GUT PLANTING

Not My Usual Approach

I couldn’t help myself, so yesterday I broke protocol. After quite a few days of bright sunshine with daytime temperatures in the 70s, even the 80s a couple of days, I went ahead and planted all the tomato and pepper plants that I’ve been nurturing since their birth a few weeks ago — six weeks for the tomatoes, ten weeks for the peppers. Looking ahead, warm sunny days should follow, with night temperatures are predicted to dip down only into the 50s.

My usual protocol has been to plant not with my gut, but with the calendar date. Over the years I’m come up with a detailed chart of when to sow and transplant different kinds of vegetables based on the average dates of the last killing frost. Here, that date is around May 21st. Or, it used to be. (That chart — which I included in my book Weedless Gardening — allows anyone anywhere to determine sowing and planting dates merely by plugging in the average date for the last killing frost for their garden. Last frost dates for specific locations are available online.)

As with other global warming trends, the average date of the last killing frost right here — meaning specifically in my garden, which is in a frost pocket — has been pushed back a week or more. In the past, I would wait until a week, even two weeks, after that last frost date to set tomato and pepper plants in the garden. The average frost date is just an average; that week or two made sure my plants wouldn’t be caught off guard by a clear, cold night that didn’t hew to averages and charts.

When it comes right down to it, early planting is a gamble. The odds were good, so I took the gamble. My actions were also shaded by my not wanting to repot all the seedlings that were soon to outgrow their containers, and my hankering to see my garden with lots of plants in it.

Frost or Freeze

The word “frost” allows for some wiggle room. You’d think it meant any temperature below 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Not so. Temperatures between 29 and 32 degrees could be called a “light freeze.” Peppers and tomatoes sufficiently toughened up (“hardened off”) with some exposure to bright sunlight, cool temperatures, and wind can cruise right through a light freeze unscathed.

Moderate freezes, 25 to 28 degrees F., would cause some damage. A severe freeze, with temperatures below 24 degrees F. spells trouble for any tender vegetables plant. Sufficiently hardened off cool season plants, such as cabbage and its kin, lettuce, and chard, are usually fine even at those temperatures.

In all this, whether or not damage or death occur must factor in how fast cold descends on the garden, and how long it sits around.

At this point, I’m confident that my plants will be fine. If Ol’ Man Winter decides to peek in again, I can always throw a cover — flower pots, sheets, row cover — over the plants to protect them from cold.

Upright Pepper Plants

Let’s shift gears and take a look at growing peppers, specifically, keeping them upright. My pepper plants, and perhaps yours, become top heavy with their weight of maturing fruit. Mine especially so because I don’t pick any until they have fully matured, turning red or whatever other color they sport at full maturity. Especially prone to toppling is the variety Sweet Italia, which I grow because of its especially luscious fruits which also ripen early.

I’ve tried various methods of keeping Sweet Italia’s fruit laden stems up. In the past, I grew them in those cone shaped, wire cages often sold for tomatoes, for which they are useless. Those cages get tangled together in storage and make weeding very difficult. My bamboo provides an excess of stakes of various thickness; three stakes next to a plant does keep the plant upright, but not its fruit-laden arms.

Twine woven in among the plants and tied to metal stakes set a few feet apart along the row held plants and most arms up, but scrunched everything together too much, cutting down light penetration.

This year my plants are going to stand up with the help of livestock fencing panels, cattle panels with 6×8 inch openings, and goat and sheep panels with 4×4 inch openings. With a bolt cutter I clipped them into one-square-wide strips. Each bed is home to two rows, about 20 inches apart, of peppers, with plants set 16 inches apart in the row. Sixteen inch spacing allows me to set the panel strips centered over the plants. For now the strips are on the ground beneath the plants.

Once the plants grow large and start extending their arms, I’ll raise the strips with some bricks set every few feet as high as needed to do their job.

I hope this works, and welcome any comments on the prognosis. Do you have a method for successfully keeping your peppers from toppling or resting too many fruits on the ground? Perhaps your peppers grow unaided?

That inch depth of compost is the only thing my vegetable beds get each year, and it nourishes closely planted cabbages, tomatoes, lettuces, and other plants from the first breath of spring until cold weather barrels in to shut down production.

That inch depth of compost is the only thing my vegetable beds get each year, and it nourishes closely planted cabbages, tomatoes, lettuces, and other plants from the first breath of spring until cold weather barrels in to shut down production.

Then I pile up on the floor two gallons each of garden soil, peat moss, perlite, and compost. On top of the mound I sprinkle a cup of lime (except if I’ve sprinkled limestone on the compost piles as I build them), a half cup soybean, perhaps some kelp flakes.

Then I pile up on the floor two gallons each of garden soil, peat moss, perlite, and compost. On top of the mound I sprinkle a cup of lime (except if I’ve sprinkled limestone on the compost piles as I build them), a half cup soybean, perhaps some kelp flakes. I moisten it slightly if it seems dry. When all mixed, the potting soil gets rubbed through a 1/2″ sieve, 1/4” if it’s going to be home for seedlings.

I moisten it slightly if it seems dry. When all mixed, the potting soil gets rubbed through a 1/2″ sieve, 1/4” if it’s going to be home for seedlings.

To the south my meadow ends at a sweep of another neighbor’s field, the more frequently mown grass of which undulate like waves in summer sunshine in contrast to the more upright asters, fleabanes, goldenrods, and monardas that stand upright among the grasses in my meadow.

To the south my meadow ends at a sweep of another neighbor’s field, the more frequently mown grass of which undulate like waves in summer sunshine in contrast to the more upright asters, fleabanes, goldenrods, and monardas that stand upright among the grasses in my meadow.

Besides having its thirst quenched just enough to prevent wilting, it sits in front of a large, unobstructed window facing due south in a room whose temperatures range from the 50s and 60s. (That’s why I’m writing while sitting here in a down jacket!)

Besides having its thirst quenched just enough to prevent wilting, it sits in front of a large, unobstructed window facing due south in a room whose temperatures range from the 50s and 60s. (That’s why I’m writing while sitting here in a down jacket!) The larger the plant, the more roots can be removed. I go around the edge of the root ball with a kitchen knife slicing an inch or two off around the edge of the root ball. That should tell Ms. Fig to chillax!

The larger the plant, the more roots can be removed. I go around the edge of the root ball with a kitchen knife slicing an inch or two off around the edge of the root ball. That should tell Ms. Fig to chillax!

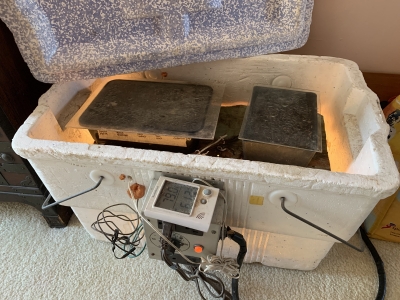

So I sowed them in a 4×6 inch seed flat filled with potting soil, then moved the flat in front of a sun-drenched, living room window. Once the lettuce seeds sprouted, which was in a few days, I moved them to the greenhouse. Warmer temperatures are needed to sprout a seed than to grow a plant.

So I sowed them in a 4×6 inch seed flat filled with potting soil, then moved the flat in front of a sun-drenched, living room window. Once the lettuce seeds sprouted, which was in a few days, I moved them to the greenhouse. Warmer temperatures are needed to sprout a seed than to grow a plant.

I use this same method to keep up a steady supply of lettuce and other seedlings all through summer, the plants typically needing about a month in the

I use this same method to keep up a steady supply of lettuce and other seedlings all through summer, the plants typically needing about a month in the

Shellbark hickory’s native range doesn’t extend as far east and south as shagbark’s. It’s found mostly along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, and bordering regions; nowhere, though, is it common. Also, the bark is less shaggy. The clincher is that shellbark nuts are much larger, around two inches long, and with thinner shells, so you get more bang for your buck with each nut you crack.

Shellbark hickory’s native range doesn’t extend as far east and south as shagbark’s. It’s found mostly along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, and bordering regions; nowhere, though, is it common. Also, the bark is less shaggy. The clincher is that shellbark nuts are much larger, around two inches long, and with thinner shells, so you get more bang for your buck with each nut you crack.