LIBERATED, AT LAST

/25 Comments/in Gardening, Pests, Soil/by Lee ReichExposée

My garden was liberated yesterday, the soil freed at last. That’s when I peeled back and folded up the black tarps that had been covering some of the vegetable beds since early April. My beautiful soil finally popped into view.

Covering the ground was for the garden’s own good. “Tarping,” as this technique is called, gets the growing season off to a weed-less start. The black cover warms the ground to awaken weed seeds. They sprout, then die as they use up their energy reserves which, without light, can’t be replenished and built up. (I first learned of this technique in J. M. Fortier’s book The Market Gardener.)

Tarping is very different from the much more common way of growing plants in holes in black plastic film, even if one purpose of the soil covering, in both cases, is to snuff out weeds. Black plastic film is left in place all season long, and then disposed of, usually in a landfill, at season’s end.

Tarping tarps might be silage cover material or — as in my case — recycled, vinyl billboard signs (black on one side). They are left in place for relatively short duration, after which time the ground can be exposed to natural rainfall and air, and is open for blanketing with compost and cover crops. After each use, tarps can be folded up and stored for re-use for many seasons more.

Prescription for Weed-lessness

Tarping is but one part of my multi-pronged approach to weed control, the others of which I detail in my book Weedless Gardening.

My garden is also weed-less because I never, and I do mean never, till the soil, whether with a rototiller, garden fork, or shovel. Preserving the natural horizonation of the soil keeps weed seeds, which are coaxed awake by exposure to light, buried within the ground and dormant. No-till also has side benefits: preserving soil organic matter, maintaining soil capillarity for more efficient water use, and not disrupting soil fungi and other creatures.

Tilling does loosen the soil structure, but I avoid soil compaction by planting everything in 3-foot-wide beds, saving the paths between the beds for foot traffic.

Weed-lessness is also the result of each year covering the ground with a thin layer of a more or less weed-free mulch, just half inch to an inch thick depth. This covering snuffs out small weed seeds that might be present. Other benefits are insulating to modulate wide swings in soil temperature and softening the impact of raindrops so that water percolates into the ground rather than running off.

What I use for this thin layer of mulch depends on what’s available, what I’m mulching, and, sometimes, appearance. Vegetables are hungry plants so their beds get an inch depth of ripe compost, which, besides the other benefits of mulches, also provides all the nutrition the vegetable plants need for a whole season. Paths get wood chips; it’s free, it’s pretty, and it visually sets off paths from beds. Straw, autumn leaves, sawdust, and wood shavings are some other materials that would work as well.

At the end of the season, beds that have been harvested but aren’t needed for autumn cropping, get a cover crop, which is a plant grown specifically for soil improvement.

Cover crops provide all the benefits of mulches, plus looking pretty, sucking up nutrients that might otherwise wash through the soil in winter, and growing miles and miles of roots to give the soil a nice, crumbly structure. I plant oats or barley, because the plants thrive in cool autumn weather and then, here in Zone 5, are killed by winter cold sometime in January. The leaves flop down, dead, to become mulch, which I rake or roll up easily before it’s time for spring planting.

Another ploy for weed-lessness is using drip irrigation. Sure, I could get by without any watering here in the “humid Northeast,” but timely watering gets the most out of the garden. Drip irrigation pinpoints watering to garden plants rather weeds, which would, with a sprinkler, be coaxed to grow, for instance, in paths.

Weed-less but Not Weed-free

With this multi-pronged approach to weed-lessness, isn’t tarping like “taking coals to Newcastle?” No. I found that even after not tilling, mulching, using drip irrigation, and, especially, cover cropping, some weeds do a figurative “end run”and find their way into some beds. Especially, the last few years, red dead-nettle (Lamium purpureum).  Yes, I know the plant is pretty, provides early nectar for pollinators, and is edible. But its out of place in my vegetable beds. The tarp does it in.

Yes, I know the plant is pretty, provides early nectar for pollinators, and is edible. But its out of place in my vegetable beds. The tarp does it in.

No garden can be weedless. But mine has been weed-less for many, many years.

PERENNIAL VEGETABLES

/26 Comments/in Vegetables/by Lee ReichHablitzia: What a Name!

At last night’s appropriately social distanced “zoom” dinner with my daughter, she commented on how tasty my salad looked. “All home grown,” I replied, and held up to the computer screen a leaf of one of the major contributors to my bowl of greenery, Caucasian mountain spinach (Hablitzia tamnoides). “Looks like some leaf you just plucked off a tree,” says she. Yes, it did, but it was as tasty and as tender as any leaf of regular garden spinach.

It’s with good reason that the two “spinaches” are so similar: They’re both in the same family, Amaranthacea, also kin to beets, chard, quinoa, lamb’s quarters, and pigweed.

Caucasian mountain spinach has it over conventional garden spinach in a number of ways, most significantly its being a perennial. I planted it last spring and don’t plan on doing so ever again. Not that making new plants would be difficult. They were easy from seed, and cuttings are also said to root easily. The quickest way to have larger new plants would be to divide the clump sometime after the tops have died back for winter or before new sprouts appear.

Being a perennial, Caucasian mountain spinach won’t lose quality as it goes to seed during the warmer, longer days of late spring and summer. White flowers, with a faint aroma of cilantro, appear in June and July, but the leaves still make tasty additions to salads or cooked dishes.

Right now, plants are starting to stretch their leafy stems skyward. Making use of the third dimension in gardening — up — makes for efficient use of garden space, a plus for any plant in an intensive garden. They’d like something on which to climb, which they do by pulling themselves upward in the same way as do clematis vines, twisting their leaf stalks around whatever they can. I’ll be providing a ladder for them made from posts and chicken wire.

Now that I think of it, Caucasian mountain spinach also makes use of the fourth dimension in gardening — time — since it can make its way into the kitchen from when my plum trees bloom until I harvest the last of my apples.

The Good King, and Others

The bed that’s home to Caucasian mountain spinach is also home to another perennial bit of edible greenery, Good King Henry (Blitum bonus-henricus), also sharing the Amaranthacea family. That bed gets some shade in the afternoon, which is all to the liking of Caucasian mountain spinach, not so much to Good King Henry.

No matter, because Good King Henry is not, in my opinion, nearly as tasty as its Caucasian cousin. The King’s leaves are good cooked, but not great, and not very good raw in salads. One reason I like it so much is for its name, both the common name and the botanical name.

I had hoped the bed would also be home to the perennial leek and perennial onion (Welsh onion) that I sowed and grew last season. But there’s not a sign of either plant this season. I guess they’re not all that perennial, odd since last winter was downright tropical (for here), the thermometer hardly dipping below zero degrees Fahrenheit.

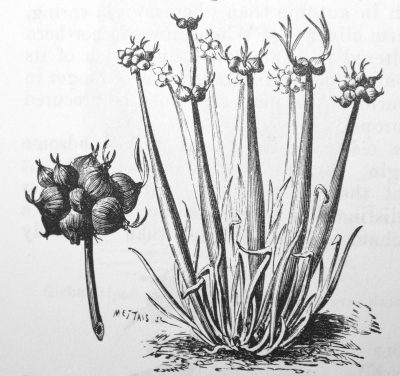

If I wanted early onions, as greens, some kinds are reliably hardy. An interesting one that I grew decades ago is Egyptian Onion, also known as Walking Onion. They “walk” because the cluster of small bulbs atop the green stalks weight the stalks down till they eventually bow to the ground, depositing the cluster a few inches from the plant.  The bulbs take root, grow, bow, and deposit the bulbs another few inches away, so, unfettered, the plant spreads by “walking” around the garden. I stopped growing it because the flavor was too sharp for me.

The bulbs take root, grow, bow, and deposit the bulbs another few inches away, so, unfettered, the plant spreads by “walking” around the garden. I stopped growing it because the flavor was too sharp for me.

One More, This One Well-Known

One more perennial vegetable, this one familiar to everyone, is asparagus. I don’t understand why anyone who has a garden doesn’t grow asparagus. Even a flower garden, to which asparagus can offer a soft, green ferny backdrop. A bed offers two months of almost daily harvest. Rabbits and deer don’t eat it, so fencing isn’t needed (except in my garden, where my dogs have developed a taste for it).

And pests are rarely a problem. Except for weeds.

Perhaps you’ve been put off by the heroic measures for planting it suggested in older gardening books. That is, digging a deep trench, planting the roots in the bottom of the trench, and then gradually filling it in as the plants grow. Not necessary!

The deep planting suggested was to keep the plants’ crowns beyond the reach of tractors’ cultivator blades. But there’s no reason to cultivate an asparagus bed, and most home gardeners don’t anyway, so make holes just deep and wide enough to cover the roots when planting.

So there you have it, for easy gardening and tasty meals: Plant Caucasian mountain spinach and asparagus, and perhaps, especially if you like the name, Good King Henry.

I MAKE TREES

/6 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichHere are 3 Easy, Fun Grafts I Made Yesterday

Finally, the weather cooperated and I got around to doing some grafting. I could have done it a couple of weeks ago, as I had planned, but I’m blaming cooler weather for the delay. Not that I couldn’t have done it back then, but things chug along more quickly in warmer weather, so I waited.

Apple tree on very dwarfing rootstock

I’m going to describe 3 easy grafts I did yesterday. Which one I chose to do depended on the size of the rootstock on which I was grafting. The scions, which are the varieties I’m grafting on the rootstocks, are all one-year-old stems 6 to 12 inches long and more or less pencil-thick (remember what pencils are?). They have been stored, wrapped to prevent drying out, in the refrigerator so that they are more asleep than the awakening rootstocks.

The principles that make any graft work are all the same. Close kinship of stock and scion. Close proximity of the cambium — the layer just beneath the bark — of the stock and of the scion. All open wounds sealed against moisture loss. And immobilization of rootstock and scion until graft succeeds. My book, The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden, goes into more detail about the why and the how of grafting.

A Tree Make Over

For starters, I turned to the bark graft, good for grafting on rootstocks a couple or more inches across. This first graft was on a Tyson pear tree whose flavor wasn’t up to snuff, so that graft began with doing a Henry the Eighth, lopping off the tree’s head to graft height, which was a couple feet from ground level.

The bark graft comes with an good insurance policy. That’s because onto each rootstock, depending on its diameter, I can stick 3, 4, 5, or even more scions. Only one scion needs to grow, but the more that are grafted, the greater the chance of at least one growing.

I prepared a scion with a bevel cut 2 inches long, at its base, not quite all the way across from one side to the other. On the opposite side of the cut, I nicked off a short bevel.

Then, into the freshly cut stub on the rootstock, I made two vertical slits through the bark, each about 2 inches long and as far apart as the width of the base of the scion.

Carefully peeling back the flap of bark welcomed in the long, cut surface of the scion, putting the cambial layers of rootstock and scion in close contact. This was repeated with the other scions, all around the stub. With the peeled back flaps of bark from the rootstock pushed back up against each inserted scion, one or two staples from a staple gun or a tight wrapping with stretchy electrician’s tape sufficed to hold everything in place.

Finally, I sealed all cut surfaces against moisture loss, for which there are a number of home-made and commercial products. My favorite is a commercial product called Tree-Kote, a black goo that works really well and absorbs sunlight.

Another Tree Make Over, For Smaller Trunks

For smaller rootstocks, say 3/4 inch up to a couple of inches across, there’s the cleft graft. This also comes with an insurance policy, though not as good as that of the bark graft because it only gets two scions per graft. Still, it’s easy so chances for success are high.

At the base of each of the two scions, I made two bevel cuts less than halfway through, each two inches long and not exactly on opposite sides. Viewed head on and from below, the uncut portion was slightly wedge-shaped.

Turning to the rootstock, an older rootstock (OH x F 87), I lopped it off squarely, with a saw, then created a split a couple of inches deep in the middle of the cut surface by hammering a heavy, sharp knife right down into it. After removing the knife, a screwdriver pushed down into the split separated it enough to insert the two prepared scions at each edge of the cleft with their cambiums aligned with the cambium of the rootstock.

Pulling out the screwdriver caused the springiness of the rootstock to close the cleft and hold the scions securely in place. As with the bark graft, all cut surfaces got smeared with Tree-Kote.

And Some Baby Tree Grafts

The whip graft is my graft of choice when rootstock and scion are about the same thickness, pencil-thick. Rootstocks for whip grafts were again OH x F87 pears, this time one-year-old rootstocks, pencil-thick.

I cut at the bottom of the scion with a smooth, sloping cut an inch to an inch and a half long, and made a similar cut at the top of the rootstock.

Holding the sloping cuts against each other and aligning just one edge of each if their diameters didn’t exactly match, I bound rootstock and scion together with a rubber grafting strip. (I’ve also used thick rubber bands, sliced open.)

Wrapping whip graft

As with any graft, cut surfaces must be sealed against moisture loss. Parafilm® helps holds the graft together and seals in moisture. Once my whip graft scions are growing strongly, I’ll cut a vertical slit into the binding to prevent it from choking the plant.

Bark graft, season 3, note flowering

There you have it: 3 easy grafts to make new trees or make over an older tree. Now the excitement begins, watching and waiting for new growth. Sometimes, with that large root system fueling growth, a bark graft scion will grow 2 or 3 feet its first season!