THE BEST HERB FOR A NORTHERN WINTER

Calamity Avoidance

A horticultural calamity averted. Again. Deb was snipping some leaves from our potted rosemary “tree” for salad dressing and said she noticed that the plant looked a little wilty. I was skeptical. Rosemary leaves are so narrow and stiff that they hardly broadcast their thirst. Still, quite a few rosemary plants have succumbed to winter drought here.

I checked the plant and, in fact, the leaves did look a bit wilty. The probe of my sort-of-accurate electronic moisture tester (which I nonetheless highly recommend) confirmed Deb’s diagnosis. The soil was very dry but, luckily, not to the point of killing the plant.

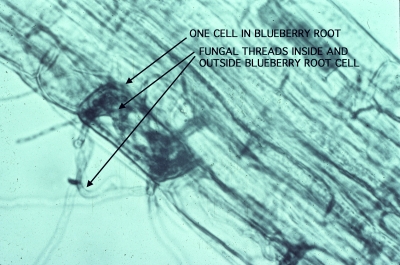

Allow me to digress . . . Soil scientists represent soil moisture levels with four descriptors. Right after a thorough watering, a soil is “saturated,” with all pores filled with water. Saturation is not desirable in the long term because roots need to “breathe” to do their work of drawing in nutrients and water, which is why plants exhibit the same symptoms from either dry or sodden soil.

Without additional water, gravity begins to pull water down and out of the larger pores of a saturated soil. Once gravity has pulled all the water it can from a soil, the soil is at “field capacity,” much to the pleasure of resident plants. At this point, large pores are filled with air yet some water, which is available for plants, is retained within smaller pores and clinging to soil particles.

Roots continue to slurp more and more water from the soil, but with increasing difficulty because water within even smaller pores and clinging even closer to soil particles is increasingly tightly held there by capillary attraction. Although the soil has moisture, it’s mostly inaccessible to plants. “Wilting point” has been reached.

Eventually, the only moisture left in the soil is that held very tightly in the very smallest pores and pressed tight against soil particles. That’s “permanent wilting point” from which, as the name implies, there’s no turning back. The plant will die.

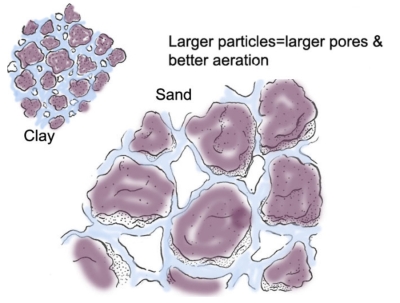

The actual amount of water in a soil at any of these stages depends on the range of particle sizes in the soil. Clay soils have tiny particles, with tiny spaces between them, so have more water at wilting and permanent wilting point than do sandy soils, with their large particles and large pores.

At or near field capacity, sands have more air and less water than clays.

Where were we? Oh, my rosemary plant. I’m figuring it was just teetering on the edge of wilting point. Needless to say, I watered both my rosemary “trees.”

(For a lot more about soil water and how to make the best of it, see my book The Ever Curious Gardener: Using a Little Natural Science for a Much Better Garden.)

Dry Air, Moist (Enough) Soil

You’d think — I once did — that rosemary, because in the wild it billows down dry hillsides overlooking the Mediterranean, would be resistant to drought. It does tolerate dry air. But those wild plants’ roots are in the ground where they can forage far and wide for moisture; not so in a pot.

Also, my rosemary plants are coddled with relatively consistent warmth in winter and a potting mix rich in nutrients. Couple this with low light conditions, even near a south-facing window, and you get very succulent growth. I don’t know what rosemary plants growing on a Grecian hillside are doing now, but my plants are growing like gangbusters. All that succulent growth transpires lots of water, and is very susceptible to drought.

Left half of this rosemary expired last summer

Once my plants go outdoors in summer, their leaves mature and toughen and growth is less succulent. They do still need sufficient moisture, so I have drip tubes on a timer quenching their thirst (and that of other plants). Except, that is, when the timer’s battery needs replacing and I don’t notice it. That was last summer. The plants were not at the permanent wilting point but a number of branches, which I pruned off, dried up, dead.

In Praise of Potted Rosemary

All this is not to frown upon growing rosemary where it can’t survive winters outdoors. On the contrary, I consider rosemary to be the finest herb for indoor growing. Flavorwise, it packs a powerful punch, unlike chives, for example, a plant that needs to be practically decimated if you really want to flavor something with it. Merely brushing against my rosemary plant releases an aromatic, piney cloud.

Rosemary is also a very attractive houseplant whether grown as a scraggly shrub reminiscent of the wild plants in their native haunts, trained as dense cones, or — as are my plants — as miniature trees. The leaves retain a healthy, verdant look, unlike those of basil, which look sickly and out of their element in dry, relatively dark and cool homes in winter.

Rosemary also rarely suffers from any insect or disease problem.

And finally, properly cared for, rosemary is perennial so can provide aroma, flavor, and beauty for many, many years.

But you and I do need to pay close attention to watering.

Rosemary, with its compatriots, bay and citrus, in summer

Remember the song lyrics: “House built on a weak foundation will not stand, no, no”? Well, the same goes for plants. (Plant with a weak root system will not be healthy, no, no.) Fertilization in the fall, rather than in winter, spring, or summer, promotes strong root systems in plants.

Remember the song lyrics: “House built on a weak foundation will not stand, no, no”? Well, the same goes for plants. (Plant with a weak root system will not be healthy, no, no.) Fertilization in the fall, rather than in winter, spring, or summer, promotes strong root systems in plants. The two major forms of soluble nitrogen that plants can “eat” are nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen. Nitrate nitrogen will wash right through the soil; ammonium nitrogen, because it has a positive charge, can be grabbed and held onto negatively charged soil particles. Therefore, if you’re going to purchase a chemical fertilizer to apply in the fall, always buy a type that is high in ammonium nitrogen. The forms of nitrogen in a fertilizer bag are spelled out right on its label.

The two major forms of soluble nitrogen that plants can “eat” are nitrate nitrogen and ammonium nitrogen. Nitrate nitrogen will wash right through the soil; ammonium nitrogen, because it has a positive charge, can be grabbed and held onto negatively charged soil particles. Therefore, if you’re going to purchase a chemical fertilizer to apply in the fall, always buy a type that is high in ammonium nitrogen. The forms of nitrogen in a fertilizer bag are spelled out right on its label.

I like to think of my compost pile as a pet (really, many pets, the population of which changes over time as the compost ripens) that needs, as do our ducks, dogs and cat, food, water, and air. Today I’ll feeding my pet — my compost pet — corn stalks, lettuce plants that have gone to seed, rotten tomatoes and peppers, and other garden refuse. Plenty of organic materials are available to feed compost piles this time of year.

I like to think of my compost pile as a pet (really, many pets, the population of which changes over time as the compost ripens) that needs, as do our ducks, dogs and cat, food, water, and air. Today I’ll feeding my pet — my compost pet — corn stalks, lettuce plants that have gone to seed, rotten tomatoes and peppers, and other garden refuse. Plenty of organic materials are available to feed compost piles this time of year. Joseph Jenkins, in his excellent (and fun-to-read) book, The Humanure Handbook, quotes research showing complete destruction of human pathogens in humanure composts that reach 145°F for one hour, 122°F for one day, or 109° F for one week. The same should be true for plant pathogens and pests. For decades, I’ve tossed everything and anything into my compost piles and never noticed any carry over of pest or disease problems.

Joseph Jenkins, in his excellent (and fun-to-read) book, The Humanure Handbook, quotes research showing complete destruction of human pathogens in humanure composts that reach 145°F for one hour, 122°F for one day, or 109° F for one week. The same should be true for plant pathogens and pests. For decades, I’ve tossed everything and anything into my compost piles and never noticed any carry over of pest or disease problems. This time of year, my compost piles dial the heat up to around 140°F, and hold that temperature for a couple of weeks, or more, before slowly cooling down.

This time of year, my compost piles dial the heat up to around 140°F, and hold that temperature for a couple of weeks, or more, before slowly cooling down. Also on the menu is some horse manure from a nearby stable, which I like mostly for the wood shavings that provide bedding for the horses. The manure itself furnishes nitrogen, which compost pets need for a balanced diet — 20 parts carbon to 1 part nitrogen but no need to be overly exacting because it all balances out in the finished compost. Lacking manure, soybean meal is another nitrogen-rich feed, as are grass clippings and kitchen waste.

Also on the menu is some horse manure from a nearby stable, which I like mostly for the wood shavings that provide bedding for the horses. The manure itself furnishes nitrogen, which compost pets need for a balanced diet — 20 parts carbon to 1 part nitrogen but no need to be overly exacting because it all balances out in the finished compost. Lacking manure, soybean meal is another nitrogen-rich feed, as are grass clippings and kitchen waste. Feeding a variety of compost foods provides a smorgasbord of macro- and micronutrients to the composting organisms and, hence, to my plants. Every few inches I also sprinkle on some soil, to help absorb nutrients and odors, and some ground limestone, to lower acidity of our naturally increasingly acidic soils, and to improve the texture of the finished compost.

Feeding a variety of compost foods provides a smorgasbord of macro- and micronutrients to the composting organisms and, hence, to my plants. Every few inches I also sprinkle on some soil, to help absorb nutrients and odors, and some ground limestone, to lower acidity of our naturally increasingly acidic soils, and to improve the texture of the finished compost.

It was too late to plant a late vegetable crop in the bed I just cleared of old corn stalks, so I blanketed that bed an inch deep in compost. The same goes for a bed in which grew an early planting of zucchini.

It was too late to plant a late vegetable crop in the bed I just cleared of old corn stalks, so I blanketed that bed an inch deep in compost. The same goes for a bed in which grew an early planting of zucchini.

All this prompted one reader, Peter, to comment with some specific questions that might also be of interest to some of you. I will now try to answer them.

All this prompted one reader, Peter, to comment with some specific questions that might also be of interest to some of you. I will now try to answer them.

The most obvious benefit of a cover crop is the protection it affords the soil from wind and rain, either of which can carry away the most fertile surface layer. Also protection from temperature extremes. Another benefit is that cover crops can suppress weeds. Less obvious is cover crop plants’ ability to grab onto and bring back up to the surface layers nutrients that rain might otherwise wash beyond roots into the groundwater.

The most obvious benefit of a cover crop is the protection it affords the soil from wind and rain, either of which can carry away the most fertile surface layer. Also protection from temperature extremes. Another benefit is that cover crops can suppress weeds. Less obvious is cover crop plants’ ability to grab onto and bring back up to the surface layers nutrients that rain might otherwise wash beyond roots into the groundwater.

In another bed, tomatoes are doing fine, but are not as vigorous as they should be as compared with another bed of tomatoes in that garden.

In another bed, tomatoes are doing fine, but are not as vigorous as they should be as compared with another bed of tomatoes in that garden. My notes indicate that both beds received their annual blanket of compost, just like all the other beds. Last fall, when the compost was applied, I also sowed cover crops in those beds. Rather than my usual oats cover crop, which winter-kills so integrates well with my no-till system, I sowed crimson clover along with the oats. Why crimson clover? Because it’s pretty when it blooms in spring.

My notes indicate that both beds received their annual blanket of compost, just like all the other beds. Last fall, when the compost was applied, I also sowed cover crops in those beds. Rather than my usual oats cover crop, which winter-kills so integrates well with my no-till system, I sowed crimson clover along with the oats. Why crimson clover? Because it’s pretty when it blooms in spring.