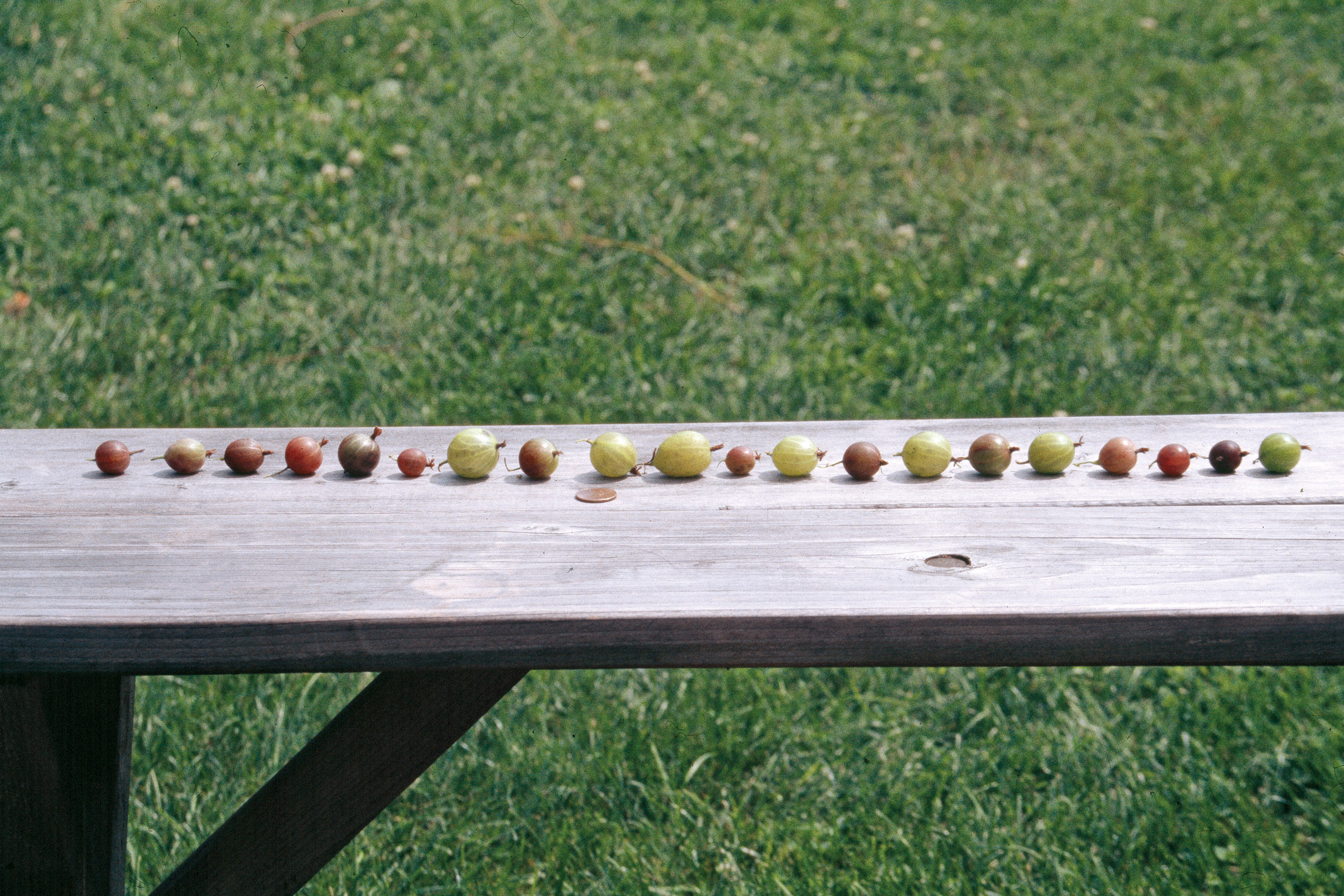

TOO MANY GOOSEBERRIES

/62 Comments/in Fruit/by Lee ReichAm I a Hoarder?

I once had what may have been the largest collection of gooseberries in this country east of the Rocky Mountains — four dozen or so. Many more existed and exist in collections across “the pond,” especially in Great Britain. That was due, in large part, to the gooseberry contests held annually since the 18th century in the clubrooms of inns, especially in Lancashire, Cheshire and the Midlands. Flavor be damned: rewards went for the largest berries. The gaiety of singing and refreshments at these shows was offset by the solemn weighing of fruits.

Those winning berries were the handiwork of amateur breeders and some rather esoteric horticulture. Suckling a promising berry, for example, whereby a saucer of water was perched beneath an individual berry throughout its growth, just high enough to wet only its calyx (far end).

Those winning berries were the handiwork of amateur breeders and some rather esoteric horticulture. Suckling a promising berry, for example, whereby a saucer of water was perched beneath an individual berry throughout its growth, just high enough to wet only its calyx (far end).

A MATTER OF TASTE

/7 Comments/in Vegetables/by Lee ReichMost Important, to Me at Least

Hints of summer already are here, not outside, but in the seed catalogues in my mailbox, on seed racks in stores, and from emails from seed companies. Look how many different varieties of each vegetable are offered! Thumbing through one (paper) catalogue, for example, I see twenty-eight varieties of tomato, seventeen varieties of peas, and eleven varieties of radishes. Anyone who has gardened for at least a few years has their most and least favorite varieties of vegetables. Here’s a sampling of mine.

Right from the start, I admit that most important to me in choosing a vegetable variety is flavor. I’ll grow a low-yielding variety, even one that’s not particularly resistant to insects or diseases, if it is particularly delectable. Within reason, of course.

Let’s start with one of the most widely-grown backyard vegetables, tomatoes.

REVEALED

/0 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichOnly for Gray-Haired Ladies?

I’m coming out. Today. Let me explain.

Decades ago, when just starting getting my hands in the dirt, I — perhaps other people, perhaps it was even true — thought it was only gray-haired ladies who grew African violets. As it turns out, a number of years after I had started gardening, I was offered an African violet plant (by a gray-haired lady). Back then, before I had accumulated too many plants, I was less discriminating than I am these days. I accepted.

I figured I could provide the special conditions African violets demand, according to what I read in numerous publications. “Proper watering and soil moisture is critical to your success,” I was told by one publication. I could provide the needed consistently moist soil with a potting mix especially rich in peat, compost, or some other organic material. I could monitor the plants thirst by lifting the pot to feel its weight or by periodic probing its soil with my electronic moisture meter.  I could of course be careful to avoid leaf spotting by not spilling any water, especially cold water, on the leaves. Watering from below would do the trick, with periodic leaching from above to prevent buildup of salts. They also like high humidity.

I could of course be careful to avoid leaf spotting by not spilling any water, especially cold water, on the leaves. Watering from below would do the trick, with periodic leaching from above to prevent buildup of salts. They also like high humidity.

Other requirements of African violets that were and are stated are temperatures 70-90 degrees (F) by day and 65-70 degrees at night. I was also admonished to keep an eye out for pests, including aphids, cyclamen mites, and mealybugs, and symptoms of disease. Root rot, for example.

Oh, and regular feeding should be administered except when resting (to the plants, not me).