NO SIGN OF SPRING HERE YET, BUT . . .

The Onion Cycle Begins Again

Early February, February 6th to be exact, was the official opening of my 2017 gardening season. No fireworks, waving flags, or other fanfare marked this opening. Just the whoosh of my trowel scooping potting soil into a seed flat, and then the hushed rattle of seeds in their paper packets. And the grand opening was not for a flamboyant, who-can-reap-the-earliest-meal of a vegetable like peas or tomatoes.

No, the grand opening for the season is rather sedate: I sowed onion seeds in mini-furrows in a seed flat. Why onions? In addition to the fact that I love the flavor of onions raw and cooked, onions need a long growing season. The summer growing season is cut short because the plants stop growing new leaves to put their energy into swelling up their bulbs when daylengths grow sufficiently long, 14 hours long, to be exact. Around here, that happens sometime in May. The more leaves the plants make before then, the bigger the bulbs. Hence my early planting.

So I poured about a 3-inch depth of potting soil into an 18 by 24 inch plastic tub in which I had drilled drainage holes, and then made seven parallel furrows in the soil into which I dropped onion seeds. This year I’m growing New York Early, Patterson, and Ailsa Craig. (I also sowed leeks in one of the furrows.) After closing up the furrows, I watered, covered the tub with a pane of glass, and put the tub on a heating mat set at 75 to 80° F.

Done. The season has begun.

Other Beginnings

There are so many ways to grow onions. Let me count the ways, some other ways.

1, and easiest, is to just plant onion sets, those mini-onions you can buy to plant as soon as the ground outside warms and dries up a bit. One downside to sets is that the variety selection is very limited. Not only limited, but also restricted to so-called “American-type” varieties, which keep very well but are very pungent and not very sweet. Onion sets that are too large — larger than a dime — tend to go to seed. Plants going to seed look very pretty but don’t make bulbs for eating.

Number 2 method overcomes one of the limitations of method number 1: Purchase onion plants, which are growing plants, with leaves. The sweet “European-types” — Ailsa Craig, Sweet Spanish, and Granex, for example — are available in this form. The plants are grown in fields in the South, and there’s the potential to bring a disease into the garden on these plants. Also, “organic” onion plants might be hard to find.

Setting out onion transplants

Method number 3 is the most involved. (I’ve never tried it.) Grow your own onion sets. The trick is to sow the seeds outdoors densely enough so that they bulb up while still small — dime size. Once bulbs mature, their harvested to store for winter, and then planted in spring just like the sets in Method 1.

Method number 4 is fairly easy, and that is to sow seeds of the Evergreen variety onions right in the ground in spring. This variety never forms bulbs but makes tasty green onions, or scallions. It’s also perennial, so any scallions left in the ground will multiply year after year. The downside here is that you don’t get onions for winter. I grow these every year and do get them for winter use also, in my greenhouse.

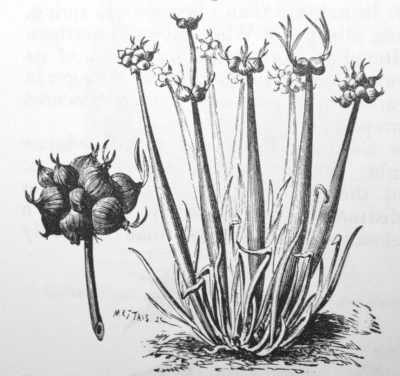

Method number 5 is easiest of all. Grow Egyptian, or Walking, onions. This is another perennial onion. It “walks” by forming bulblets on top of some stalks. The weight of the bulblets pulls down the stalk, and when the bulblets touch ground, they root to make new plants. The new plants eventually send up bulblet-topped stalks which likewise bend to the ground, etc., etc., walking the plants around. To me, Egyptian onions are all hotness with little other flavor. I no longer grow them.

Walking onions

I learned of method number 5 from Jay at Four Winds Farm. Simple enough. Just sow the seeds outdoors as soon as the ground is warm enough and dry enough for a nice seedbed. A nice seedbed is key here, because onions compete very poorly with weeds and the goal is to get the seeds to germinate as fast as possible. I tried this last year and the bulbs ended up pretty much the same size as those from the plants I sowed last February and then transplanted into the garden in April. So I get a wide choice of varieties without having to start the seeds in February. Thanks Jay. (I’m growing transplants and direct seeding this year, just to make sure.)

My Pea Planting Will Not Be On St. Pat’s Day!

My early February onion-sowing date isn’t some magical date. My greenhouse is only minimally heated, making for very slow growth early in the season. Growth picks up as sunlight grows more intense and further warms the greenhouse. A week or more difference in sowing date early in the season doesn’t translate into that much difference in growth near harvest time.

The same goes for pea-planting, which is attended by more fanfare than onion planting. Many gardeners rush to get their pea seeds planted by St. Patrick’s day, but planting a week later doesn’t delay that harvest by a week. Perhaps by a couple of days or by a few hours, depending on the season. And anyway, St. Patrick’s day might be the traditional date for planting peas in Ireland, but it would be way too early in Maine and way too late in Georgia. I plant peas here in Zone 5 on April 1st, give or take a few days.

In my book Weedless Gardening, I have a chart that shows what and when to plant, whether as seeds, indoors or out, or as transplants, for all regions. All you have to do is plug in your average date for the last killing frost of spring and the first killing frost of autumn. This date is available from your local Cooperative Extension Office.

(Autumn olive is often confused with Russian olive, E. angustifolium, a close relative that is more tree-like, less invasive, and with sweet, olive-green fruits. Another equally attractive, fragrant, tasty, and soil-building plant is gumi, E. multiflora, not well known but closely related to the other “olives.”)

(Autumn olive is often confused with Russian olive, E. angustifolium, a close relative that is more tree-like, less invasive, and with sweet, olive-green fruits. Another equally attractive, fragrant, tasty, and soil-building plant is gumi, E. multiflora, not well known but closely related to the other “olives.”)

Offer an explanation and, if correct, you’ll be in the pool of readers, one of whom, randomly selected, gets sent a free copy of my book

Offer an explanation and, if correct, you’ll be in the pool of readers, one of whom, randomly selected, gets sent a free copy of my book