really can spoil a whole barrel of them.

Banana, apple, pepper, tomato, and avocado are among so-called climacteric fruits, which undergo a burst of respiration and ethylene production — their “climacteric” — as ripening begins. These fruits, if picked sufficiently mature, can, like my peppers, ripen following harvest. Soon after their climacteric, these fruits start their decline. (I question whether the color and flavor changes associated with ripening of climacteric fruits after harvest match flavor development of these fruits when allowed to fully ripen on the plants. Ripening on the plant, of course, introduces other variables, such as sunlight, which also influence flavor.)

Citrus, fig, strawberry, and raspberry are examples of nonclimacteric fruits, whose ripening proceeds more calmly. Nonclimacteric fruits will not ripen at all after they’ve been harvested. They might soften and sweeten as complex carbohydrates break down into simple sugars, but such changes might be more indicative of incipient rot rather than ripening or flavor enhancement.

(This post is adapted from my book, The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden, at www.leereich.com/books)

Some History

Over the centuries, ethylene has sometimes unknowingly been applied to growing plants or stored fruits. The Chinese used burning incense to get pears to ripen (burning gives off a small amount of ethylene). A century ago, the skins of oranges shipped North from Florida morphed from green to orange in railroad cars heated with kerosene stoves.

It wasn’t until 1934 that a scientist discovered that ethylene is produced in plants and stimulates ripening. These days, ethylene is applied knowingly by farmers with a chemical commonly known as Ethrel. When plants are sprayed with Ethrel, it changes to ethylene. In an effort to thwart ethylene production—to put the brakes on fruit ripening, to keep harvested, ripe fruit in good condition longer, or to delay fruit drop from a plant — chemical inhibitors, such as 1-Methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) and aminooxyacetic acid (AOA) have also been developed. In my refrigerator hydrator drawers are some packets I bought to absorb ethylene and keep produce fresh longer.

All Sorts of Effects

Ethylene has effects other than hastening fruit ripening. It also can slow rampant shoot growth — sometimes, in so doing, diverting a plant’s energy into making flowers and fruits. Puerto Rican pineapple growers used to build bonfires near their fields to get the plants to start fruiting sooner. On a windowsill, a potted pineapple plant can be persuaded to flower by enclosing the whole plant in a bag with an apple for awhile. Commercial apple trees which are growing only stems sometimes are sprayed early in the season with Ethrel to get them to settle down and start fruiting. It can also hasten fruit coloring and/or ripening and loosen fruit for easier harvest. It’s all a matter of timing, concentration, and physiological state of the plant.

Fruit ripening and ethylene itself are not the only stimuli to ethylene production in plants. If a leaf is damaged, or even gently rubbed, its cells start emanating ethylene.

Blossom end rot of these tomatoes possibly coaxing ripening

The same is true with branches bent or whipped in the wind. There may be something to the folklore of beating an apple tree to induce it to fruit.

Just as ethylene hastens ripening, then senescence, of fruits, it also hastens senescence of leaves and flowers. A leaf might yellow, then drop, partly in response to ethylene production following insect or disease damage. Cut flowers fade depending on how much ethylene they are producing, both from aging and in response to being cut. Adding a floral preservative, such as silver thiosulfate, to the water in a vase works by putting the brakes on ethylene production.

Doe Hill pepper ripening

When I pick my end-of-season peppers, I’m especially careful to pick only undamaged fruit. Damaged portions of a fruit would produce more ethylene, then ripen and rot too quickly. Some gardeners wrap each harvested tomatoes in newspaper, which accelerates ripening by slowing ethylene diffusion from the fruits. Peppers should respond similarly.

I keep my end-of-season peppers and tomatoes unwrapped so I can keep an eye on them, moving any rotten ones to the compost pile and the ripe ones to the cutting board.

[Fresh peppers and tomatoes well into fall even here on the farmden. No problem, especially with a little know-how about a simple molecule made up of merely two atoms of carbon and four atoms of hydrogen, ethylene. Although simple, it has far-reaching effects and is found naturally in all plants and plant parts. Read about ethylene and working with it in my latest blog post.}

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!