OMINOUS HOUSEPLANTS

Poinsettia Absolved

Sunny temperature reaching the 50s a few days ago enticed me outdoors for pruning. Today, with temperatures in the 20s, I’m back indoors (except for a very pleasant cross-country ski tour earlier) looking over what plants I have, or might have, growing indoors. Their ominous or not so ominous sides.

Mention poisonous houseplants and most people immediately think of poinsettias. Actually, poinsettia’s bad reputation is unfounded. The plant’s not really poisonous. Only a masochist would be able to ingest enough of this foul tasting plant to cause the occasional cases of vomitting that have been reported. This is not to pooh-pooh the toxicity of all houseplants. Many are poisonous.

No sane adult walks around the house plucking houseplant leaves to eat; the greatest danger from poisoning is to children. Ten percent of the inquiries to poison control centers across the nation concern plant poisonings, and the bulk of those inquiries concern children younger than three years. (But in only a small percentage of these cases does the child actually have symptoms of poisonings.)

Common Culprits

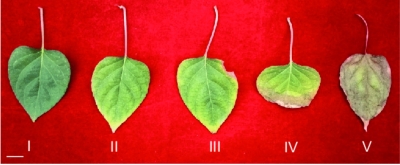

Years ago, I hosted philodendron and dumbcane (Diffenbachia spp.), two very common houseplants, in my home. These two plants are responsible for the first and second most reported poisonings, respectively.

Variegated philodendron

They are in the Araceae Family, a group of plants with needle-like crystals of calcium oxalate in their leaves and stems. When chewed, the crystals cause immediate pain in the mouth and throat, which commonly leads to swelling. This makes speech difficult and is the origin for the common name “dumbcane” for Diffenbachia species. Ingest enough leaves of either plant and vomiting and diarrhea, even death, could follow. Other houseplants in this family include elephant’s ear (Alocasia spp.), flamingo flower (Anthurium spp.), and caladium (Caladium bicolor).

Anthurium

Caladium

The “philodendron” that I grew and many people grow is commonly known as Swiss cheese plant, for its large, holey leaves. Botanically, it’s not a Philodendron, although it was originally classified as one. Now it’s botanical name is Monstera deliciosa. Deliciosa! A poisonous plant? This is one member of the Araceae that bears an edible fruit. The fruit resembles an ear of corn and tastes something like a combination of pineapple and banana. That’s when it’s ripe. Unripe, not so tasty, rich in oxalic acid, and poisonous.

Poinsettias are ranked third as far as the number of reported (not actual) poisonings nationwide. Although poinsettia really is not toxic, it’s a member of the Spurge Family, a family which includes many toxic plants. Guilt by association, perhaps. Members of the Spurge Family contain a milky latex in their sap, and this latex can cause dermatitis. A houseplant Spurge that does warrant caution is the Crown-of-Thorns, which, as long as we are talking about danger to children, also is heavily armed with stout thorns.

Now is the time of year when blooms on forced bulbs carry gardeners through the last leg of winter before spring planting. Most of these bulbs are in the Lily Family,

another family with many poisonous members. The daintiness of Lily-of-the-Valley belies the fact that it contains a potent cardiac glycoside (much like the digitalis found in foxgloves), which even leaches into the water of cut flowers. Hyacinths are wonderfully fragrant, yet also toxic. All parts of sunny daffodils contain lycorine, a toxin that can cause dermatitis with skin contact, and diarrhea and convulsions if ingested.

That toxin, lycorine, also is found in another winter bulb, amaryllis (Hippeastrum spp.), though amaryllis is not in the Lily Family.

And More

A few other houseplants in widely scattered plant families also are worth mentioning for their toxicity. Jerusalem cherry (Solanum pseudocapsicum), a houseplant with brightly colored berries, is in the Deadly Nightshade Family. The family name should tell you something about the plant’s toxic properties. Not all members of the family are toxic in the amounts normally ingested; if so, we’d have to give up eating tomatoes, eggplants, peppers, and potatoes.

Mistletoe is not a houseplant per se, yet it is a plant in the house at Christmas. The white berries, which tend to fall to the ground as the plants dry out, are toxic.

English ivy is a plant that is grown both indoors and outdoors. Unfortunately, its leaves are also toxic.

I don’t like to cast a somber cloud over these houseplants, but it’s important to know which are toxic so as to keep them beyond the inquisitive reach of very young hands. If a child does manage to ingest a plant, save part of the plant for positive identification, and then call a poison control center (http://www.aapcc.org/DNN/). It is not always advisable to induce vomiting, because this can further spread irritating materials.

Now why does an otherwise friendly looking plant — a philodendron, for instance — have to strike a menacing chord with a toxin in its leaves? Inside our homes, overwatering or underwatering probably is the major threat to any houseplant’s existence. But out in the jungle, a philodendron needs some way to ward off a big gorilla who might find the leaves an appetizing salad. In this case, a burning, swollen mouth is a good deterrent.

From an auspicious vantage point, a pear tree glowed like a subdued holiday tree as hints of sunlight’s reds and blues refracted from the natural prisms on the branches.

From an auspicious vantage point, a pear tree glowed like a subdued holiday tree as hints of sunlight’s reds and blues refracted from the natural prisms on the branches.

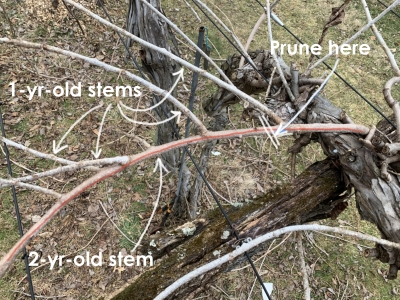

The goals in pruning are to keep the plant reined in to a convenient size for easy harvest, to eliminate enough stems so that those that remain bathe in sunlight and air, and to coax growth of new stems off which will emerge, the following year’s fruiting shoots.

The goals in pruning are to keep the plant reined in to a convenient size for easy harvest, to eliminate enough stems so that those that remain bathe in sunlight and air, and to coax growth of new stems off which will emerge, the following year’s fruiting shoots.

The main challenge with this plant is clearing and separating the almond-sized tubers from soil and small stones.

The main challenge with this plant is clearing and separating the almond-sized tubers from soil and small stones.

So I sowed them in a 4×6 inch seed flat filled with potting soil, then moved the flat in front of a sun-drenched, living room window. Once the lettuce seeds sprouted, which was in a few days, I moved them to the greenhouse. Warmer temperatures are needed to sprout a seed than to grow a plant.

So I sowed them in a 4×6 inch seed flat filled with potting soil, then moved the flat in front of a sun-drenched, living room window. Once the lettuce seeds sprouted, which was in a few days, I moved them to the greenhouse. Warmer temperatures are needed to sprout a seed than to grow a plant.

I use this same method to keep up a steady supply of lettuce and other seedlings all through summer, the plants typically needing about a month in the

I use this same method to keep up a steady supply of lettuce and other seedlings all through summer, the plants typically needing about a month in the

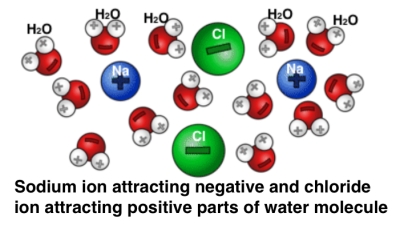

What happens when water enters the picture? A water molecule, because of its shape has a slightly imbalanced charge distribution. The negatively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the sodium ion of table salt, and the positively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the chloride ion.

What happens when water enters the picture? A water molecule, because of its shape has a slightly imbalanced charge distribution. The negatively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the sodium ion of table salt, and the positively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the chloride ion.

My favorite treatment for icy conditions here at home is spreading wood ash. Effectiveness comes from the dark color absorbing sunlight to speed melting, a slight grittiness increasing traction, and its salt content. Of course, access to wood ash means you or an ash-rich friend burns wood for heat.

My favorite treatment for icy conditions here at home is spreading wood ash. Effectiveness comes from the dark color absorbing sunlight to speed melting, a slight grittiness increasing traction, and its salt content. Of course, access to wood ash means you or an ash-rich friend burns wood for heat.