To Shred or Not To Shred, That is the Question

Organic Matters

My friend Margaret Roach (https://awaytogarden.com) is a top-notch gardener but not much of a tool maven. She recently said she considers me, and I quote, “the master of all tools and the king of compost” when she asked for my thoughts on compost shredders. (I blushed, but perhaps she was just softening me up for questioning. In fact, her tractor is better than mine.)

Of course I have thoughts about compost shredders.

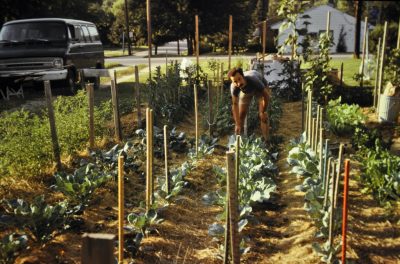

Climb with me into my time machine and let’s travel back to the early 1970s, to Madison, Wisconsin, where you’ll find me working in my first garden. Like any good organic gardener, early on I appreciated the many benefits of organic materials in the garden, an appreciation bolstered by my having recently began my studies as a graduate student in soil science.

I was hauling all the organic materials I could lay hands on into my 700 square foot vegetable garden. From near where I parked on the agriculture part of campus I could load up large plastic garbage cans with chicken or horse manure for my compost piles.

Also for my compost piles, and for mulch, was tall grass mowed by road crews along a major roadway, easily scooped up with my pitchfork and packed into those garbage pails. Nowadays, gathering such mowings would be difficult because the flail mowers now used chop everything up rather than lay down the long stalks of yesteryears’ sickle bar mowers. Gathering roadside mowings may also now be illegal. And, in retrospect, those mowings were (and still are) probably contaminated with lead and other heavy metals from nearby traffic.

Garden, Madison, 1970s

Anyway, I now have my own one acre field which I scythe and brush hog for mulch and feeding compost piles.

Bulk and Speed

But I digress . . . Margaret was asking about compost shredders.

One benefit of organic materials in gardening is their bulk; they are mostly carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, which, over time, ends up as carbon dioxide and water. That decomposition is a good thing because it represents the feeding of soil life and, as decomposition proceeds, plant nutrients are slowly released into the soil.

A downside of all that bulk is that it takes up a lot of space. The decomposition rate is influenced by the materials’ ratios of carbon to nitrogen, inhibitors such as lignin, and particle size. A given volume of smaller particles has greater surface area, accessible to being nibbled away by microbes, than does that same volume of larger particles. Like perhaps many beginning gardeners, I was in a rush to have better soil than the sticky clay I was dealing with.

Enter garden shredders. I headed down to the local Sears Roebuck and Company and purchased a new, gasoline-powered shredder. Back in the garden, I set it up and in little time was reducing large volumes of leaves to smaller volumes of shreds.

That activity probably lasted about 20 minutes before two thoughts entered my head. First, one reason I was gardening was because it was — or could be — good for the environment. I could grow vegetables more sustainably that most farmers of the day, and the vegetables would not have to be transported to me. Shredding seemed, then, a waste of energy. Second, the chugging of the engine didn’t seem to jive with a bucolic activity such as gardening. Fortunately, the shredder could be returned; I packed it up and got my money back. (Unless powered by solar, wind, or some other renewable energy source, and electric shredder also spews carbon dioxide et al. It just does so elsewhere.)

And anyway, there’s no particular need, generally, to speed up the composting process. If you need some finished compost immediately because of poor planning or a beginning garden, there are plenty of places where you can purchase good quality compost. Build a couple or more piles of your own, manage them well, and you’ll have “black gold” always ready in due time.

Solar Enters the Picture

I do still occasionally use a compost shredder — but it’s very quiet and it’s solar powered.

Also very inexpensive because it’s nothing more than a machete. If I’m piling very rough material such as corn or kale stalks, or very airy material such as old tomato or pepper plants, or large fruits such as overgrown zucchinis onto my compost pile, I’ll chop them with a machete as I add them. (It’s also therapeutic: If everyone spent some time chopping their compost ingredients, as needed, with a machete, the world would perhaps be a more peaceful place.)

The bottom line is that there’s no reason that you must shred any material for composting. That is, unless it’s absolutely necessary to speed things up or reduce their volume. Is it really necessary? Usually not.

I guess two plants per pole, with poles about a foot apart, is too crowded. Next year: one plant per pole.

I guess two plants per pole, with poles about a foot apart, is too crowded. Next year: one plant per pole.

I train my tomato plants to stakes and single stems, which allows me to set plants only 18 inches apart and harvest lots of fruit by utilizing the third dimension: up. At least weekly, I snap (if early morning, when shoots are turgid) or prune (later in the day, when shoots are flaccid) off all suckers and tie the main stems to their metal conduit supports.

I train my tomato plants to stakes and single stems, which allows me to set plants only 18 inches apart and harvest lots of fruit by utilizing the third dimension: up. At least weekly, I snap (if early morning, when shoots are turgid) or prune (later in the day, when shoots are flaccid) off all suckers and tie the main stems to their metal conduit supports. I lop wayward shoots either right back to their origin or, in hope of their forming “spurs” on which will hang future fruits, back to the whorl of leaves near the bases of the shoots.

I lop wayward shoots either right back to their origin or, in hope of their forming “spurs” on which will hang future fruits, back to the whorl of leaves near the bases of the shoots. Newly planted trees and shrubs are another story. This first year, while their roots are spreading out in the ground, is critical for them. I make a list of these plants each spring and then water them weekly by hand all summer long unless the skies do the job for me (as measured in a rain gauge because what seems like a heavy rainfall often has dropped surprisingly little water).

Newly planted trees and shrubs are another story. This first year, while their roots are spreading out in the ground, is critical for them. I make a list of these plants each spring and then water them weekly by hand all summer long unless the skies do the job for me (as measured in a rain gauge because what seems like a heavy rainfall often has dropped surprisingly little water). Not only vegetables get this treatment. Buy a packet of seeds of delphinium, pinks, or some other perennial, sow them now, overwinter them in a cool place with good light, or a cold (but not too cold) place with very little light, and the result is enough plants for a sweeping field of blue or pink next year. Sown in the spring, they won’t bloom until their second season even though they’ll need lots of space that whole first season.

Not only vegetables get this treatment. Buy a packet of seeds of delphinium, pinks, or some other perennial, sow them now, overwinter them in a cool place with good light, or a cold (but not too cold) place with very little light, and the result is enough plants for a sweeping field of blue or pink next year. Sown in the spring, they won’t bloom until their second season even though they’ll need lots of space that whole first season. Every time I look at a weed, I’m thinking how it’s either sending roots further afield underground or is flowering (or will flower) to scatter its seed. Much of gardening isn’t about the here and now, so I also weed now for less weeds next season. It’s worth it.

Every time I look at a weed, I’m thinking how it’s either sending roots further afield underground or is flowering (or will flower) to scatter its seed. Much of gardening isn’t about the here and now, so I also weed now for less weeds next season. It’s worth it.

The next bins weren’t bins but just carefully stacked layers of ingredients, mostly horse manure, hay, and garden and kitchen gleanings. And then there was my three-sided bin made of slabwood.

The next bins weren’t bins but just carefully stacked layers of ingredients, mostly horse manure, hay, and garden and kitchen gleanings. And then there was my three-sided bin made of slabwood.

Which brings me to my current bin which, now, after many years of use, I consider nearly perfect. Instead of hemlock boards, these bins are made from “composite lumber.” Manufactured mostly from recycled materials, such as scrap wood, sawdust, and old plastic bags, composite lumber is used for decking so should last a long, long time.

Which brings me to my current bin which, now, after many years of use, I consider nearly perfect. Instead of hemlock boards, these bins are made from “composite lumber.” Manufactured mostly from recycled materials, such as scrap wood, sawdust, and old plastic bags, composite lumber is used for decking so should last a long, long time. When finished, I ripped one board of the bin full length down its center to provide two bottom boards so that the bottom edges of all 4 sides of the bin would sit right against on the ground.

When finished, I ripped one board of the bin full length down its center to provide two bottom boards so that the bottom edges of all 4 sides of the bin would sit right against on the ground. Before setting up a bin, I lay 1/2” hardware cloth on the ground to help keep at bay rodents that might try to crawl in from below.

Before setting up a bin, I lay 1/2” hardware cloth on the ground to help keep at bay rodents that might try to crawl in from below. With the Lincoln-log style design, the bin need be only as high as the material within while the pile is being built, and then “unbuilt” gradually as I removed the finished compost.

With the Lincoln-log style design, the bin need be only as high as the material within while the pile is being built, and then “unbuilt” gradually as I removed the finished compost.

I wouldn’t find that many earthworms at work in my own grassy meadow. The last glacier, which receded about 12,000 years ago from the northern parts of the U.S., including here in the Hudson Valley, wiped out all the earthworms. Darwin’s meadow was spared because glaciation didn’t reach as far south as where Darwin’s home eventually stood.

I wouldn’t find that many earthworms at work in my own grassy meadow. The last glacier, which receded about 12,000 years ago from the northern parts of the U.S., including here in the Hudson Valley, wiped out all the earthworms. Darwin’s meadow was spared because glaciation didn’t reach as far south as where Darwin’s home eventually stood. These non-native earthworms are of concern because of the rapidity with which they gobble up organic matter. Their voracious appetites threaten the mountain laurels, rhododendrons, and blueberries that thrive in the organic matter — the leafy mulch — that blankets the forest floors in our nearby Catskill and Shawangunk Mountains.

These non-native earthworms are of concern because of the rapidity with which they gobble up organic matter. Their voracious appetites threaten the mountain laurels, rhododendrons, and blueberries that thrive in the organic matter — the leafy mulch — that blankets the forest floors in our nearby Catskill and Shawangunk Mountains. Through summer, pale pink milkweed blossoms dot the meadow. Come late summer, purple flowers of bee balm cap the sea of green grass like ocean whitecaps. And then, later and on into autumn, various species of yellow goldenrod bloom in succession. In the cool of the morning, dew and morning sunlight bring sparkle to the show.

Through summer, pale pink milkweed blossoms dot the meadow. Come late summer, purple flowers of bee balm cap the sea of green grass like ocean whitecaps. And then, later and on into autumn, various species of yellow goldenrod bloom in succession. In the cool of the morning, dew and morning sunlight bring sparkle to the show.

Grape sticks got plunged into the ground where they grew their own roots, shoots, and everything else. Apples aren’t so amenable to growing their own roots.

Grape sticks got plunged into the ground where they grew their own roots, shoots, and everything else. Apples aren’t so amenable to growing their own roots.

Roots of Rabbi Samuel fig, near the endwall, spread under the wall and outside the greenhouse, soaking up so much water that the figs split before ripening. Yet, a few fig fruits escape both afflictions and ripen to juicy sweetness.

Roots of Rabbi Samuel fig, near the endwall, spread under the wall and outside the greenhouse, soaking up so much water that the figs split before ripening. Yet, a few fig fruits escape both afflictions and ripen to juicy sweetness.