THE JOY(S) OF COMPOSTING

Dinosaurs and Snake Eggs, and More

Most benefits of compost are well-known: it takes out your “garbage,” it fertilizes your plants, it’s teeming with beneficial microorganisms, yadda, yadda, yadda. One too often overlooked plus for compost is the thrill of discovery, discovery of things other than compost in the pile.

Discovery might range from the mundane to the sublime. Among the mundane discoveries is that glint of a lost kitchen fork as it emerges from within the chocolatey pile. Same for the favorite vegetable peeler or the lost stainless steel coffee strainer.

More towards the sublime end of the spectrum would be the dinosaur that surfaced as I was turning a pile a few years ago. A dinosaur! Yes, a small, plastic one that got there from who knows where.

More seriously sublime was the clutch of about three dozen soft, white eggs about the size of quail eggs that came into view as my pitchfork lifted a clump of compost for turning into the adjacent compost bin. Turns out they were snake eggs, those of a black rat snake.  Some snakes give birth to live young, ready to crawl; black rat snakes lay eggs.

Some snakes give birth to live young, ready to crawl; black rat snakes lay eggs.

I put a few of those snake eggs into a terrarium along with some compost to see if they would hatch. For the uninitiated (me), it’s an eerie sight to see such a traditionally maligned creature emerge from such a welcome, traditional symbol of springtime rebirth. Baby black rat snakes are not black. Instead, bands of dark and light gray run across their backs.

Another time, while turning my compost pile, I accidentally disturbed a mating pair of black rat snakes in flagrante delicto.

Ducks and Grubs, and More

White grubs occasionally turn up in my pile, but a couple of days ago, one of my piles was home to at least two dozen of the C-shaped, creamy white grubs resting within.  On the chance that they were grubs of Japanese beetles, I started picking them out and yelling “Quack, quack.” No, I hadn’t lost my mind; I was calling the ducks over for a treat of beetle grubs. They dashed for each tossed grub as it hit the ground.

On the chance that they were grubs of Japanese beetles, I started picking them out and yelling “Quack, quack.” No, I hadn’t lost my mind; I was calling the ducks over for a treat of beetle grubs. They dashed for each tossed grub as it hit the ground.

And then a mouse, disturbed in my compost turning, made a dash out of the bin and across the lawn. A mouse in a compost bin is not that surprising, although the construction of my bins and my two dogs are pretty good at keeping mice at bay. (I make efforts to limit mouse populations because they can spread diseases such as hantavirus, salmonella, and lymphocytic choriomeningitis.)

One of the ducks took a break from grub hunting to grab the mouse which, judging from the chase the other ducks gave the lucky duck, is more of a gourmet duck food than even the grubs. Soon only the mouse’s tail was hanging out the duck’s beak, and then the mouse was down the gullet. Here’s a video I took of the Duck eating mouse

But Does Compost Really Need Turning?

You might wonder: What’s with all this compost turning? Each of my compost bins holds a half to three-quarters of a ton of compost, each pile gets turned once, and I have a number of piles. Is it worth all that work?

Turning a compost pile lets me see how the process is chugging along. I keep a record of when a pile was built, and then months later, when it’s turned, how far along it is to being ready to use. After I turn a pile a make a guesstimate of percent decomposition, which is accurate enough for me to know about when it will be ready for spreading.

Turning a pile also lets me get a look at the compost-to-be and then to make any adjustments that might be necessary. I’ll lightly hose down every few inches of turned material, enough to make the ingredients glisten. Anything looking exceptionally dry gets extra water. Occasionally, part of the pile is too wet. I fluff it up as I flip it over into the adjacent bin. Parts of the pile might be compressed into a dense mat. Throwing it into the adjacent bin might be enough to loosen it up; if not, I pick at it with the tines of the pitchfork.

Turning the pile also mixes up the ingredients more than when the pile was built. Each part of the pile, then, gets new neighbors in the form of new ingredients and new microorganisms.

Turning a compost pile is not absolutely necessary, although it’s probably best to leave a bin intact longer if the pile isn’t turned. On the other hand, I find turning a compost pile not only interesting, but also enjoyable and nice exercise.

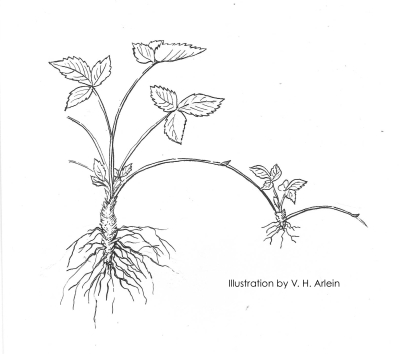

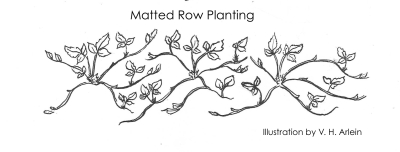

Eventually, plants in a strawberry bed should be 6 to 12 inches apart. The “matted row” system of strawberry planting makes full use of these runners. Plants are set far apart (4 feet between rows and 2 feet between plants) and the spaces between the plants fill in with runner plants which fruit the following season.

Eventually, plants in a strawberry bed should be 6 to 12 inches apart. The “matted row” system of strawberry planting makes full use of these runners. Plants are set far apart (4 feet between rows and 2 feet between plants) and the spaces between the plants fill in with runner plants which fruit the following season.  The matted row is allowed to fill in to a width of 2 feet, and all plants attempting to spread beyond that width are kept in bounds with a rototiller or by hand. With age, that 2 foot ribbon rapidly becomes overcrowded unless old plants are weeded out.

The matted row is allowed to fill in to a width of 2 feet, and all plants attempting to spread beyond that width are kept in bounds with a rototiller or by hand. With age, that 2 foot ribbon rapidly becomes overcrowded unless old plants are weeded out.

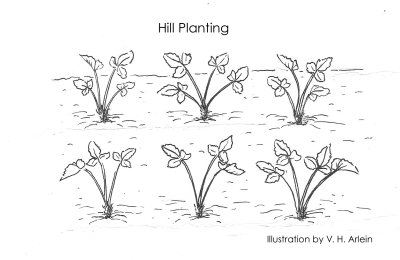

The hill system demands the somewhat tedious job of pinching off all runners through the summer, but the planting stays neater and yields the most berries the first bearing season.

The hill system demands the somewhat tedious job of pinching off all runners through the summer, but the planting stays neater and yields the most berries the first bearing season.

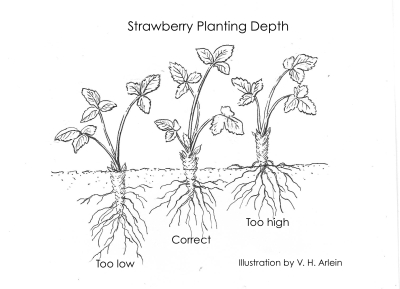

With the roots fanned out by my other hand, the trimmed plant’s roots fit easily into the waiting slit. Planting is completed as I remove the trowel and firm soil against the roots with the heel of my hand.

With the roots fanned out by my other hand, the trimmed plant’s roots fit easily into the waiting slit. Planting is completed as I remove the trowel and firm soil against the roots with the heel of my hand.

Soon the stems will be draped in glossy, green leaves and, a little after that, white flowers that stand proud of the wall on short stalks and glow against their dark backdrop like a starry night.

Soon the stems will be draped in glossy, green leaves and, a little after that, white flowers that stand proud of the wall on short stalks and glow against their dark backdrop like a starry night.

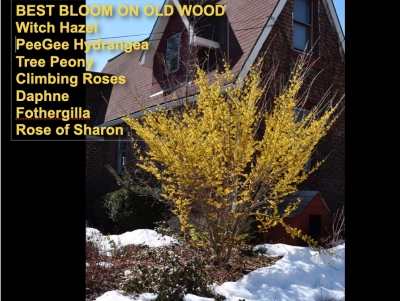

With that said, Panicle Hydrangea develops a permanent trunk or trunks, making it difficult to reach high into its dense head for pruning. No matter, because the plant flowers quite well with little or no pruning.

With that said, Panicle Hydrangea develops a permanent trunk or trunks, making it difficult to reach high into its dense head for pruning. No matter, because the plant flowers quite well with little or no pruning.

That inch depth of compost is the only thing my vegetable beds get each year, and it nourishes closely planted cabbages, tomatoes, lettuces, and other plants from the first breath of spring until cold weather barrels in to shut down production.

That inch depth of compost is the only thing my vegetable beds get each year, and it nourishes closely planted cabbages, tomatoes, lettuces, and other plants from the first breath of spring until cold weather barrels in to shut down production.

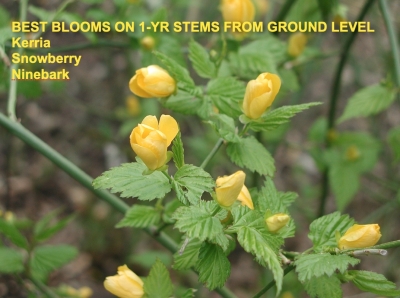

Grouping plants always entails a certain degree of arbitrariness, and because of their disinclination to sucker, a few plants in this category could also be considered “trees,” especially if deliberately trained to one or a few trunks..

Grouping plants always entails a certain degree of arbitrariness, and because of their disinclination to sucker, a few plants in this category could also be considered “trees,” especially if deliberately trained to one or a few trunks..

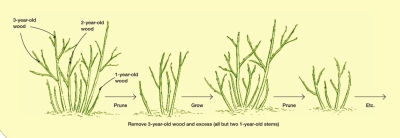

Peer in at the base of the mature plant and you’ll notice wood of various ages growing up from ground level. Begin pruning by cutting away near ground level, some of the very oldest stems. Those oldest stems are also the tallest ones, so these first cuts quickly lower the plant.

Peer in at the base of the mature plant and you’ll notice wood of various ages growing up from ground level. Begin pruning by cutting away near ground level, some of the very oldest stems. Those oldest stems are also the tallest ones, so these first cuts quickly lower the plant.

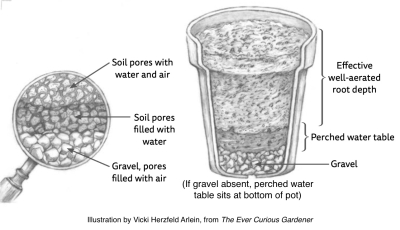

Then I pile up on the floor two gallons each of garden soil, peat moss, perlite, and compost. On top of the mound I sprinkle a cup of lime (except if I’ve sprinkled limestone on the compost piles as I build them), a half cup soybean, perhaps some kelp flakes.

Then I pile up on the floor two gallons each of garden soil, peat moss, perlite, and compost. On top of the mound I sprinkle a cup of lime (except if I’ve sprinkled limestone on the compost piles as I build them), a half cup soybean, perhaps some kelp flakes. I moisten it slightly if it seems dry. When all mixed, the potting soil gets rubbed through a 1/2″ sieve, 1/4” if it’s going to be home for seedlings.

I moisten it slightly if it seems dry. When all mixed, the potting soil gets rubbed through a 1/2″ sieve, 1/4” if it’s going to be home for seedlings.

To the south my meadow ends at a sweep of another neighbor’s field, the more frequently mown grass of which undulate like waves in summer sunshine in contrast to the more upright asters, fleabanes, goldenrods, and monardas that stand upright among the grasses in my meadow.

To the south my meadow ends at a sweep of another neighbor’s field, the more frequently mown grass of which undulate like waves in summer sunshine in contrast to the more upright asters, fleabanes, goldenrods, and monardas that stand upright among the grasses in my meadow.

Besides having its thirst quenched just enough to prevent wilting, it sits in front of a large, unobstructed window facing due south in a room whose temperatures range from the 50s and 60s. (That’s why I’m writing while sitting here in a down jacket!)

Besides having its thirst quenched just enough to prevent wilting, it sits in front of a large, unobstructed window facing due south in a room whose temperatures range from the 50s and 60s. (That’s why I’m writing while sitting here in a down jacket!) The larger the plant, the more roots can be removed. I go around the edge of the root ball with a kitchen knife slicing an inch or two off around the edge of the root ball. That should tell Ms. Fig to chillax!

The larger the plant, the more roots can be removed. I go around the edge of the root ball with a kitchen knife slicing an inch or two off around the edge of the root ball. That should tell Ms. Fig to chillax!