The Season Begins

One More Thing? Ha!

I have one more important task to do before planting any vegetables this spring, and that is the annual mapping out of the garden, something I generally put off as long as possible.

In theory, mapping out my garden should be easy. I “rotate” what I plant in each bed so that no vegetable, or any of its relatives, grows in a given bed more frequently than every 3 years.  In practice, I mostly pay attention to rotation of plants most susceptible to diseases, which are cabbage and its kin (all in the Brassicaceae), cucumber and its kin (Cucurbitaceae), tomato and its kin (Solanaceae), beans and peas (Fabaceae), and corn (sweet or pop, in the Gramineae).

In practice, I mostly pay attention to rotation of plants most susceptible to diseases, which are cabbage and its kin (all in the Brassicaceae), cucumber and its kin (Cucurbitaceae), tomato and its kin (Solanaceae), beans and peas (Fabaceae), and corn (sweet or pop, in the Gramineae).

Crop rotation prevents buildup of disease pests that overwinter in the ground; removing host plants eventually starves them out. (Insect pest are more mobile, so crop rotation has less impact except in very large plantings.) So one year a bed might be home to cucumbers, melons or squashes. The next year that bed might host cabbage, broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, or cauliflower. Then tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, or eggplants. And finally, the fourth year, back to cucumbers. Simple enough.

It would also be nice to rotate carrots and other root vegetables with leafy vegetables, such as lettuce, and fruiting vegetables, such as tomatoes.  Root, leafy, and fruiting vegetables have somewhat different nutrient needs, so in the ideal garden these crops are rotated to make best use of soil nutrients.

Root, leafy, and fruiting vegetables have somewhat different nutrient needs, so in the ideal garden these crops are rotated to make best use of soil nutrients.

And I do like to get the most out of my garden and confuse potential insect pests by grouping different kinds of plants within a bed.

Are you beginning to understand why I put off committing my garden plan to paper each spring?

Pea Problem(s)

Peas present one more wrinkle in my vegetable garden planning. A few years ago they stopped bearing well, collapsing with yellowing foliage not long after they bore their first pods.

A few years ago they stopped bearing well, collapsing with yellowing foliage not long after they bore their first pods.

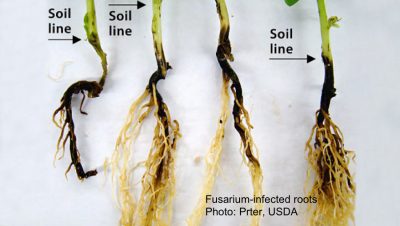

Further investigation has narrowed the problem to – probably – one of two diseases: fusarium or aphanomyces. Both, unfortunately, are long-lived in the soil so that a 3 year rotation does nothing to keep them in check.

Fortunately, I have two vegetable gardens. So, for the past few years I have banned peas from my north garden, planting them only in my south garden, in which they do get rotated. After a few more years, I’ll move the pea show to my north garden and leave my south garden pea-less. I’ve also been planting the varieties Green Arrow and Little Marvel, both of which are resistant to fusarium, at least.

Unfortunately, the problem is more likely aphanomyces, for which resistant varieties do not exist. Aphanomyces is a water mold, so thrives under wet conditions. So my tack will also be to keep any peas planted in my vegetable garden on the dry side, not even turning on the drip irrigation in those beds.

I’ll also be checking the plants more closely for symptoms. Plants infected by fusarium have a red discoloration to their roots.  Plants infected by aphanomyces have fewer branch roots and what roots there are lack the plump, white appearance of healthy roots.

Plants infected by aphanomyces have fewer branch roots and what roots there are lack the plump, white appearance of healthy roots.

Pea Solution?

I’m also testing out root drenches with compost tea for my peas.

Yes, yes, I know I have dissed compost tea in the past. Mostly, its benefits, if any, have been overstated. But compost microbes have more chance of surviving in the dark, moist, nutrient-rich environment of the soil than on a leaf, where the stuff is often sprayed. I’m drenching the soil with the tea, not just giving the surface a spray, as usually recommended, so a lot more bacteria, fungi and friends are finding their way down there.

I see no reason (and research does not support) of going to the trouble of making the usual compost tea, which is aerated and might be fortified with such things as molasses.  My tea is nothing more than the liquid strained from compost soaked in water, then applied with a watering can at the base of the pea plants.

My tea is nothing more than the liquid strained from compost soaked in water, then applied with a watering can at the base of the pea plants.

I’ve done this for a couple of seasons but have nothing definite to report yet. The hard part is sacrificing a bed as a control. Perhaps this year.

And what about winter? A greenhouse full of salad and cooking greens solved that problem, in addition to providing figs in summer and early and late season cucumbers.

And what about winter? A greenhouse full of salad and cooking greens solved that problem, in addition to providing figs in summer and early and late season cucumbers.

For the past few years, I’ve allowed celery in the greenhouse to go to seed each fall. The seeds drop and, within a few months, sprout to furnish plenty of seedlings for early summer celery in the greenhouse and later celery out in the garden. All of which is most welcome because celery seedlings are very slow to germinate and grow. Before celery volunteered around here, I had to sow seeds in early February in seed flats, keep the flats warm and moist until the seeds sprouted, transplant the sprouts into individual cells in another flat, and finally transplant the seedlings, after about 10 weeks of care, out into their permanent homes.

For the past few years, I’ve allowed celery in the greenhouse to go to seed each fall. The seeds drop and, within a few months, sprout to furnish plenty of seedlings for early summer celery in the greenhouse and later celery out in the garden. All of which is most welcome because celery seedlings are very slow to germinate and grow. Before celery volunteered around here, I had to sow seeds in early February in seed flats, keep the flats warm and moist until the seeds sprouted, transplant the sprouts into individual cells in another flat, and finally transplant the seedlings, after about 10 weeks of care, out into their permanent homes.

The flowers don’t exactly jump out at you so you have to get up pretty close to even notice them. Still, they are a sign of plant life in the depths of winter.

The flowers don’t exactly jump out at you so you have to get up pretty close to even notice them. Still, they are a sign of plant life in the depths of winter.

Usually the plant is pest-free but a few years ago something, perhaps a fungus, perhaps an insect, started attacking it, leaving the flesh dry and crumbly. I have yet to identify the culprit so that appropriate action can be taken.

Usually the plant is pest-free but a few years ago something, perhaps a fungus, perhaps an insect, started attacking it, leaving the flesh dry and crumbly. I have yet to identify the culprit so that appropriate action can be taken.

Roots of Rabbi Samuel fig, near the endwall, spread under the wall and outside the greenhouse, soaking up so much water that the figs split before ripening. Yet, a few fig fruits escape both afflictions and ripen to juicy sweetness.

Roots of Rabbi Samuel fig, near the endwall, spread under the wall and outside the greenhouse, soaking up so much water that the figs split before ripening. Yet, a few fig fruits escape both afflictions and ripen to juicy sweetness.

Also enjoying this awful weather are the oat cover crops that I’ve sown in some of my vegetable beds. The oats are especially lush and green, as is your and my lawn grass. The same goes for beds I recently planted with lettuce, radishes, arugula, turnips and other cool weather vegetables.

Also enjoying this awful weather are the oat cover crops that I’ve sown in some of my vegetable beds. The oats are especially lush and green, as is your and my lawn grass. The same goes for beds I recently planted with lettuce, radishes, arugula, turnips and other cool weather vegetables.

Buckwheat provides a quick and temporary cover of the bare ground. Sprinkling it with water assured its getting off to a quick start.

Buckwheat provides a quick and temporary cover of the bare ground. Sprinkling it with water assured its getting off to a quick start. Below ground, the roots were latching onto nutrients that might otherwise leach away, bringing them up into the roots, stems, and leaves.

Below ground, the roots were latching onto nutrients that might otherwise leach away, bringing them up into the roots, stems, and leaves. So any bed no longer needed for autumn vegetables and cleared before about the end of September gets oats (and compost). After the end of September, short days don’t provide enough light for the oats to grow enough to warrant planting.

So any bed no longer needed for autumn vegetables and cleared before about the end of September gets oats (and compost). After the end of September, short days don’t provide enough light for the oats to grow enough to warrant planting. While I have great respect for soil, it’s not pretty to look at — and being bared isn’t good for the soil or the plants growing in it. I’d much rather look at a uniform, green carpet than bare, brown soil.

While I have great respect for soil, it’s not pretty to look at — and being bared isn’t good for the soil or the plants growing in it. I’d much rather look at a uniform, green carpet than bare, brown soil. As it turns out, even taste is a matter of taste: To me, Garden Gem is not a great-tasting tomato; not even a good-tasting tomato. It lacked any sweetness or richness to smooth out the acidity, which is basically all I tasted.

As it turns out, even taste is a matter of taste: To me, Garden Gem is not a great-tasting tomato; not even a good-tasting tomato. It lacked any sweetness or richness to smooth out the acidity, which is basically all I tasted.