UNPERMACULTURE

Accusations, (Mostly) not True

I’ve understandably been accused of being a “permie,” that is, of practicing permaculture.

(In the words of permaculture founder, Bill Mollison, “Permaculture is about designing sustainable human settlements. It is a philosophy and an approach to land use which weaves together microclimate, annual and perennial plants, animals, soils, water management, and human needs into intricately connected, productive communities.” In the words of www.dictionary.com, permaculture is “a system of cultivation intended to maintain permanent agriculture or horticulture by relying on renewable resources and a self-sustaining ecosystem.”)

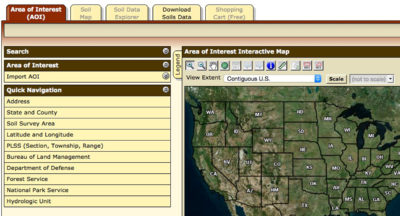

Walk around my farmden and, yes, you’ll come upon Nanking cherry bushes where forsythia bushes once lined the driveway, an American persimmon tree where a lilac bush once stood, and other edible plants used also for landscaping. In the vegetable garden, I preserve soil integrity by never tilling it, and, in the south field, blackcurrant bushes make use of the space beneath pawpaw trees. There’s the requisite mushroom yard of shiitake-inoculated logs, free-range poultry, solar panels, a rain barrel . . .

Pawpaws interplanted with blackcurrants, and a row of hardy kiwis

But no! I am not a permie. My vegetables grow in beds in parallel, straight rows (rather than keyhole plantings) and, despite that commingling of blackcurrants and pawpaws, most trees, shrubs, and vines here keep to themselves. Permaculture plantings of, say, hazelnuts in tall grass and rubbing elbows with elderberries, seaberries, apples, pears, and other edibles become, over time, an unproductive management nightmare with some plants drowning out others, productivity declining due to shade, and diseases increasing from tangled stems creating dank conditions. The paltry output of such planting are best left for wildlife, who can afford to spend all day foraging for a few tidbits of food.

My hazelnuts are grown in a mown strip that, for easy gathering, is sheared low as nuts ripen.

Low maintenance is a goal touted by permaculturalists; understandably so. But taken to the extreme, low maintenance means not giving the grape vine the pruning it needs to be a healthy vine yielding the most flavorful berries that are easy to harvest. (One book suggests, rather than troubling with a trellis, growing grape vines up trees; the vines do so in the wild, but such fruit, in partial shade and not easily accessible, can never be high quality.)

Much of permaculture seems to me to be not only unrealistic, but also no fun. I enjoy caring for my plants, reaping the gustatory and other rewards for a job well done. I like the challenge of researching some pest or nutritional problem and finding a solution. I like watching how plants respond to my ministrations, whether I’m wielding pruning shears, a pitchfork piled high with compost, or my winged weeder hoe.

Agriculture is about balancing Nature’s designs and human will. Too much of the latter is a losing battle. Too much of the former leaves nothing worth harvesting.

Big Bantam, an Oymoron

My planting of sweet corn is very un-permaculture. It’s high-culture: 6 seeds per hill dropped into compost-enriched ground maintained weed-free, timely watering with drip irrigation, hills thinned to 3 stalks per hill, even stakes to keep the stalks standing soldier straight. I mentioned, last week, how my Golden Bantam variety of sweet corn isn’t bantam at all. The stalks soar over 10 feet high.

Was it because of my green thumb? No. I now know that it is genetics.

This year I made four plantings of Golden Bantam. The two later plantings are, in fact, bantam-size. Looking over my seed orders, I see that I had planted Golden Bantam Corn, Original 8-row Golden Bantam Corn, and Improved Golden Bantam Corn.

Golden Bantam is an open-pollinated variety. As with any open-pollinated variety, various strains might arise, strains which might differ in some ways from the original. With any good variety, the hope is that progeny are monitored to eliminate any off-type varieties — or to look for something that might be better than the original.

Golden Bantams compared

So the name Golden Bantam could be attached to the original Golden Bantam, from 1902, or any strain, which could also have “Improved,” “Original,” etc. attached its name. (Golden Bantam was also developed into a hybrid, Golden Cross Bantam, which, like other hybrids, would be genetically more consistent and ripen in a shorter window of time.)

On the theory that bigger is better, “Improved” was tacked onto name of the strain of my early plantings. The original Golden Bantam was 8-row; Improved Golden Bantam is 10 to 14 row. I should have read the catalog more closely because Improved Golden Bantam casts too much shade, ripens too late for my intensively planted vegetables, and yields less, with but a single ear per stalk. The original also has better flavor, to me.

Permaculture, but not by Me

Walking down the main path of my vegetable garden yesterday, you’d come upon a very permaculturalesque planting — in the path. The path was overrun with purslane, which I didn’t even have to plant. Purslane is a tasty, very nutritious vegetable enjoyed raw or cooked. But not by me.

I grabbed my winged weeder and hoed the purslane loose from the soil. As a succulent, purslane can continue to grow — and seed! — even with its roots flailing in the air. So after hoeing, I scooped the plants up to feed to the compost file.