SWEET POSSIBILITIES

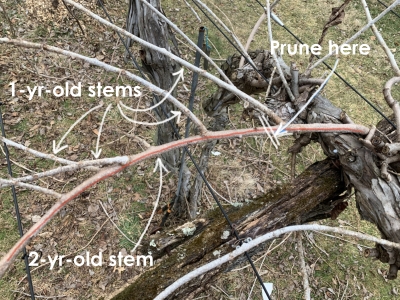

It’s time to prune, and to help you, I’ll be holding a PRUNING WEBINAR on March 29, 7-8:30 EST. Learn the tools of the trade, how plants respond to pruning, details for pruning various plants, and enjoy a fun finale on an easy espalier. There’ll be time for questions also. Cost is $35 and you can register with Paypal or credit card here.

Choice Syrups

I’ve given up on maple syrup this year. The tree I tapped was too small to yield anything significant.

I’d almost given up on river birch syrup. I thought perhaps it was the timing — and, have since learned, that it is! Sap from any one of a number of birch species doesn’t begin to flow until temperatures are consistently 50°F or higher, which arrives near the end of the maple tapping season and continues until about the time the trees leaf out.

River birch, tapped

Black walnut was another possibility for tapping. I previously had pooh-poohed it because, much as I love this tree’s nuts, I imagined the aroma of the leaves or the hulls oozing its way into the sap. Ugh!

Another reader reported that walnut syrup is delicious and I should try it, so I did. Sap started dripping as soon as I drilled the holes. The first batch is boiled down, and it is delicious. Not that different from maple syrup, with just a slightly different, smoother flavor. Nothing reminiscent of the nuts, leaves, or husks, though.

Black walnut tree, tapped

Processing was via the same low-tech approach I’ve used for maple syrup, merely adding each day’s “catch” to a big stock pot sitting on the wood stove. The woodstove is stoked pretty much continuously this time of year, so the sap is always evaporating, with the added bonus of humidifying the house.

I see a few eyebrows going up. Sticky walls and ceiling are what comes to some minds upon the mention of cooking down maple sap indoors. Well, that’s usually myth. Sticky walls and ceiling only result when the sap is in an active boil and bubbles bursting on the surface of the liquid send little droplets of sugar water into the air and onto walls and ceilings.

Until the final stage of my sap-making, the sap is just slowly evaporating. The vapor given off by slowly evaporating, simmering, or boiling a solution of any sugar and water is nothing more than water vapor. That’s why the maple (or black walnut) sugars become concentrated in the remaining liquid. They stay in the pot.

In those final stages of concentration, with much reduced liquid volume, the liquid can indeed reach an active boil. The pot of liquid announces that it’s nearing that stage by starting to gurgle like a baby, at which point it needs to be watched closely, mostly so that the syrup doesn’t get too concentrated or burn. The finish point is when the temperature of the liquid reaches about 219 degrees F.

I discovered a big difference from maple syruping when I attempted to strain off schmutz in the boiled down black walnut sap. The schmutz was a jelly that quickly clogged up the strainer. The amount of schmutz can vary from tree to tree, with time of year, and who knows what else. Turns out that black walnut sap is high in pectin, aka schmutz. Perhaps calling it “black walnut jelly” would make it more appetizing.

Too Late to Prune, Say the Squirrels?

Someone wrote me that squirrels were chewing on a Norway maple last week and the sap was seen dripping down, then went on to ask if that meant it was too late to prune. Perhaps the squirrels were enjoying some of the sweet sap.

Yes, you can tap and boil into syrup the sap of all kinds of maples; I’ve tapped and made syrup from silver maple, red maple, boxelder, and, of course, sugar maple. And each tastes slightly different from the other.

Getting back the pruning… It’s not at all too late. It’s fine to “dormant” prune any plants up until the time when they unfurl their leaves in spring. Actually, peach trees are best pruned when they are blooming.

Another good question might be: Why not just cut the Norway maple down to the ground? The trees are invasive and displacing our sugar maples, they have poor fall color, and they create lugubrious shade beneath which grass and much else can’t grow. Mostly, people keep these trees because they are already in place and full grown.

Topics will include:

Topics will include:

This allowed me to draw some of the air out of the jars with a tube connecting the pump to a ‘FoodSaver Wide-Mouth Jar Sealer.’ It did (usually) create somewhat of a vacuum but it was too much trouble to get at the seeds and re-seal a jar each time. And, again, seed packets don’t pack well into canning jars.

This allowed me to draw some of the air out of the jars with a tube connecting the pump to a ‘FoodSaver Wide-Mouth Jar Sealer.’ It did (usually) create somewhat of a vacuum but it was too much trouble to get at the seeds and re-seal a jar each time. And, again, seed packets don’t pack well into canning jars.

The one on my garden gate is especially useful in spring and fall, when frosts threaten. As soon as the snow melts, my third

The one on my garden gate is especially useful in spring and fall, when frosts threaten. As soon as the snow melts, my third

I figured I could spread it on the ground beneath some of my trees and shrubs, especially the youngest ones. There, next summer, the mulch would keep weeds at bay, slow evaporation of water from the ground, and feed soil life, in so doing enriching the soil with nutrients and organic matter.

I figured I could spread it on the ground beneath some of my trees and shrubs, especially the youngest ones. There, next summer, the mulch would keep weeds at bay, slow evaporation of water from the ground, and feed soil life, in so doing enriching the soil with nutrients and organic matter. Chips there are mostly to suppress weeds which thrived with last season’s unusually abundant rainfall and to soften, by spreading out, the impact of footfall on the paths. I generally “chip the paths” every couple of years at a minimum if for nothing more so that the height of the paths keeps up with the rising height of the vegetable beds which get — and already got, at the end of this season — a one-inch deep blanket of compost annually. (Besides the usual benefits of mulches, the compost provides enough nutrients for the intensively planted vegetables for the whole season. No fertilizer per se is needed.)

Chips there are mostly to suppress weeds which thrived with last season’s unusually abundant rainfall and to soften, by spreading out, the impact of footfall on the paths. I generally “chip the paths” every couple of years at a minimum if for nothing more so that the height of the paths keeps up with the rising height of the vegetable beds which get — and already got, at the end of this season — a one-inch deep blanket of compost annually. (Besides the usual benefits of mulches, the compost provides enough nutrients for the intensively planted vegetables for the whole season. No fertilizer per se is needed.) Like the stems of any other plant, a strawberry stem each year grows longer from its tip and also grows side shoots. So a strawberry stem rises ever so slowly higher up out of the soil each year.

Like the stems of any other plant, a strawberry stem each year grows longer from its tip and also grows side shoots. So a strawberry stem rises ever so slowly higher up out of the soil each year. Mulching too early might cause the stems to rot. I typically wait until the ground has frozen about an inch deep which usually occurs towards the end of December here, and then cover the plants with about an inch depth of wood shavings.

Mulching too early might cause the stems to rot. I typically wait until the ground has frozen about an inch deep which usually occurs towards the end of December here, and then cover the plants with about an inch depth of wood shavings.