STUFFED

Breadcrumb Seeds?

Who’s getting stuffed for Thanksgiving this year, you or your turkey, or your tofurkey? A good stuffing (of the real or faux bird) is good enough to eat sans bird. And, for best quality, you can grow it yourself. Not by dropping seeds of a “stuffing plant” in the soil, but by planting all the ingredients you need.

The bread and butter of any stuffing is some starchy food, often bread and butter itself, the bread usually as crumbs. There’s no breadcrumb plant, so forget about growing breadcrumbs. Not that you couldn’t buy some wheat berries, plant them next spring, harvest the grain when the plants dry down, thresh and winnow out the berries, grind them into flour, make the flour into bread, then let the bread go stale and pound it into bread crumbs. Whew! Most of us are not going to do this.

“The Bread Tree”

As an alternative to bread crumbs, might I suggest chestnuts (Castanea spp.)?  They’re often billed as the “bread tree” because in contrast to other nuts, which are high in fats and protein, chestnuts are high in starch. Obviously, you’re not going to be eating home-grown chestnut stuffing this year, or next, or the next; it takes awhile for a chestnut tree to start bearing. Not that long though. I’ve had plants grown from seed begin to bear within six years, and a grafted tree from a nursery should bear even sooner than that.

They’re often billed as the “bread tree” because in contrast to other nuts, which are high in fats and protein, chestnuts are high in starch. Obviously, you’re not going to be eating home-grown chestnut stuffing this year, or next, or the next; it takes awhile for a chestnut tree to start bearing. Not that long though. I’ve had plants grown from seed begin to bear within six years, and a grafted tree from a nursery should bear even sooner than that.

(Although their nuts look similar, chestnuts should not be confused with horse chestnuts, Hippocastanum spp.. The latter are toxic. Horse chestnuts have compound leaves, very showy flowers, and their nuts are encased in a spiky capsule. Edible chestnuts have simple leaves, nonshowy flowers, and the nuts are encased in a cupule riddled with very sharp spines.)

The North American, native and majestic American chestnut (C. dentata) has been decimated by chestnut blight but there are, fortunately other species that resist the blight. A good choice for nut production would be species or hybrids of Chinese chestnut (C. mollisima). Two different varieties are needed for cross-pollination.

The only caution in planting chestnut trees is to avoid planting them near where people frequently walk. Each fall the ground beneath the trees is littered with the opened, spiny cupules.

More Crumby Alternatives

While you are waiting to harvest chestnuts, make stuffing based on one of the more quickly grown starchy vegetables. Potatoes, for instance. The best potatoes for making stuffing will be those that are dry and mealy, russet varieties such as Goldrush, Burbank, and Idaho.

“Dry and mealy” is also the mantra to use when choosing a winter squash variety to grow as a base for stuffing. The phrase “squash stuffing” has a nice ring to it, doesn’t it? My recommendation for a dry, mealy squash is a buttercup type called Chestnut or Sweet Mama.

If you really want a truly authentic starchy base for stuffing, the plant to grow is nu nu, a golfball-sized, starchy tuber also called makoosit or groundnut (Apios americana).  Native Americans harvested and ate nu nu, and this was one of the foods crucial in helping the Pilgrims survive their first winters in Massachusetts.

Native Americans harvested and ate nu nu, and this was one of the foods crucial in helping the Pilgrims survive their first winters in Massachusetts.

Be careful planting nu nu because it can spread like a weed to give you more stuff for stuffing than you would ever need. I planted it in a perennial flower bed decades ago. That was the wrong place for it, and I’ve spent decades trying to weed it out, unsuccessfully.

On the plus side, the plants do sport decorative and sweetly fragrant, lilac colored flowers, so it is worth growing where it can be regimented. Nu nu tubers grow attached a few inches apart along underground stems.

Seasonal Seasonings

Stuffing isn’t only about the bread-y ingredient. It also needs some seasoning. Parsley, sage, rosemary, and thyme, summer savory, sweet marjoram — they’re all very easy to grow. Sage and thyme are perennials, each also available in designer flavors. Pineapple sage, caraway thyme, and lemon thyme, for instance.

Rosemary is also a perennial, cold hardy to zone 7, possibly even zone 6. It’s is not hardy here but I grow it as a “standard” (trained as a small tree) in a pot that summers outdoors and lives indoors at a sunny kitchen window in winter to provide pretty greenery, piney fragrance, and savory snippings.

Some vegetables from the garden round out and make more interesting a stuffing. Onion, celery, and carrots are mainstays, but vegetables such as parsnips and garlic can make special — and powerful — flavor contributions.

Have a happy and healthy Thanksgiving!

But I’m writing about color, and Persian ironwood has it, the leaves emerging purplish in spring, turning a lustrous green in summer, then morphing into variable shades of yellow, orange and red in autumn.

But I’m writing about color, and Persian ironwood has it, the leaves emerging purplish in spring, turning a lustrous green in summer, then morphing into variable shades of yellow, orange and red in autumn.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is another fruit plant here, this one with many tropical aspirations. Tropical aspirations? It’s the northernmost member of the mostly tropical Custard Apple family (Annonaceae); its fruit has taste and texture reminiscent of banana; the fruits hang in clusters like bananas; and its long, drooping leaves would be visually at home in tropical climes. Come fall, the plants shed those tropical aspirations as the leaves turn clear yellow, especially nice when backlit by sunlight.

Pawpaw (Asimina triloba) is another fruit plant here, this one with many tropical aspirations. Tropical aspirations? It’s the northernmost member of the mostly tropical Custard Apple family (Annonaceae); its fruit has taste and texture reminiscent of banana; the fruits hang in clusters like bananas; and its long, drooping leaves would be visually at home in tropical climes. Come fall, the plants shed those tropical aspirations as the leaves turn clear yellow, especially nice when backlit by sunlight.

I grow only Sweet Mama and Waltham winter squashes. The first variety is botanically Cucumbita maxima and the second is C. moschata; the two species do not cross-pollinate.

I grow only Sweet Mama and Waltham winter squashes. The first variety is botanically Cucumbita maxima and the second is C. moschata; the two species do not cross-pollinate. Distance between varieties can prevent cross-pollination. So can fine mesh bags. I plan to use small organza bags normally sold for wedding favors.

Distance between varieties can prevent cross-pollination. So can fine mesh bags. I plan to use small organza bags normally sold for wedding favors.

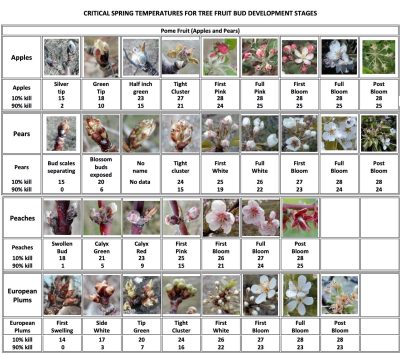

Great. Even better, temperature (as well as humidity) is recorded, and can be displayed graphically or downloaded to my computer. So I didn’t have to be awake to find out the mercury hit 32.5°F at 12:16 AM on the night of April 17th and stayed there until it began rising around 7 AM.

Great. Even better, temperature (as well as humidity) is recorded, and can be displayed graphically or downloaded to my computer. So I didn’t have to be awake to find out the mercury hit 32.5°F at 12:16 AM on the night of April 17th and stayed there until it began rising around 7 AM.

I also planted a white oak (Quercus alba), whose sturdy limbs, I figured, would slowly spread wide with grandeur in about 150 years, after the maples and birches were perhaps long gone. Unfortunately, the white oak died, probably due to winter cold; its provenance was a warmer winter climate. My mistake.

I also planted a white oak (Quercus alba), whose sturdy limbs, I figured, would slowly spread wide with grandeur in about 150 years, after the maples and birches were perhaps long gone. Unfortunately, the white oak died, probably due to winter cold; its provenance was a warmer winter climate. My mistake.