PARING DOWN PEARS

/10 Comments/in Fruit/by Lee ReichSo Much From Which to Choose

Pear espalier in Mt. Vernon, WA

Of all the common tree fruits, pears are the easiest to grow — and not just here in New York’s Hudson Valley. My site is admittedly poor for tree fruits, the flat lowland acting like a reservoir into which cold, damp air flows, leading to increased threats from diseases and late frosts. Proximity to acres and acres of forest provides haven for insect pests.

But I’m not complaining; the air might be bad for apples, peaches, cherries, plums, and apricots, but underfoot is rich, well-drained, rock-free river bottom soil that grows very nice vegetables, berries, and many uncommon fruits such as persimmons, cornelian cherries, and kiwifruits. And pears.

Of the more than 3,000 varieties of pears, only a handful are well-known. I figured, as with apples, there must be many varieties better or as good-tasting as the few usually offered in markets. Back in 2004, twenty dwarf apple trees that I’d planted were nearing the end of their productive life. So I dug them out, which left me with space for a number of dwarf or semi-dwarf pear trees. But what varieties to plant? I sought suggestions from other fruit growers, from nursery websites and catalogues (especially Raintree Nursery and Cummins Nursery), from the USDA Pear Germplasm Repository, and books such as the 100-year-old tome The Pears of New York, finally settling on sixteen varieties (listed at the end of this blog post to avoid boring you if you don’t want such detail).

AND THOREAU ADVISED…

/7 Comments/in Soil/by Lee ReichBiochar vs. Wood Chips

People are funny. Take, for instance, a fellow gardener who, a couple of months ago, shared with me her excitement about a biochar workshop she had attended. “I can’t wait to get back into my garden and start making and using biochar,” she said.

Biochar, one of gardening’s relatively new wunderkind, is what remains after you burn wood with insufficient air. It’s charcoal. Stirred into the soil, its myriad nooks and crannies provide an expansive adsorptive surface for microbes and chemicals, natural and otherwise. Biochar, being black, darkens the soil, and dark soil is generally associated with fertility, although that’s not always the case. Because biochar is mostly elementary carbon, it resists microbial decomposition, so it’s carbon is less apt to end up in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

In contrast, when raw wood — wood chips or sawdust, as examples — are added to soil, it feeds microbes and then plants as it decomposes, eventually turning to organic matter, sometimes called humus. Humus is a witch’s brew of compounds with beneficial effects on soil’s nutritional, biological, and physical properties. So is cooking up a batch of biochar and digging it into your soil better for the soil and really worth the effort?

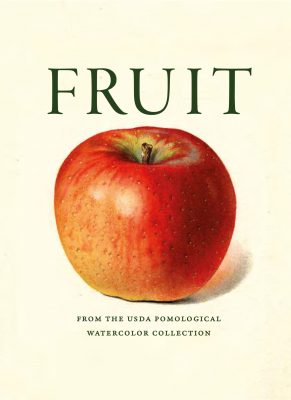

ART, HISTORY, AND QUAINT NAMES

/4 Comments/in Books, Fruit/by Lee ReichThe U.S. Dept. of Agriculture Supporting Artists?!

I’ve been thumbing through my latest book, Fruit: From the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection. Most of the book is illustrations of many kinds and varieties of fruits painted by 20 artists over the years from 1892 to 1946. Most obvious is the beauty of the paintings. Less obvious is what they tell of fruit growing and marketing in this country.

For instance, why were the watercolors commissioned — by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, no less? To answer that question let’s first backtrack to before the middle of the 19th century. Up until then, fruit trees were planted mostly for cider, brandy, or to feed pigs. Fermented beverages were a more healthful drink than water at the time. (Just imagine all the tipsy kids wandering around!)