CLOSING “SHOP”

Chips, Not Hay, In This Case

“Make hay while the sun shines.” Good advice, literally in agriculture and figuratively in life. And I’m following it these days, in agriculture. Not making hay of course, because that sunshine is only effective in summer and fall, partnered with heat.

The “hay that I’m making” is actually mulch that I’m spreading. A few weeks ago I put my “WOOD CHIPS WANTED” sign out along the road in front of my house. In a short time, an arborist was kind enough deposit a truckload of chips.  I figured I could spread it on the ground beneath some of my trees and shrubs, especially the youngest ones. There, next summer, the mulch would keep weeds at bay, slow evaporation of water from the ground, and feed soil life, in so doing enriching the soil with nutrients and organic matter.

I figured I could spread it on the ground beneath some of my trees and shrubs, especially the youngest ones. There, next summer, the mulch would keep weeds at bay, slow evaporation of water from the ground, and feed soil life, in so doing enriching the soil with nutrients and organic matter.

Usually, by this time of year, my piles of wood chips have frozen solid or are white mounds beneath snowy blankets. Not so this year.

So I’ve been loading up garden cart after garden cart with chips to haul over to the garden. (Once the ground disappears beneath a heavy, white layer of snow, moving heavy cartloads becomes nearly impossible.)

Since the most important trees and shrubs had already been mulched earlier in autumn, I decided it was a good time to add a layer of chips to the paths in the vegetable garden. Chips there are mostly to suppress weeds which thrived with last season’s unusually abundant rainfall and to soften, by spreading out, the impact of footfall on the paths. I generally “chip the paths” every couple of years at a minimum if for nothing more so that the height of the paths keeps up with the rising height of the vegetable beds which get — and already got, at the end of this season — a one-inch deep blanket of compost annually. (Besides the usual benefits of mulches, the compost provides enough nutrients for the intensively planted vegetables for the whole season. No fertilizer per se is needed.)

Chips there are mostly to suppress weeds which thrived with last season’s unusually abundant rainfall and to soften, by spreading out, the impact of footfall on the paths. I generally “chip the paths” every couple of years at a minimum if for nothing more so that the height of the paths keeps up with the rising height of the vegetable beds which get — and already got, at the end of this season — a one-inch deep blanket of compost annually. (Besides the usual benefits of mulches, the compost provides enough nutrients for the intensively planted vegetables for the whole season. No fertilizer per se is needed.)

After decades of my adding an inch or more of wood chips to the paths and compost to the beds, you might suppose that the whole vegetable garden has risen a few feet above the surrounding area like a giant stage. Nope. The goodness of organic materials, such as the compost and wood chips, comes from soil organisms chewing them up and breaking them down. As decomposition takes place, the bulk of these materials, which are mostly carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, is released into the air as carbon dioxide and water. The minerals that remain feed the plants.

Pine Berries?

One bed in the vegetable garden is home to strawberries. That bed also needs mulching, for different reasons and with different materials than the other beds, and needs it every year about now.

A strawberry plant is mostly nothing more than a stem, a stem whose distance from leaf to leaf has been telescoped down to create a stubby plant.  Like the stems of any other plant, a strawberry stem each year grows longer from its tip and also grows side shoots. So a strawberry stem rises ever so slowly higher up out of the soil each year.

Like the stems of any other plant, a strawberry stem each year grows longer from its tip and also grows side shoots. So a strawberry stem rises ever so slowly higher up out of the soil each year.

Strawberry stems are not super cold-hardy. As a stem slowly rises higher in the ground, it’s exposed to more and more cold, and more apt to dry out.

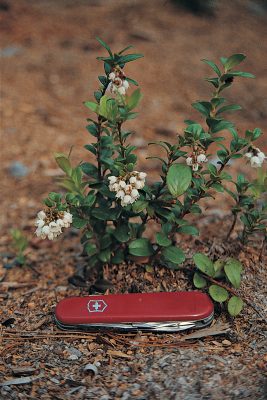

What’s needed is to protect the stems with an insulating blanket of some loose organic material. Straw is traditional — and one possible root of the name “strawberry” — but good straw reliably free of weed seeds is hard to find. Instead of straw, I often use wood shavings, conveniently available in bagged bales. This year I decided that the giant pine tree here could spare a few pine needles, raked up to share with the strawberries.

The goal of mulching strawberries isn’t to keep cold out, just to moderate the bitterest cold.  Mulching too early might cause the stems to rot. I typically wait until the ground has frozen about an inch deep which usually occurs towards the end of December here, and then cover the plants with about an inch depth of wood shavings.

Mulching too early might cause the stems to rot. I typically wait until the ground has frozen about an inch deep which usually occurs towards the end of December here, and then cover the plants with about an inch depth of wood shavings.

Come spring, the mulch needs to be pulled back before the plants start growing. Tucking the mulch in among the plants provides the usual benefits of mulch, especially important for strawberries because of their shallow roots, and provides a nice, clean bed on which the ripening berries can lie.

(More about growing strawberries can be found in my book GROW FRUIT NATURALLY.)

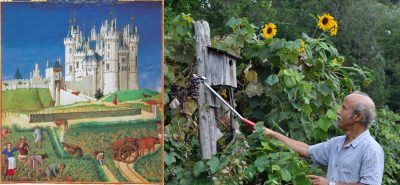

Hey, Good Looking

I admire the look of my vegetable gardens this time of year. With the chipped paths and compost lathered beds, some also with a tan cover of winter-killed oat plants, they look very tidy and ready to welcome new seeds and transplants in the months ahead. The look doesn’t compare with the lush greenery and colorful fruits of the summer garden, all of which is nothing more than a memory.

Only the slightest hint of bitterness remains, enough to make the taste more lively — delicious in salads, soups, and sandwiches.

Only the slightest hint of bitterness remains, enough to make the taste more lively — delicious in salads, soups, and sandwiches.

the pulp without seeds. No sweetener needed. Just jar it up and refrigerate (keeps about 2 weeks) or freeze. Delicious.

the pulp without seeds. No sweetener needed. Just jar it up and refrigerate (keeps about 2 weeks) or freeze. Delicious.

If any of this worked out, the plan was to use either the old-fashioned or modern method with a whole bunch of bunches in my walk-in, insulated and with some cooling or heating, as needed, fruit and vegetable storage room.

If any of this worked out, the plan was to use either the old-fashioned or modern method with a whole bunch of bunches in my walk-in, insulated and with some cooling or heating, as needed, fruit and vegetable storage room.

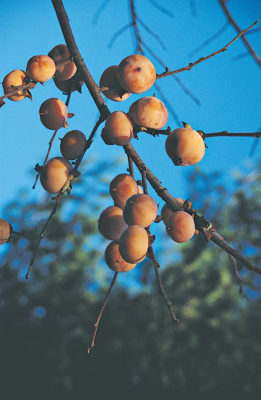

out Scandinavia, destined for sauce, juice, jam, wine, and baked goods. A fair number of these berries are, of course, just popped into appreciative mouths. Most everyone else only knows this fruit as a jam sold by Ikea.

out Scandinavia, destined for sauce, juice, jam, wine, and baked goods. A fair number of these berries are, of course, just popped into appreciative mouths. Most everyone else only knows this fruit as a jam sold by Ikea.

The first grapes of the season, Somerset Seedless and Glenora, started ripening towards the end of August. The first of these varieties is one of many bred by the late Wisconsin dairy farmer cum grape breeder Elmer Swenson. The fruits of his labors literally run the gamut from varieties, such as Edelweiss, having strong, foxy flavor (the characteristic flavor component of Concord grapes and many American-type grapes) to those with mild, fruity flavor reminiscent of European-type grapes. Somerset Seedless is more toward the latter end of the spectrum and, of course, it’s seedless. Swenson red and Briana, which are ripe as you read this, are more in the middle of the spectrum.

The first grapes of the season, Somerset Seedless and Glenora, started ripening towards the end of August. The first of these varieties is one of many bred by the late Wisconsin dairy farmer cum grape breeder Elmer Swenson. The fruits of his labors literally run the gamut from varieties, such as Edelweiss, having strong, foxy flavor (the characteristic flavor component of Concord grapes and many American-type grapes) to those with mild, fruity flavor reminiscent of European-type grapes. Somerset Seedless is more toward the latter end of the spectrum and, of course, it’s seedless. Swenson red and Briana, which are ripe as you read this, are more in the middle of the spectrum.

Perhaps the label made the bags even less attractive to grape-hungry birds and insects; at any rate, they worked very well, usually yielding almost 100 late harvest, delectably sweet and flavorful, perfect bunches of bagged grapes each year.

Perhaps the label made the bags even less attractive to grape-hungry birds and insects; at any rate, they worked very well, usually yielding almost 100 late harvest, delectably sweet and flavorful, perfect bunches of bagged grapes each year. Organza is an open weave fabric often made from synthetic fiber. Small organza bags typically enclose wedding favors; the bags come in many sizes. Organza bags have the advantage over paper bags of letting in more light. A mere pull of the two drawstrings makes bagging the fruit very easy; paper bags involve cutting, folding, and stapling. Organza bags also re-usable. (The bags also work well with apples which, in contrast to grapes, require sunlight to color up.)

Organza is an open weave fabric often made from synthetic fiber. Small organza bags typically enclose wedding favors; the bags come in many sizes. Organza bags have the advantage over paper bags of letting in more light. A mere pull of the two drawstrings makes bagging the fruit very easy; paper bags involve cutting, folding, and stapling. Organza bags also re-usable. (The bags also work well with apples which, in contrast to grapes, require sunlight to color up.)

This species is also relatively sedate in growth, so is easier to manage. One problem with this fruit, which my ducks and dogs consider a plus, is that it drops when it is ripe, perhaps because it’s ripening so quickly during hot days of summer.

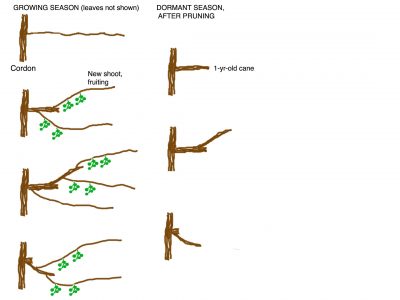

This species is also relatively sedate in growth, so is easier to manage. One problem with this fruit, which my ducks and dogs consider a plus, is that it drops when it is ripe, perhaps because it’s ripening so quickly during hot days of summer. Each plant’s strongest shoot has been trained to become a trunk that reaches the center wire, then bifurcates into two permanent arms, called cordons, running in opposite directions along the center wire.

Each plant’s strongest shoot has been trained to become a trunk that reaches the center wire, then bifurcates into two permanent arms, called cordons, running in opposite directions along the center wire.