BLEEDING PLANTS, WHAT ABOUT RABBITS?

/1 Comment/in Gardening, Pruning/by Lee Reich

Bleeding Is Okay

Everyone wants to prune this time of year. And rightly so. It’s a good time to prune most trees, shrubs, and vines, as it was a couple of months ago and, looking forward, will be until about when these plants come into bloom. Or, finished blooming, in the case of those plants whose pruning gets delayed until after we all get to enjoy their early blossoms.

A reader wrote me about her Japanese maple, which needed to have one of its multi-trunks cut off. Should she do it now or in autumn? If lopped back now, would the tree bleed to death? Would the gaping wound get infected, possibly leading to the demise of the whole tree?

Japanese maple in fall

Bleeding sap generally does more harm to gardeners’ psyches than to plants’ physiologies. My grape and hardy kiwi vines bleed when I prune them this time of year, with no harm done. So why worry about harm to a maple?

(The bleeding of grapevines that climb the arbor over my patio does have one downside. It’s very pleasant to sit outdoors on that patio on warm, spring days; it’s very unpleasant to sit where sap drips on my head.)

Root pressure of water being forced up the vines is what makes grape and kiwi vines bleed. Once leaves unfold, they take up that pressure and bleeding ceases.

Root pressure is not what forces sap (which sounds more benign than “bleeding”) out of wounds of maple trees. With maples, cooling temperatures cause gas bubbles in xylem cells (the inner ring of trees’ cells in which liquid is conducted upwards from the roots) to shrink and to dissolve. Something’s got to fill that newfound space, so more liquid is sucked up from the roots and into the cells. As temperatures drop further, ice forms and gases are locked within the developing ice. Come morning, pressure builds in the cells as rising temperatures melt the ice and release the gases. The expanding liquid is forced out any holes in the bark, whether from a maple sap spile or from a pruning wound.

Although maples bleed for a different reason than do most other plants, the bleeding itself causes no harm to the plants. The reason small maple trees, with trunks narrower than 6 inches in diameter, should not be tapped is because the wound left by the tap hole extends within the trunk beyond the hole; sap will never again travel past the wounded area. A tap hole is large in relation to the size of a small tree’s trunk, so significantly restricts liquid flow.

Of course, there’s no need to conduct sap up a trunk that’s been lopped off. So, Barbara, go ahead and prune, now, when the gaping wound can soon begin to heal. Autumn, which leaves a gaping wound exposed to the elements and pests until spring, would be a very bad time to prune.

A Wabbit!!!!

I looked out the window awhile ago to see a rabbit crouched against a backdrop of pure, white snow. How cute. NOT! It’s the same old story. Farmer McGregor and Peter Rabbit, and now farmdener me and some other rabbit.

A few days previously I had noticed that some bark had been nibbled off the pencil-thick “trunks” of some young, grafted trees — the handiwork of those awful furballs. That nibbling probably won’t kill the small plants but will set them back a year, or more, if the nibbling kills the scion down to the graft.

As for the rabbit and its probable kin, I’m setting traps. Unfortunately, my Peter Rabbit seems to enjoy my plants more than anything I put in the trap.

Rabbit, At Bay

I’ve kept my Peter Rabbit at bay from all my older trees this winter with diligence and hardware cloth and or commercially available plastic spiral tree guards. The protection goes 2 feet above ground, or higher, not that a rabbit could reach that high — except when there’s snow to give it “a leg up.” The light-colored spirals also protect the thin barks of young trees from sunscald, which results when sunny, cold winter days warm the bark, whose temperature then plummets as the sun drops below the western horizon.

I remove all the spirals in spring so insects can’t find shelter from birds beneath the spirals.

Monthly, throughout winter and into early spring, I also sprayed plants with Bobbex, a mix of “putrescent whole egg solids,” garlic, and cloves that is repellant to rabbits, as well as deer (and me).

And finally, there’s Sammy, my trusty dog who would chase away any rabbits if he happened to be awake, happened to be on the right side of the house, and happened to see them.

MOVING ALONG, INSIDE AND OUT

/10 Comments/in Flowers, Fruit, Gardening, Planning/by Lee Reich

Figs Awakening

Even in the cool temperature (45 degrees Fahrenheit) and darkness of my basement, the potted figs can feel spring inching onward. Buds at the tips of their stems have turned green and are just waiting for some warmth to burst open. Or, if the plants just sit where they are long enough, the buds will unfurl into leaves and shoots. Which would not be a good thing.

My goal is to keep the plants asleep long enough so that they can be moved outside when they will no longer be threatened by cold temperatures. How much of a threat temperatures pose depends on how much asleep the plants are. Fully dormant, a fig tree tolerates temperatures down into the low 20’s. Even now, as they are just barely awakening, they can probably laugh off temperatures into the mid-20s.

If the buds expand into shoots and leaves, they’ll be burned by any temperature below freezing. And especially so if those new shoots and leaves get started indoors, where warm temperatures and relatively low light makes for overly succulent growth. Bright sunlight, even without freezing temperatures, can then cause damage.

Fig plants that start growing in earnest indoors get presented with two options. The first is to get them to the sunniest window in the coolest room so that growth is more robust, then move them outdoors after any threat of frost has passed — about the same time as tomato transplants get planted out. (Around here, that’s about the third week in May.)

The second option is to move them outdoors as soon as temperatures won’t again fall below the mid-20s. Temperatures below 32 will burn the succulent, new shoots and leaves, but plants will push forth new growth well-adapted to the great outdoors. If an Arctic blast is predicted, with lower that usual temperatures — that is, below about 25 degrees Fahrenheit — the plants need to be moved temporarily to the garage, mudroom, or other convenient shelter.

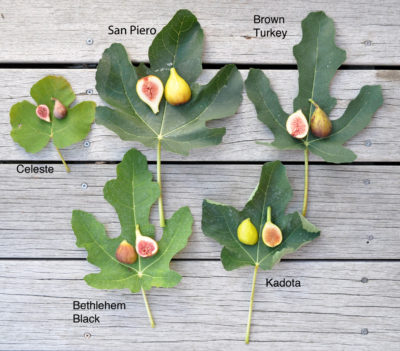

Different Strokes For Different . . . Figs

A fig’s treatment depends on the variety. Genoa, Excel, and Ronde de Bordeaux are three new varieties that I hope to taste this summer. They’ll get first-class coddling: Moved outside soon, then put into temporary shelter at the slightest hint that damaging temperatures could arrive. I might just put the others outside, and leave them there.

The Kadota fig gets planted, in its pot, right in the ground. Its roots will grow out through all the holes I drilled in the side and bottom of the pot so the plant becomes self-supporting, waterwise, until fall. I’ll plant it out soon, even though once it’s planted, it’s staying put all season long. (I have a backup plant.)

Too Weird To Eat

Moving forward into spring — on into late spring — brings dogwoods into bloom. Blossoms of our native flowering dogwood (Cornus florida) will soon be followed by those of kousa dogwood (C. kousa), and also called Japanese or Korean dogwood), native to east Asia.

The flowers of both species are very small and pretty much green. “Not so!,” you say, thinking back to last spring’s show of large white or pink petals. Those large white or pink things are, in fact, not petals, but bracts, which are modified leaves that, admittedly, serve pretty much the same function as petals, that is, to look pretty, attract pollinators, etc.

Over the years, the spring show from flowering dogwoods has become sparse because of powdery mildew and other diseases. Which is why kousa dogwood, which is disease resistant, has been increasingly planted.

Flowering dogwood can have either pink or white flowers — whoops, I mean bracts. Until recently, kousa dogwood came only in white. But now, breeders at Rutgers University, after decades of work, have introduced Scarlet Fire kousa dogwood, a cold hardy (Zone 5 to 8), disease resistant variety bearing pink bracts.

The flowers of kousa dogwood, whether pink or white bracted, are followed by edible fruits. The round fruits are the size of a quarter, dark pink, and very weird-looking. To me, they look like water (naval) mines, not a very friendly association for a fruit. Their appearance has also been described as that of a sea urchin shell, also not very gustatory. Inside, the flesh is sweetish and mealy, something like a cross between mango and pumpkin — not my two favorite flavors, but even if they were, those dark pink water mines are too off-putting in appearance for me to more than sample them (just so I could report on their flavor).

Still, kousa fruits add to the show from the flowering bracts and the healthy foliage.

HINTS OF SPRING, REMEMBRANCE OF SUMMER

/12 Comments/in Flowers, Gardening, Planning, Vegetables/by Lee Reich

Greenery, For Humans And Ducks

Spring has come early, as usual, in my greenhouse. Growth is shifting into high gear as brighter sunlight fuels more photosynthesis and warms the greenhouse more and for a longer time each day. Giant mustard plants, which provided greens all winter, are no longer tasty now that they have shifted their energy to stalks topped with yellow flowers. No matter. I’m digging the plants out and sowing lettuce seeds.

Paths in the greenhouse are carpeted in green — mostly from weeds, mostly chickweed, which is also soaking up the sun’s goodness. No matter. I’m also digging these plants out before they go to seed and threaten takeover of the greenhouse.

To take over the greenhouse, the chickweed would have to do battle with claytonia, which already has self-sown to bogart much of the greenhouse floor. Fortunately, the claytonia is good fresh in salads.

Chickweed is also good — to some people — for eating. But not for me. My ducks, however, love the stuff. So it’s a win-win situation. I weed the greenhouse paths, gather together a pile of chickweed, then throw it to the ducks as I walk past them on my way back to the house. They rush over to reach it soon after it hits the ground, gobbling it up at a frantic (for a human) pace. Good thing they don’t have to chew.

The ducks also enjoy the flowering mustard plants which, along with the chickweed, transmute into delicious duck eggs.

Bottled Summer Goodness

A couple of weeks ago I finished off the last of the elderberry fruit syrup I made this past fall. No fruit could be easier to grow than elderberry. In just a couple of years, the bushes have grown to enormous size, their clusters of creamy white flowers bowing to the ground at the ends of stems late each spring. Later in summer, those flower clusters morph into blue-black fruits, which, admittedly, aren’t very flavorful plain (and shouldn’t be eaten raw).

The only care I’m planning for my plants is to prune them every year or so. Pruning will entail cutting some of the older stems to the ground to make way for younger, more fruitful stems, as well as shortening any branches that arch down so much that their fruit would rest on the ground.

In summer, I stripped the ripe fruits from their clusters into a half-bushel basket, and, postponing what to do with them, froze them. Come fall, I cooked them in a little water, added some maple syrup, crushed them with a potato masher, and then jarred them up.

Why all this trouble for a fruit that’s not very flavorful? Because the berries are so healthful! Studies have shown them, or their extracts, to be “supportive agents against the common cold and influenza.” Other benefits have also been ascribed to use of elderberry, but common cold and influenza are enough for me.

Now that I’m out of elderberry syrup, I already feel a slight cold coming on.

Timing Is Important

Back to the greenhouse . . . and sowing seeds of the cabbage family (Brassicaceae), also called crucifers. Which gets me thinking back to last fall when a friend was bemoaning the lack of fat sprouts and the puny growth of his brussels sprouts plants. I asked when he sowed the seeds. “Back in early August,” I think he said. At any rate, back in summer.

It’s no wonder he wasn’t going to be harvesting brussels sprouts. The plants need a long season to mature, from 90 to 120 days, depending on the variety. For best yields, this means sowing seeds now, growing them as transplants for about 6 weeks, and then planting them out for harvest that will begin in late summer. At the very least, the seeds could be planted directly in the ground in a few weeks.

I’m sowing other crucifers now, not because they need such an inordinately long growing season, but so that they can be harvested in late spring and early summer. First harvests will be of miniature bok choys, and then cabbages and, if I grew them (I don’t), broccoli and cauliflower. Kale is the most versatile member of the family — and the one I grow in greatest quantity — amenable to sowing anytime from now until later in summer for harvest in late spring, through summer, and on into fall and winter.

Mustard, turnips, and arugula are also crucifers, the whole family most easily identified by their four-petaled blossoms in the shape of a cross, the root of the word crucifer.