THE BEST HERB FOR A NORTHERN WINTER

Calamity Avoidance

A horticultural calamity averted. Again. Deb was snipping some leaves from our potted rosemary “tree” for salad dressing and said she noticed that the plant looked a little wilty. I was skeptical. Rosemary leaves are so narrow and stiff that they hardly broadcast their thirst. Still, quite a few rosemary plants have succumbed to winter drought here.

I checked the plant and, in fact, the leaves did look a bit wilty. The probe of my sort-of-accurate electronic moisture tester (which I nonetheless highly recommend) confirmed Deb’s diagnosis. The soil was very dry but, luckily, not to the point of killing the plant.

Allow me to digress . . . Soil scientists represent soil moisture levels with four descriptors. Right after a thorough watering, a soil is “saturated,” with all pores filled with water. Saturation is not desirable in the long term because roots need to “breathe” to do their work of drawing in nutrients and water, which is why plants exhibit the same symptoms from either dry or sodden soil.

Without additional water, gravity begins to pull water down and out of the larger pores of a saturated soil. Once gravity has pulled all the water it can from a soil, the soil is at “field capacity,” much to the pleasure of resident plants. At this point, large pores are filled with air yet some water, which is available for plants, is retained within smaller pores and clinging to soil particles.

Roots continue to slurp more and more water from the soil, but with increasing difficulty because water within even smaller pores and clinging even closer to soil particles is increasingly tightly held there by capillary attraction. Although the soil has moisture, it’s mostly inaccessible to plants. “Wilting point” has been reached.

Eventually, the only moisture left in the soil is that held very tightly in the very smallest pores and pressed tight against soil particles. That’s “permanent wilting point” from which, as the name implies, there’s no turning back. The plant will die.

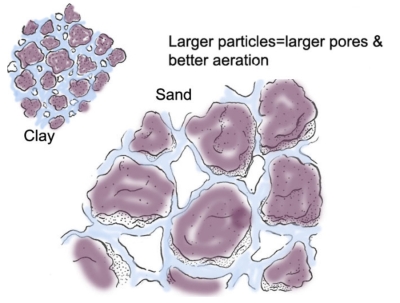

The actual amount of water in a soil at any of these stages depends on the range of particle sizes in the soil. Clay soils have tiny particles, with tiny spaces between them, so have more water at wilting and permanent wilting point than do sandy soils, with their large particles and large pores.

At or near field capacity, sands have more air and less water than clays.

Where were we? Oh, my rosemary plant. I’m figuring it was just teetering on the edge of wilting point. Needless to say, I watered both my rosemary “trees.”

(For a lot more about soil water and how to make the best of it, see my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden.)

Dry Air, Moist (Enough) Soil

You’d think — I once did — that rosemary, because in the wild it billows down dry hillsides overlooking the Mediterranean, would be resistant to drought. It does tolerate dry air. But those wild plants’ roots are in the ground where they can forage far and wide for moisture; not so in a pot.

Also, my rosemary plants are coddled with relatively consistent warmth in winter and a potting mix rich in nutrients. Couple this with low light conditions, even near a south-facing window, and you get very succulent growth. I don’t know what rosemary plants growing on a Grecian hillside are doing now, but my plants are growing like gangbusters. All that succulent growth transpires lots of water, and is very susceptible to drought.

Left half of this rosemary expired last summer

Once my plants go outdoors in summer, their leaves mature and toughen and growth is less succulent. They do still need sufficient moisture, so I have drip tubes on a timer quenching their thirst (and that of other plants). Except, that is, when the timer’s battery needs replacing and I don’t notice it. That was last summer. The plants were not at the permanent wilting point but a number of branches, which I pruned off, dried up, dead.

In Praise of Potted Rosemary

All this is not to frown upon growing rosemary where it can’t survive winters outdoors. On the contrary, I consider rosemary to be the finest herb for indoor growing. Flavorwise, it packs a powerful punch, unlike chives, for example, a plant that needs to be practically decimated if you really want to flavor something with it. Merely brushing against my rosemary plant releases an aromatic, piney cloud.

Rosemary is also a very attractive houseplant whether grown as a scraggly shrub reminiscent of the wild plants in their native haunts, trained as dense cones, or — as are my plants — as miniature trees. The leaves retain a healthy, verdant look, unlike those of basil, which look sickly and out of their element in dry, relatively dark and cool homes in winter.

Rosemary also rarely suffers from any insect or disease problem.

And finally, properly cared for, rosemary is perennial so can provide aroma, flavor, and beauty for many, many years.

But you and I do need to pay close attention to watering.

Rosemary, with its compatriots, bay and citrus, in summer

How interesting, and I just love rosemary, too.

It’s my understanding that some or maybe all plants might survive in winter outside, as in a greenhouse, but will be dormant at our latitude from about mid-November to mid-March, from insufficient day length. I learned this the hard way by letting my chickens out often one warm winter, and they decimated the grass, as it didn’t grow back.(They had fun, tho.) Anyway, is the light in your house sufficient to extend the “day” for your indoor rosemary? Or does that scientific principle apply here? Much appreciated.

No comprendo “outside, as in a greenhouse.” Light intensity and photoperiod are sufficient to keep rosemary alive and well in winter in a house. Irrespective of light, rosemary will not survive without lots of protection outdoors here in zone 5. But why not keep it indoors, in the house; it’s pretty, fragrant, and flavorful.

Very interesting! Would you mind sharing how you trained it to grow as a tree?

Here’s a much shortened version of what I wrote in my book, THE PRUNING BOOK. (It was also accompanied by step by step photos).

Start with a the rooted cutting. For any standard-to-be, it is important to provide excellent growing conditions for vigorous growth in developing the main stem. And you will allow only one main stem—the trunk-to-be—to develop. Set a stake in the soil and tie the growing stem to the stake every few inches. Keeping the stem upright and straight does more than just create a straight trunk. Upright growth is inherently most vigorous and naturally suppresses the growth of lower shoots—just what you want in the developing standard.

Diligently remove any shoots growing up near ground level, as well as those growing out along the stem. Once the main stem — the trunk-to-be — reaches full height, it is time to form the mop head. The ideal length of the trunk is going to depend, artistically, on the density and size of the leaves, and, physiologically, on the vigor of the plant.The thin, dense leaves of my rosemary look just right filling the 8-in. wide ball capping an 12-in. long trunk. (At three years old, it is indeed a trunk!)

Begin forming the head by pinching out the growing point of the main stem. This pinch takes out the top bud, which made hormones that inhibited growth of lower buds. The most vigorous new shoots will be those developing near the top of the main stem, and that’s where you want them. Create a dense head, now, by pinching those shoots after every few inches of growth. Keep cutting away any branches or leaves sprouting lower down along the trunk.

Thank you! I will check the book out as well!

Thanks for the clear description of soil moisture levels. I’ll use it next year in training new master gardeners.

Hello, Lee. Thanks for info on rosemary. I’m in northern Westchester and have been keeping my fairly mature and large potted rosemary outdoors year-round. I ‘bury’ its pot in another container half-filled with soil and build up more soil around it up to the top of the larger container. I then mulch it like crazy with clean cut straw and cover it with a plastic bag with holes in it. Much to my delight it has survived and thrived for two, going on three (fingers crossed) winters. We’ll see…

I have another question, though. I would like to buy and keep a bay leaf plant indoors. Do you have a recommended source where I could order one? And how do you treat your bayleaf? Indoor winter/outdoor warm months, much like your rosemary? Thanks again for sharing your wisdom, I’m most grateful!

Mary

I treat my bay laurel the same as the rosemary, except in a bigger pot and keeping an eye out for scale insects.

Thanks as always Lee. My two indoor rosemary plants teeter between too dry and too wet. This post was very helpful.

What is the name/brand of the soil meter you are using?

I had hoped mine would be accurate but have found most recent readings of fully saturated soil contradicted by wilted appearing plants and bone dry soil on inspection. There was mention in the instructions of gently roughing up the probe prior to testing to remove an oxidized outer layer that could lend to false readings. My scrubbing was to no avail. I also am not storing the meter in the pot (as instructed).

I am currently trialing ‘Madeline Hill’ Rosemary in my zone 6 garden. I have tried many ‘Hardy’ types in the past with varying success. I was pleased to see my local experts at MOBOT growing the same variety in their outdoor trial garden surviving into year 2 or 3. Not sure if this would be hardy to your zone 5 but thought I would mention it.

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B07RDDLCBJ/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_search_asin_title?ie=UTF8&psc=1, with similar items available at most garden centers. It seems like the probe you had was just defective. I’ve had a few electronic moisture probes; they all worked decently well and none needed “roughing up.”

I doubt any rosemary would be top hardy in zone 5.

I buy a rosemary plant every spring, nurture it through the summer, and bring it indoors in late fall. Invariably, the plant dries up and dies. I still can’t figure out if I’m overwatering it or under watering it.

From what you write, I’d say underwatering. When you water, do so until water runs out the bottom of the drainage hole. Right after you give the plant a thorough watering, let excess water drain away, and then lift the pot to osee how heavy the well watered pot feels. Then you’ll know when watering is needed. Or get one of those inexpensive electronic moisture probes. https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B07RDDLCBJ/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_search_asin_title?ie=UTF8&psc=1, with similar items available at most garden centers.

I have had problems with spider mites on indoor rosemary quite often. I keep a sharp eye out and give them a shower under and on top of the leaves now and then. I do live in a warmer climate where bugs stay alive all year round.

Spider mites are associated with dry air, so that showering is good, or anything that you can doo to increase the humidty.

What is the “sort-of-accurate electronic moisture tester” that you highly recommend?

Thanks!

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B07RDDLCBJ/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_search_asin_title?ie=UTF8&psc=1, with similar items available at most garden centers.

I have frequently told people the biggest cause of Rosemary death in the winter is drying up. I remind people when the soil is dry to water and water well. They don’t like wet roots but can’t take dry conditions. Too many people say to keep Rosemary dry, they don’t like to be wet. Instant death!!!!

All true!!

Had Rosemary in a NW WA. garden. Must have liked all the rain we get as it got huge. M. Green

Just as long as soil drains well.

Thanks Lee! This article comes at the perfect time for our wilting rosemary!

Glad it helped, if it did (in time),Amy

Can you clarify what you mean by “succulent growth”?

I’ve started all my rosemary from seed and have always kept them in pots so I can bring them inside in winter months.

All I’ve done, ever, is water them when the soil is dry about 1” below surface. And I keep them next to other plants, which I think helps them share humidity, etc.

By succulent growth I mean soft, sappy growth, with relatively wide spaces from leaf to leaf. Very bright light, cooler temperatures, and an excess of neither water nor fertilizer makes for the opposite.

Good explanation of soil conditions. I always wondered though, how a plant can thrive in a vase of water with no soil – for ex. philodendron? Thanks in advance.

Good question. Water does contain some dissolved oxygen, for awhile at least. Roots that develop in water are different from those that develop in soil. Transferring a plant from water to soil must be done carefully. For an excellent article about water roots and their ramifications, see https://www.yourindoorherbs.com/differences-between-soil-roots-water-roots/. Water is oxygenated for hybdroponically grown plants.