SENSUAL THINGS, AND WATER

Heady Nights

It’s difficult to work outside in the garden these days, especially in early evening. No, not because of the heat. Not because of mosquitos either. The difficulty comes from the intoxicating aroma that wafts into the air each evening from the row of lilies just outside the east side of my vegetable garden.

These aren’t daylilies, which are mildly and pleasantly fragrant. Wild, orange daylilies are common along roadways and yellow and hybrid daylilies, often yellow, are common in mall parking lots. (That’s not at all a dis’; the plants are tough and beautiful, and I’ve planted them also.) They’re also not tiger lilies, which lack aroma and sport downward turned, dark red speckled orange flowers with recurved petals.

My fragrant lilies are so-called oriental hybrid lilies, which are notable for their large flowers and strong fragrance. My favorite among those I grow is Casa Blanca. The flowers are large and lily white (what’d you expect?) except for the threadlike, pale green stamens emerging from their centers, with dark red anthers capping their ends.

Casa Blanca would be worth growing just for the look of the flowers; the fragrance, very sweet and very heady make this bulb a must-grow. Not for everyone, though. A few people dislike this fragrance. For some people it’s more than just stinkiness, the aroma causing nausea, dizziness, or congestion.

Casa Blanca’s stems can rise to about four feet tall, their upper portions circled with almost a dozen of those large blossoms in various stages of ripening. Some years, staked, persimmon orange, Sungold tomatoes grow in that bed, and the tomato and lily plants looked very pretty mingling together. (Tomatoes were, after all, once grown as ornamentals.)

This year I’m growing kale in that bed which, besides good eating, provides a frilly base from which the lily stems rise.

In Good Taste

Turning to another of the senses . . . taste. Blueberries. They are among my most successful fruits and, as usual, the plants’ stems are bowing to the ground under a heavy load of berries this time of year.

Not to brag, but the average yield of a blueberry bush is 3 to 5 quarts. My blueberry bible, Blueberry Culture (1966), states that “proper cultural practices can increase the yield to as much as 25 pints per bush.” I average about 18 pints per bush, with some bushes yielding as much as 24 pints. Organically grown, of course.

I credit my good yield to periodic additions of sulfur to maintain acidity of pH 4.0-5.5, timely watering with drip irrigation especially the plants’ first few years, topping up of existing wood chip, wood shavings, or leafy mulch each fall with an additional 3 inch depth of any organic, weed-free mulch, and pruning every spring.

In year’s passed, I also added soybean meal for extra nitrogen to fuel stem growth. Blueberry flower buds develop along growing stems, with flowers open along those stems the following spring. More stem growth means more blueberries, to a point. For many years I have foregone soybean meal because the the plants were overly vigorous, creating a dense jungle that makes getting to the berries too difficult.

One other key to success and topnotch flavor is a net during the summer to fend off birds and — for best flavor — careful picking of only dead ripe fruits.

Water, Too Much or Too Little

So far, the growing season here in the Northeast has been one with both dry spells and wet spells, more than usual of each. Some recent thunderstorms fool many a gardener into thinking that the soil has been thoroughly wetted. But such rains are often only a drop in the bucket.

The only way to know for sure if enough rain has fallen for plants to really slurp up water is to check the soil or measure the actual amount of rainfall. A friend tells me he waters his plants every day. Every day! How much? It could be too much or too little, and probably is one or the other. I like to quantitate things so I measure rainfall or watering, as well as soil moisture, in a few different ways.

First, measuring water added to the soil: The ideal is about a 1 inch depth of water per week, which is equivalent to about a half a gallon per square foot of surface area. For hand watering a young tree, with an estimated root spread of only a couple of square feet, I fill the watering can with a gallon of water and sprinkle it on.

Rainfall, or the water from a sprinkler, could be measured with a straight-sided container. I use a rain gauge whose tapered body can break down the measurement into tenths of an inch, readable from indoors.

Digital moisture probe.

I usually measure the actual moisture in the soil with a handy little meter attached to a probe that slides a half a foot down into the soil. As expected, the meter told me today that the soil is very wet. Not surprising after 3 inches of rainfall, as measure in the rain gauge, two nights ago.

(There’s more about blueberries and water in my books Grow Fruit Naturally and The Ever Curious Gardener.)

The blueberries with which I am most familiar are those that I grow, which are highbush blueberry and lowbush blueberry. I grow blueberries because they are beautiful plants, because they are relatively pest free, because they are delicious, and because they fruit reliably for me year after year.

The blueberries with which I am most familiar are those that I grow, which are highbush blueberry and lowbush blueberry. I grow blueberries because they are beautiful plants, because they are relatively pest free, because they are delicious, and because they fruit reliably for me year after year.

After a few years of watching the weakened plant recover each season, I made cuttings from some of the stems. The cuttings rooted and the new plants, rather than being grafted, were then growing on their own roots. Even a cold winter wouldn’t kill the roots, living in soil where temperatures are moderated. If the stems died back to ground level, new sprouts would still sport those dark, red blossoms.

After a few years of watching the weakened plant recover each season, I made cuttings from some of the stems. The cuttings rooted and the new plants, rather than being grafted, were then growing on their own roots. Even a cold winter wouldn’t kill the roots, living in soil where temperatures are moderated. If the stems died back to ground level, new sprouts would still sport those dark, red blossoms.

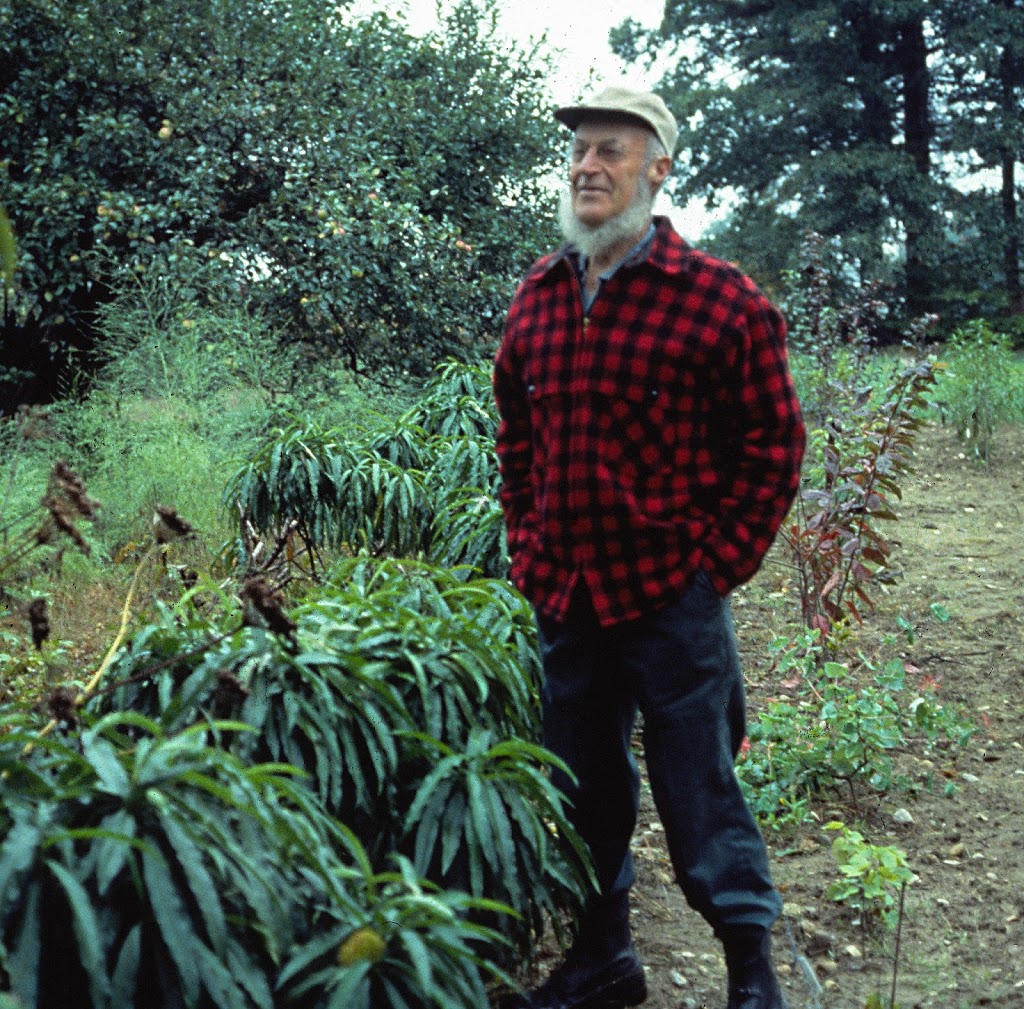

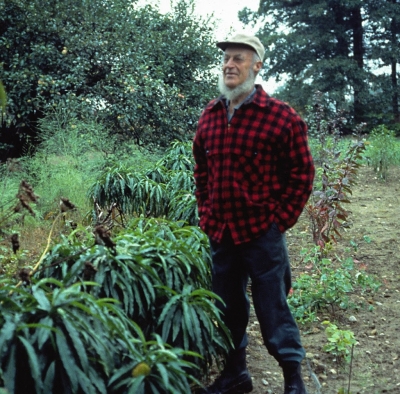

Putting up the net always brings the words of fruit breeder Dr. Elwyn Meader to mind. When I visited him back in the 1980s, the old New Englander, still active in his retirement and growing about an acre of blueberries, among other crops, recounted in his slow, New Hampshire accent, “It takes a patient man to net an acre of blueberries.” Covering my two plantings encompassing a total of about a thousand square feet always creates a little tension.

Putting up the net always brings the words of fruit breeder Dr. Elwyn Meader to mind. When I visited him back in the 1980s, the old New Englander, still active in his retirement and growing about an acre of blueberries, among other crops, recounted in his slow, New Hampshire accent, “It takes a patient man to net an acre of blueberries.” Covering my two plantings encompassing a total of about a thousand square feet always creates a little tension. I now feel like a captain setting sail on an old sailing vessel, with all the sails trim and masts set. Except rather than sails and masts, it’s a blueberry net that’s spread tightly over the permanent, 7-foot-high perimeter of locust posts and side walls of anti-bird, plastic mesh. That netting covers 16 bushes within a 25 foot by 25 foot area. Rebar through holes near the tops of the locust posts keeps that side wall mesh taught and 18” high chicken wire along the bottom keeps rabbits, which love to teethe on that plastic mesh, from doing so.

I now feel like a captain setting sail on an old sailing vessel, with all the sails trim and masts set. Except rather than sails and masts, it’s a blueberry net that’s spread tightly over the permanent, 7-foot-high perimeter of locust posts and side walls of anti-bird, plastic mesh. That netting covers 16 bushes within a 25 foot by 25 foot area. Rebar through holes near the tops of the locust posts keeps that side wall mesh taught and 18” high chicken wire along the bottom keeps rabbits, which love to teethe on that plastic mesh, from doing so. Don’t worry about the birds. They get their fill of berries elsewhere. I don’t net my lowbush blueberries, nor my mulberries or gumis. Birds don’t usually share the mulberries or gumis with me. This year, for some reason, they are sharing.

Don’t worry about the birds. They get their fill of berries elsewhere. I don’t net my lowbush blueberries, nor my mulberries or gumis. Birds don’t usually share the mulberries or gumis with me. This year, for some reason, they are sharing. Juneberries are related to apples and pears, not blueberries, and share some of their kin’s pest problems. Especially in my garden. They’re one fruit that didn’t grow well for me so, years ago, I finally dug the plants up.

Juneberries are related to apples and pears, not blueberries, and share some of their kin’s pest problems. Especially in my garden. They’re one fruit that didn’t grow well for me so, years ago, I finally dug the plants up.