ALL FOR THE FUTURE

/16 Comments/in Gardening, Planning, Vegetables/by Lee ReichSeeding Transplants? Again.

Only a couple of weeks ago I finished planting out tomato, pepper, melon, and the last of other spring transplants, and here I am today, sowing seeds again for more transplants. No, that first batch of transplants weren’t snuffed out from the last, late frost when the thermometer dropped to 28°F on May 13th.

And no, those transplants were not clipped off at ground level, toppled and left lying on the ground, by cutworms. Neither were they chomped from the top down to ground level by rabbits.

I’m planting seed flats today to keep the harvest rolling along right through late autumn.

Future Further

Looking farthest ahead, I have in hand two packets of cabbage seed, Early Jersey Wakefield and Bartolo. Early Jersey Wakefield is a hundred year old variety with very good flavor and pointy heads, due to mature a couple of months after transplanting. Once those heads firm up, they can keep well out in the garden for a few weeks in the cool, autumn weather. Those I set out in spring, once mature, are apt burst open from rapid growth in summer weather. Bartolo yields firm, round heads that store in good condition after harvest, well into winter. They are ready for harvest 115 days after transplanting.

I plan for any of today’s sowings to spend about a month in their containers before being planted out. Cooler weather and lowering sunlight dramatically slow plant growth around here by early October, so any late ripening vegetables need to be ready or just about ready for harvest by then. Bartolo cabbage, with 30 days in a seed flat plus 115 days out in the garden, is then ripe by . . . whoops . . . the END of October! No wonder Bartolo often didn’t ripen for me in the past. (Nothing like writing about my garden to keep me honest and awake. I should re-read the detailed timing schedule I wrote in Weedless Gardening for various vegetables in various climates.)

Okay, all is not lost for winter storage cabbage. Warm weather, timely water from drip irrigation, and soil enriched with plenty of compost might speed maturity along faster than predicted. Unseasonally warm weather through October would also help ripen nearly ripe heads. And there’s always the fallback, with sure-to-ripen Early Jersey Wakefield.

Still on time, guaranteed, will be today’s sowing of Charming Snow cauliflower, maturing 60 days from transplanting.

That’s it, for now, for the cabbage family. Later on in summer I’ll be sowing Chinese cabbage seeds. Perhaps more kale also, although spring sowings of this almost perfect vegetable can carry on right into winter, even spring if the winter is sufficiently mild.

Future Sooner

For sooner use in the coming weeks will be today’s sowings of lettuce, cucumber, and summer squash. I like lettuce but lettuce doesn’t like hot weather and longs days. Those conditions cause leaves to turn bitter as plants send up flower stalks and go to seed. But if I sow a pinch of seeds in flats every couple of weeks, the transplanted lettuce can usually be harvested small, before it’s socked away enough energy and wherewithal to go to seed.

The cucumber transplants I’ll want on hand to replace cucumber plants that I set out a couple of weeks ago. After a few weeks those spring plantings invariably succumb to powdery mildew and cucumber beetles, which not only feed on the plants but also spread bacterial wilt disease. (Easy identification for bacterial wilt, besides a wilting plant, is the thread of bacterial ooze visible as you pull apart a cut stem.)

Summer squash plants also peter out during summer, mostly from, again, powdery mildew, and also from squash bugs and vine borers. If squash vines are covered with soil along their stems, roots will form at the nodes, and the plant will continue production. I’ve got to be careful in saving the older squash plants, though; it’s too easy to have too much of this vegetable.

Memorial Day, Before, During, and After It

Here in the States, the traditional time to plant a vegetable garden, is for some reason, Memorial Day weekend. But that can’t be true from Oregon to Florida and from Maine to Arizona, with our wide variations in climate!

I did put tomatoes, peppers, and plenty of transplants in the ground here during Memorial Day weekend. But I already had sown seeds or transplants of peas, arugula, lettuce, kale, carrots, celeriac before that weekend. And, as I’ve written above, there’s plenty of planting to be done after that date. Memorial Day weekend is not a seminal date in my gardening calendar.

STIRRING MY BLOOD, CLEARING (PARTS OF) THE MEADOW

/10 Comments/in Design, Pruning/by Lee ReichNearing Influence

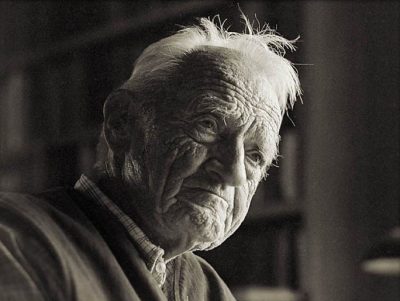

What struck me most about Scott Nearing was his sturdy appearance, arms hanging loosely from broad shoulders, his near perfect teeth, and the deeply creviced wrinkles of his face. He was 91 years old. Looks aside, his influence on me was deep despite the brevity of my visit. Scott Nearing was a professor of economics, a political activist, a pacifist, a vegetarian and an advocate of simple living. And a gardener. For many of these reasons, he was almost a cult figure back in the 1970s when I, a young man, visited him. He was then known mostly for his book Living the Good Life. I had read the book, and decided to drive 1,000 miles from Madison, Wisconsin to show up on his farm, unannounced, in Harborside, Maine.

Scott Nearing was a professor of economics, a political activist, a pacifist, a vegetarian and an advocate of simple living. And a gardener. For many of these reasons, he was almost a cult figure back in the 1970s when I, a young man, visited him. He was then known mostly for his book Living the Good Life. I had read the book, and decided to drive 1,000 miles from Madison, Wisconsin to show up on his farm, unannounced, in Harborside, Maine.

I thought of that visit today as I was swinging my scythe. Would I have been out in the field this morning doing so if I hadn’t made that visit? Scott was a big fan of scything, about which, he wrote, “It’s a first class, fresh-air exercise, that stirs the blood and flexes the muscles, while it clears the meadows.”  For me, working my field in the quiet of early morning, with the sun low in the sky and grasses still moist from morning dew, is sheer pleasure. A morning dance.

For me, working my field in the quiet of early morning, with the sun low in the sky and grasses still moist from morning dew, is sheer pleasure. A morning dance.

From a practical standpoint, no need to worry about waking neighbors with noise of a mower engine, or to worry about getting a mower bogged down in wet spots.

Keeping the Magic

I’ve swung a scythe for many decades. (Not that that makes me an expert in its use; for the first couple of decades I did it wrong. Now, more right.) Two considerations have kept the magic alive.

First, not too much. When I first acquired the acre and a half field to my south, I aimed to keep it a meadow, stemming invasion from woody plants in a natural transition to forest by scything the whole field. Considering the lushness of the vegetation, and how rapidly it grew back, that was a bold undertaking. The result: Something short of sheer pleasure, and tennis elbow.

Salvation came in the form of a small, farm tractor and a brush hog, with which I now mow the bulk of the field once a year.

There’s still plenty to scythe, including areas near my fruit and nut trees, and areas too wet for the tractor. I also scythe selected areas of the field proper, changing yearly to allow scythed sections, whose mowings I gather up, to regenerate. Also important: I limit daily scything to no more than a half hour.

The second consideration is to use the right kind of scythe. The so-called American type scythe, with a curved handle and stamped blade, is put to best use decorating the wall of a barn. I use a so-called Austrian type scythe (purchased from www.scythesupply.com), which usually has a straight handle and is lightweight with a razor sharp, hammered-thin blade. The blade needs periodic hammering (peening) for keeping its taper or for repair, and daily dressing with a whetstone.

Blade length is important. Back when I was working the whole field, the job was made harder because of the 36 inch long blade I was using. Sure, you can cut more with a longer blade, but that was too much lush vegetation to plow through in one swing. Nowadays a 22 inch blade strikes a nice balance, not biting off more than I can “chew.”

No Big Field, No Problem

No need for access to a large field to experience the physical and practical pleasures of scything. For many years, my field was only a portion of my original three-quarter acre property. And no matter how large or small the field, no reason to do as Scott did, to “clear the meadow.” On my small property, I practiced what I called Lawn Nouveau, created, as I detail in my book, The Pruning Book, by sculpting out two tiers of grassy growth. The low grass is maintained just like any other lawn, and kept that way with a lawnmower.

The taller portions need to be scythed but once a year, or more frequently if desired. Raking up mowings from the tall grass portions avoids unsightly clumps or smothering of regrowth. The rakings are good material for mulch or compost. A crisp boundary between tall and low grass keeps everything neat and avoids the appearance of an unmown lawn.

Lawn Nouveau saves me time because the tall grass needs infrequent mowing and there’s no rush to get it done. The tall grass becomes more than just grass as other plant species elbow their way in. Which ones gain foothold depend on the weather, the soil, and frequency of mowing. An attractive mix of Queen Anne’s lace, goldenrod, chicory, and red clover might mingle with the grasses in a dry, sunny area, with ferns, sedges, and buttercups mixing with the grasses in a wetter portion.

Curves at the interface of high and low grass present bold sweeps to carry you along, then pull you forward and push you backward, as you look upon them. Avenues of low grass cut into the tall grass invite exploration — that was the purpose of today’s scything. Thank you Scott.

HOT KNOWLEDGE

/10 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichBetween a Rock and a Hard Place

More knowledge makes for a better gardener. That’s what I had in mind with my most recent book, The Ever Curious Gardener, excerpted here:

With hot weather here today, and soon to be a regular occurance, I pity my plants. While I can jump into some cool water, sit in front of a fan, or at least duck into the shade, my plants are tethered in place no matter what the weather. And don’t think that plants enjoy searing sunlight. High temperatures cause plants to dry out and consume stored energy faster than it can be replenished. Stress begins at about 86 degrees Fahrenheit, with leaves beginning to cook at about 20 degrees above that.

One recourse plants have in hot weather is to cool themselves by transpiring water. Transpiration, which is the loss of water from leaves, can cool a plant by about 5 degrees Fahrenheit. Over ninety percent of the water taken up by plants runs right through them, up into the air, exiting through little holes in the leaves, called stomates. Carbon dioxide and oxygen, the gases plants need to carry on photosynthesis, also pass in and out through the stomates.

All this is fine provided there is enough water in the ground. If not, stomates close, transpiration and photosynthesis stop, and the plant warms. Even if the soil is moist, stomates might close in midsummer around midday if leaves begin to jettison water faster than the roots can drink it in. This situation puts most plants in a bind. Should they open their pores so that photosynthesis can carry on to give them energy, but risk drying out, or should they close up their pores to conserve water, but suffer lack of energy?

CAM at work

Enter cacti and other succulents (all cacti are succulents—that is, plants with especially fleshy leaves or stems—but not all succulents are cacti): their fleshy stems and leaves can store water for long periods. After more than a year without a drop of water, my aloe plant’s leaves still look plump and happy.

Besides being able to store water in their stems and leaves, jade plants, aloes, cacti, purslane, and other succulents have another special trick, Crassulacean Acid Metabolism, for getting out of this conundrum.

Aloe plant, more than a year without water!

They work the night shift, opening their pores only in darkness, when little water is lost, and latching onto carbon dioxide at night by incorporating it into malic acid, which is stored until the next day. Come daylight, the pores close up, conserving water, and the malic acid splits apart to release carbon dioxide within the plant, to be used, with sunlight, to make energy.

I’ve actually tasted the result of this trick in summer by nibbling a leaf of purslane—a common weed, sometimes cultivated—at night and then another one in the afternoon.

Malic acid makes the night-harvested purslane more tart than the one harvested in daylight. Try it.

No CAM? How ‘Bout C4?

Another group of plants, called C4 plants, function efficiently at temperatures that have most other plants gasping for air and water. C4 plants capture carbon dioxide in malate, the ionic form of malic acid, which is a four-carbon molecule, rather than the three-carbon molecule by which most plants—which are “C3”—latch onto carbon.

The enzyme that drives the C4 reaction is so efficient that C4 plants do not have to keep their stomates open as much as do C3 plants. The C4 pathway also does its best work at temperatures that would eventually kill a C3 plant, and cells involved in the various steps are partitioned within the leaf for greatest efficiency.

C4 plants are indigenous to parched climates, but not uncommon visitors in our gardens. Corn is a C4 plant. (Cool climate grains such as wheat, rye, and oats, are C3 plants.)

Looking at my lawn, I see another C4 plant. Hot, dry weather in August drives Kentucky bluegrass, a C3 grass, into dormancy. Not so for crabgrass, a C4 plant, which remains happily green.

I also find some other C4 plants, in addition to corn, in my garden. As many vegetables and flowers flag, all of a sudden lambsquarters and pigweed, both C4 weeds (or vegetables, for those who like to eat them), appear as lush as spinach in spring.

Gardener’s Assistance

Can I do anything to help out my plants in hot weather? Keeping the garden watered helps. (Ways to apply water and how much is needed are all-important, and topics unto themselves.)

Sprinkling or misting plants could keep them cool without their having to pull water up from the soil. But the thirty gallons of water that runs up through a tomato plant in a season, or the fifty gallons that flows through a corn plant, is for more than just cooling these plants. It also carries dissolved minerals from the soil into the plant. So it’s debatable how well a plant would grow with too much misting. And besides, wet plants are predisposed to disease.

A better alternative to sprinkling plants is to grow plants adapted to the climate and the season. My lettuce, spinach, peas, and radishes are doing fine now; despite today’s heat, it’s not really all that hot — yet. And nights are still cool. Mostly, I avoid growing these cool weather plants in summer. Except that I like my lettuce salads, so I extend its season by growing it in the shade beneath trellised cucumbers.

Fortunately, tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, melons, and squashes, although they are neither cacti nor C4 plants, can take quite a bit of heat. They have very deep roots.