MOVING ALONG, INSIDE AND OUT

Figs Awakening

Even in the cool temperature (45 degrees Fahrenheit) and darkness of my basement, the potted figs can feel spring inching onward. Buds at the tips of their stems have turned green and are just waiting for some warmth to burst open. Or, if the plants just sit where they are long enough, the buds will unfurl into leaves and shoots. Which would not be a good thing.

My goal is to keep the plants asleep long enough so that they can be moved outside when they will no longer be threatened by cold temperatures. How much of a threat temperatures pose depends on how much asleep the plants are. Fully dormant, a fig tree tolerates temperatures down into the low 20’s. Even now, as they are just barely awakening, they can probably laugh off temperatures into the mid-20s.

If the buds expand into shoots and leaves, they’ll be burned by any temperature below freezing. And especially so if those new shoots and leaves get started indoors, where warm temperatures and relatively low light makes for overly succulent growth. Bright sunlight, even without freezing temperatures, can then cause damage.

Fig plants that start growing in earnest indoors get presented with two options. The first is to get them to the sunniest window in the coolest room so that growth is more robust, then move them outdoors after any threat of frost has passed — about the same time as tomato transplants get planted out. (Around here, that’s about the third week in May.)

The second option is to move them outdoors as soon as temperatures won’t again fall below the mid-20s. Temperatures below 32 will burn the succulent, new shoots and leaves, but plants will push forth new growth well-adapted to the great outdoors. If an Arctic blast is predicted, with lower that usual temperatures — that is, below about 25 degrees Fahrenheit — the plants need to be moved temporarily to the garage, mudroom, or other convenient shelter.

Different Strokes For Different . . . Figs

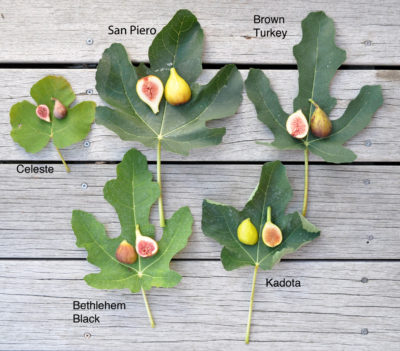

A fig’s treatment depends on the variety. Genoa, Excel, and Ronde de Bordeaux are three new varieties that I hope to taste this summer. They’ll get first-class coddling: Moved outside soon, then put into temporary shelter at the slightest hint that damaging temperatures could arrive. I might just put the others outside, and leave them there.

The Kadota fig gets planted, in its pot, right in the ground. Its roots will grow out through all the holes I drilled in the side and bottom of the pot so the plant becomes self-supporting, waterwise, until fall. I’ll plant it out soon, even though once it’s planted, it’s staying put all season long. (I have a backup plant.)

Too Weird To Eat

Moving forward into spring — on into late spring — brings dogwoods into bloom. Blossoms of our native flowering dogwood (Cornus florida) will soon be followed by those of kousa dogwood (C. kousa), and also called Japanese or Korean dogwood), native to east Asia.

The flowers of both species are very small and pretty much green. “Not so!,” you say, thinking back to last spring’s show of large white or pink petals. Those large white or pink things are, in fact, not petals, but bracts, which are modified leaves that, admittedly, serve pretty much the same function as petals, that is, to look pretty, attract pollinators, etc.

Over the years, the spring show from flowering dogwoods has become sparse because of powdery mildew and other diseases. Which is why kousa dogwood, which is disease resistant, has been increasingly planted.

Flowering dogwood can have either pink or white flowers — whoops, I mean bracts. Until recently, kousa dogwood came only in white. But now, breeders at Rutgers University, after decades of work, have introduced Scarlet Fire kousa dogwood, a cold hardy (Zone 5 to 8), disease resistant variety bearing pink bracts.

The flowers of kousa dogwood, whether pink or white bracted, are followed by edible fruits. The round fruits are the size of a quarter, dark pink, and very weird-looking. To me, they look like water (naval) mines, not a very friendly association for a fruit. Their appearance has also been described as that of a sea urchin shell, also not very gustatory. Inside, the flesh is sweetish and mealy, something like a cross between mango and pumpkin — not my two favorite flavors, but even if they were, those dark pink water mines are too off-putting in appearance for me to more than sample them (just so I could report on their flavor).

Still, kousa fruits add to the show from the flowering bracts and the healthy foliage.

Temperatures stay relatively consistent and cool (40-45°F.) in my basement and it’s dark down there, so the plants generally stay dormant until sometime, probably next month, when I can set them outside. Keeping the plants slightly on the dry side also helps hold back growth.

Temperatures stay relatively consistent and cool (40-45°F.) in my basement and it’s dark down there, so the plants generally stay dormant until sometime, probably next month, when I can set them outside. Keeping the plants slightly on the dry side also helps hold back growth.