From Alaska & the White Mountains to my Garden

Lingonberry a plant of harsh, cold climates. I’ve seen the plants poking out of rocky crevices in Alaska and high in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, all of which makes all the more surprising the stellar performance of my plants in this hot summer. For years they sat quietly, growing slowly and slowly spreading; this summer, the plants took off, their underground stems reaching further than usual and aboveground stems sporting a very respectable crop. Or, I should say, crops, plural; more on that later.

Here in the U.S., lingonberries are little known and, when they are known, it’s as jars of jam. But merely utter the word “lingonberry” to someone Scandinavian and watch for a smile on their lips and a dreamy look in their eyes. Each year, thousands of tons of lingonberries are harvested from the wild throughout Scandinavia, destined for sauce, juice, jam, wine, and baked goods. A fair number of these berries are, of course, just popped posthaste into appreciative mouths.

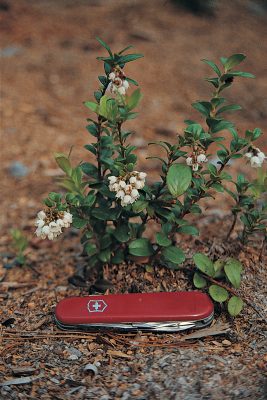

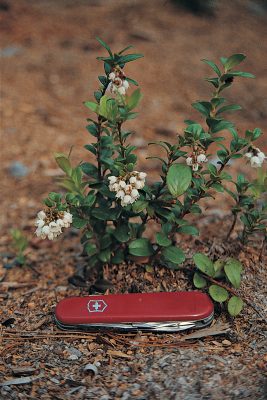

Lingonberry in White Mountains

Lingonberries have often been compared to their close relative, our Thanksgiving cranberries. But lingonberry fruits meld just enough sweetness with a rich, unique aroma so that the fruits — if picked dead ripe — are delicious plucked right off the plants into your mouth or mixed with, say, your morning cereal. As far as I’m concerned, cranberries are never palatable until doctored up with plenty of sugar and heat.

More Than Just Good Looks

As tasty as lingonberry is, I don’t grow it only for its fruit. Lingonberry also outshines its stateside relative in looks. The plants are pretty enough to have garnered a rating of 3, the highest possible, in my book Landscaping with Fruit.

Like cranberry, lingonberry grows only a few inches high and spreads horizontally to blanket the ground with evergreen leaves the size of mouse ears. While the onset of cold weather in fall turns Thanksgiving cranberry’s evergreen leaves muddy purple color, lingonberry leaves retain their glossy, green appearance, like holly’s, right through winter.  Lingonberry could stand in well for low-growing boxwood — in a parterre, for example, a use first suggested in 1651 by André Mollet, the French gardener to Queen Christina of Sweden

Lingonberry could stand in well for low-growing boxwood — in a parterre, for example, a use first suggested in 1651 by André Mollet, the French gardener to Queen Christina of Sweden

Cute, urn-shaped blossoms dangle singly or in clusters near the ends of lingonberry’s thin, semi-woody stems. These urns hang upside down (upside down for an urn, that is) and are white, blushed with pink. They’re not the kind of blossoms that are going to stop street traffic, but are best appreciated where plants can be looked at frequently and up close — such as in the beds along the path to the front of my house.

If you miss the spring floral show, you get another chance because lingonberries blossom twice each season. That second show has now morphed into clusters of developing fruits that hang right next to clusters of fruits ripening from the first round of blossoms. Fruit yields are greater from the second flowering than from the first.

The pea-sized fruits a show in themselves, the bright red berries hanging on the plants for a long time, well into winter. Backed by the shiny, green leaves, they making a perfect Christmas season decoration in situ.

Soil Prep & Management: Obligatory but Easy

Lingonberry plants do need some special care. Hot summer temperatures aren’t ideal. My plants were originally near the east and north sides of my house. Those on the east side are now few and far between, perhaps helped along on the way out by the scratching of the ground beneath them by my chickens, now gone (replaced by ducks, who don’t scratch). The north side of the house, not as welcoming to the chickens because it’s my dogs’ hangout, is, of course, cooler.

All the soils that lingonberries naturally inhabit have good drainage and are extremely rich in humus (decomposed organic material), which clings to moisture. In addition to good drainage and abundant organic matter, lingonberries enjoy the same very acidic conditions — with a pH ideally between 4.5 and 5.5 — required by blueberries, mountain laurel, rhododendron and other kin in the Heath Family. These conditions are easily reproduced in a garden.

I created my bed of lingonberries, which is also home to lingonberry kin, by first checking the soil pH. If the pH is too high, digging elemental sulfur into the top six inches of ground can make it right. Three-quarters of a pound per 100 square feet in sandy soils, or 2 pounds per 100 square feet in heavier soils will lower the pH by one unit. Where soils are naturally very alkaline (pH higher than 8), such as in many parts of the western United States, soil needs to be excavated at the planting site and replaced with a fifty-fifty mix of peat moss and sand. Alternatively, this mix could go into containers plunged into the ground up to their rims. In wet areas, build up mounds of soil and peat, and plant the lingonberries on the mounds, which keeps their shallow roots above water level.

I set my plants at two foot by two foot spacings which plants fill in to form a solid mat over the ground.  Every year, in late fall, I scatter wood chips, sawdust, or shredded leaves over the plants, enough for an inch or two depth. Sifting down through the leaves and stems to keep the ground cool and moist, to prevent frost from heaving plants in winter, to maintain high humus levels in the soil, to provide some nutrients, and to buffer soil acidity. Every few years I check acidity, and sprinkle sulfur on the soil, as needed.

Every year, in late fall, I scatter wood chips, sawdust, or shredded leaves over the plants, enough for an inch or two depth. Sifting down through the leaves and stems to keep the ground cool and moist, to prevent frost from heaving plants in winter, to maintain high humus levels in the soil, to provide some nutrients, and to buffer soil acidity. Every few years I check acidity, and sprinkle sulfur on the soil, as needed.

Enjoy!

Beyond needing mulching and having their soil acidity monitored, lingonberries are carefree plants. My main “job” is harvesting the berries. No need even to rush picking or eating them. They keep well on or off the bush, in part because they contain benzoic acid, a natural preservative. Refrigerated, the harvested berries keep for at least eight weeks. In nineteenth-century Sweden, lingonberries were kept from one year to the next as “water lingon,” made by merely filling a jar with the berries, then pouring water over them.

My main problem with lingonberries is, at the end of the growing season, deciding whether to harvest and enjoy the berries immediately and enjoy only the glossy, green groundcover or whether to leave the berries on into winter and enjoy the look of the glossy green groundcover livened up with red berries. Or to split the different, occasionally harvesting some of the fresh berries all through winter.

Lingonberry and lowbush blueberry in fall

of how fig fruits develop and grow, and ways that ripening can be hastened along helps soothe my affliction.

of how fig fruits develop and grow, and ways that ripening can be hastened along helps soothe my affliction.

Very important: Don’t try this on a fruit very far from ripening, which is, of course, hard to tell until the fruit starts ripening. But if you really love your fig tree, you’ve been staring at it a lot. As you do so you’ll begin to notice subtle changes. I’ve typically used this method towards the end of the growing season when fig ripening slows with waning sunlight and cooling temperatures.

Very important: Don’t try this on a fruit very far from ripening, which is, of course, hard to tell until the fruit starts ripening. But if you really love your fig tree, you’ve been staring at it a lot. As you do so you’ll begin to notice subtle changes. I’ve typically used this method towards the end of the growing season when fig ripening slows with waning sunlight and cooling temperatures.

Lingonberry could stand in well for low-growing boxwood — in a parterre, for example, a use first suggested in 1651 by André Mollet, the French gardener to Queen Christina of Sweden

Lingonberry could stand in well for low-growing boxwood — in a parterre, for example, a use first suggested in 1651 by André Mollet, the French gardener to Queen Christina of Sweden

Every year, in late fall, I scatter wood chips, sawdust, or shredded leaves over the plants, enough for an inch or two depth. Sifting down through the leaves and stems to keep the ground cool and moist, to prevent frost from heaving plants in winter, to maintain high humus levels in the soil, to provide some nutrients, and to buffer soil acidity. Every few years I check acidity, and sprinkle sulfur on the soil, as needed.

Every year, in late fall, I scatter wood chips, sawdust, or shredded leaves over the plants, enough for an inch or two depth. Sifting down through the leaves and stems to keep the ground cool and moist, to prevent frost from heaving plants in winter, to maintain high humus levels in the soil, to provide some nutrients, and to buffer soil acidity. Every few years I check acidity, and sprinkle sulfur on the soil, as needed.

Actually, it’s more of a challenge to me because the plant tolerates scale reasonably well. Once moved outdoors in spring, the plant soon recovers from the attack and its resident scale population, either from the changed environment or from predators, subsides.

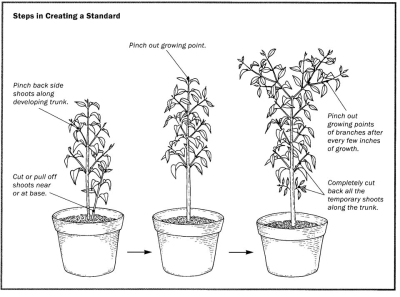

Actually, it’s more of a challenge to me because the plant tolerates scale reasonably well. Once moved outdoors in spring, the plant soon recovers from the attack and its resident scale population, either from the changed environment or from predators, subsides. In the world of gardening, people are divided over how they feel about “standards.” Some gardeners love them, others will have nothing to do with them.

In the world of gardening, people are divided over how they feel about “standards.” Some gardeners love them, others will have nothing to do with them.

The strain Bt var. israelensis is toxic to larvae of black flies and mosquitoes. Another strain, Bt var. san diego, is toxic to Colorado potato beetle larvae.

The strain Bt var. israelensis is toxic to larvae of black flies and mosquitoes. Another strain, Bt var. san diego, is toxic to Colorado potato beetle larvae.

So, like mulberry, the plants can be pruned back some so they’re more manageable to be protected from bitter winter cold. An in-ground plant, then, could be protected from bitter winter cold by being swaddled upright or lowered to the ground, even trained to grow along the ground; a potted plant is more easily maneuvered into a garage, unheated basement, or other cool location for its winter rest.

So, like mulberry, the plants can be pruned back some so they’re more manageable to be protected from bitter winter cold. An in-ground plant, then, could be protected from bitter winter cold by being swaddled upright or lowered to the ground, even trained to grow along the ground; a potted plant is more easily maneuvered into a garage, unheated basement, or other cool location for its winter rest.