PERENNIAL VEGGIES AND A DEAD AVOCADO

/11 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Vegetables/by Lee Reich

King Henry Was, And Is, Good

The good king has gone to seed. Good King Henry, that is. A plant. But no matter about that going to seed. The leaves still taste good, steamed or boiled just like spinach.

The taste similarity with spinach isn’t surprising because both plants are in the same botanical family, the Chenopodiaceae, or, more recently, the Amaranthaceae. Spinach and Good King Henry didn’t change families; their family was just taken in by, and made into a subfamily of, the Amaranthaceae.

Whatever its name — and it’s also paraded under such common names as poor man’s asparagus and Lincolnshire spinach — Good King Henry is a vegetable that’s been eaten for hundreds of years, except hardly ever nowadays. While spinach, beet, and some of its other kin have been improved by breeding and selection over the years, Good King Henry was neglected.

But the Good King, besides having good flavor, has a few things going for it lacking in spinach. It’s a perennial plant, it’s edible all season long, and it has no pests problems worth mentioning. This Mediterranean native made its way to my garden over 20 years ago, from seed I purchased and sowed. I haven’t had to replant it since then.

Which brings me to one possible downside of Good King Henry: It keeps trying to spread beyond the far corner of the garden where I originally planted it. Every spring I yank out errant plants, and eat them.

One of my favorite things about Good King Henry is its species name, bonus-henricus, making its whole botanical name Chenopodium bonus-henricus.

Another Perennial Oldie

Another perennial vegetable that I’ve enjoyed this spring is seakale (Crambe maritima), a relative of cabbage, broccoli, and kale. This also is an old-timey vegetable, one whose popularity peaked in the 18th century; Thomas Jefferson was a fan.

The origin of the name may trace to the leaves (kale-like) being pickled to bring aboard ships (the “sea” part of the name) to prevent scurvy.

Seakale, though perennial, does not spread. I started my plants from seed a few years ago, which is tricky only because the seeds have a low germination percentage. I’ve seen a few seedlings pop up a foot or so from the mother plant, which I welcome as an easy way to multiply my holdings.

Seakale tastes very good either cooked or raw, something like a mild cabbage with a refreshing touch of bitterness. Either way, blanching is needed to make it tasty, and that entails nothing more than covering it for a couple weeks or so, more or less depending on the weather (more warmth, less time), to keep out light and make the shoots more mild and tender. I invert a clay flowerpot over the whole plant, with a stone or saucer over the drainage hole to keep light from wending its way in. Like asparagus, new leaves eventually need to be set free to bask in the sun to fuel the roots for the next year’s early shoots.

One more plus for seakale is that the plant is a beauty, so much so that it’s sometimes planted as an ornamental. The wavy, pale bluish green leaves have a silvery pallor reminiscent of the British seascape to which they are native. Later in the season, a seafoam of white blossoms rises from the whorl of leaves.

I Give Up

Now for an about face, from European plants enjoying cool weather and sometimes dry conditions, to a tropical American plant. Awhile back I wrote about my efforts to grow avocados here in New York’s Hudson Valley. Not on a large scale; just one or two plants from which I could harvest a few fruits of some special variety.

I grew two plants from seeds I saved from locally purchased avocado fruits, and grafted onto those seedlings the stems of two varieties a gardening buddy sent up from Florida. Ungrafted, the seedling plants would bear fruit of unknown quality, if they bore at all. Grafted plants would give me improved, named varieties that would bear quickly.

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

I failed. Only one graft took, yet two varieties are needed for fruiting. As expected, the grafted stem on the successfully grafted plant flowered within a year of grafting. For days I tried to get the pollen from the male to pollinate the female parts of the flower — to no avail. And then, for some reason, the grafted stem started to darken and turn black, and died back.

I give up on trying to grow an indoor-outdoor avocado plant — for fruit — in a pot.

PERMACULTURAL GLITCHES

/6 Comments/in Design, Fruit, Gardening, Planning, Pruning/by Lee ReichImperfect Lawn

I’m no devotee of the perfect lawn, but I did recently suggest, for the bare palette of ground on which W wanted to plan for a variety of fruits, a patch of lawn. W protested that she hated mowing and wanted a “permaculture planting” that would take little care.

Visitors to my garden have occasionally complimented me on my lawn. The only care I give it is mowing with a mulching mower that lets clippings rain back down. By not cutting the lawn I avoid “mining” the soil for nutrients by repeated harvest of clippings. The clippings also enrich the ground with humus.

Pawpaw tree in my cousin’s lawn

Still, I’d rather grow trees, shrubs, vines, especially fruiting ones, and vegetables and flowers, than lawngrass. But I have plenty of ground devoted to these plants. And the easiest way to care for a plot of ground, short of sealing it in asphalt or just letting weeds grow (some of which would undoubtedly be edible or attractive) is by mowing. Visually, lawngrass also provide a calm backdrop for the scene out my back and front door. Plus, it’s nice to walk and play on.

A lawn need not be the environmental disaster inadvertently promoted by purveyors of fertilizers, and pesticides. As stated above, by letting clippings fall where they may, ground is not drained of its fertility, so fertilizer may not be needed. Especially if you let a little clover invade the lawn to add nitrogen, the most evanescent of plant nutrients.

That nitrogen highlights another approach to an easier lawn: Not striving for the uniform look of artificial turf. My lawn has its share of dandelions and clover and, later in the season, crabgrass, especially if the weather turns dry. I tolerate all this, with a refocussing of my aesthetic lens to celebrate a certain amount of diversity in the lawn.

Lawn care is even more environmentally sound these days with cordless electric lawnmowers not spewing noise, carbon dioxide, and other byproducts of gasoline consumption into the air. Periodic scything is a very pleasant way to get by with less mowing and sheep may be a way to get by with no mowing (but you do have to fence and do whatever else is necessary to care for the sheep).

Eco-mowers: Fiskars push, Stihl battery, and Scythe Supply Co. mowers

Fruits To (And Not To) Grow

Now for W’s permaculture fruit trees, shrubs, and vines — with some lawn, of course. (I think I convinced her.) For starters, I suggested steering clear of apples, peaches, plums, cherries, nectarines, and apricots. All are relatively high maintenance and, even with all that maintenance, still are iffy crops in this part of the world because of our extreme and variable climate and the plants’ susceptibilities to insects and diseases.

Nanking cherry hedge

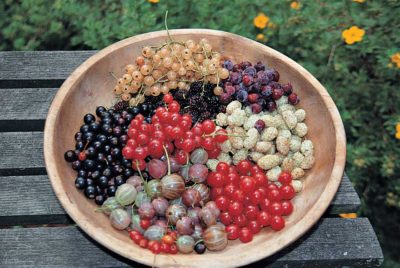

So what’s there left to grow??!! Berries, for one. Most berries don’t stand up well to commercial handling so are picked underripe even though they don’t ripen at all once harvested — all the more reason to grow berries in the backyard where the best tasting varieties can be planted and the harvest need not be shipped much further than arms’ length.

Redcurrant espalier

Raspberries, blackberries, blueberries, and strawberries are all easy to grow without much care beyond pruning, which is very important for keeping the plants disease free and convenient to harvest.

And no need to restrict the berry bowl to these most common berries. Also easy to grow are seaberries, elderberries, lingonberries, mulberries, and hardy kiwifruit (which are, botanically, berries). An added plus for these latter berries, as well as the aforementioned blueberries, is that the plants are also ornamental.

There is one common tree fruit that’s easy to grow: pears. And even easier than European pears, such as Bartlett, Anjou, and Bosc, are Asian pears, such as Chojuro, Yoinashi, Hosui, and scores of other varieties. Asian pears also bear more quickly and prolifically, and are a little more decorative than the also decorative European pears.

Asian pear, comfrey, and lawn

Avoiding Nightmares

The main problem that I’ve seen with many permaculture plantings is that they look great on paper as well as when first planted. Mouths water at the prospects of all those ornamental, fruiting plants cozied together, fruit on creeping plants beneath trees whose branches strain downward with their weight of fruit. And perhaps a nearby grape or kiwifruit plant insinuating its berried vines in among the trees’ branches.

I’ve seen such plans and such plantings. What a nightmare of management they are or will be, mostly because of the need for relentless, extensive, judicious pruning to keep some plants from overtaking the landscape and starving others for nutrients or light. The result is less fruit of lower quality and difficulty in finding the fruit and getting to it.

A little lawn is good to give the fruiting plants some elbow room and to make them easier to care for.

—————————————-

Don’t wait for dry weather to learn about an easy and better (for you and plants) way to water. On June 24, 1-4:30 pm, I’ll be holding DRIP IRRIGATION WORKSHOP at the garden of Margaret Roach in Copake Falls, NY. Learn how to design a system, and participate in a hands-on installation. For more information and registration, www.leereich.com/workshops.

AWESOME BLOSSOMS & RATIONALITY

/1 Comment/in Flowers, Gardening, Planning, Vegetables/by Lee Reich

Wow!!

With blossoms spent on forsythias, lilacs, fruit trees, and clove currants, spring’s flamboyant flower show had subsided – or so I thought. Pulling into my driveway, I was pleasantly startled by the profusion of orchid-like blossoms on the Chinese yellowhorn tree (Xanthoceras sorbifolium). And I again let out an audible “Wow” as I stepped onto my terrace, when three fat, red blossoms, each the size of a dinner plate, stared back at me from my tree peony.

Both plants originate in Asia. Both plants are easy to grow. Both plants have an unfortunate short bloom period, more or less depending on the weather. Fortunately, both plants also are attractive, though more sedately, even after their blossoms fade.

The tree peonies have such a weird growth habit. I had read that they were very slow to grow so was quite pleased, years ago, when each of the branches on my new plant extended its reach more than a foot by the end of its first growing season. Tree peony is a small shrub; at that rate mine would be full size within a very few years. Or so I imagined.

The tree peony still grows that much every year. But every year many stems also die back about a foot, more following cold winters. No matter, though, because every May giant silky, red flowers unfold from the remaining fat buds along the stem.

I originally planted Chinese yellowhorn not for its flowers but for the fruits that follow the flowers. Each fruit is a dry capsule that later in summer starts to split open to reveal within a clutch of shiny, brown, macadamia-sized nuts. Yellowhorn frequently makes it onto permaculture plant lists, with the edible nuts billed as having macadamia-like flavor also. Not true. I’ve tried them raw and roasted. Roasting does change the flavor, but raw or roasted, the flavor is bad.

Still, those blossoms make yellowhorn well worth growing. And after the blossoms fade, this small tree is adorned with shiny, lacy leaves. Much like the tree peony, yellowhorn grows many new stems each year, and many of the stems die back, not necessarily from winter cold but because they’re seemingly deciduous. I tidied the tree up last week by pruning off all the dead stems.

Out With You-All

Today, May 25th, with temperatures around 90 degrees F., I may not be able to restrain myself. It’s hard to imagine that temperatures could still plummet below freezing at least one night sometime in the next week or so. I’ve already ignored that “should” and a few days ago moved houseplants outdoors.

Why the rush? First of all, houseplants enjoy growing outdoors more than growing indoors. Outside, breezes rustling leaves and stems make for stronger, stockier growth and rain showering the leaves washes off a winter’s accumulation of dirt and grime.

After a winter indoors, the plants do need to acclimate to these conditions, which is why they start their outdoor vacation on the terrace on the north side of the house, which blocks wind and, for part of the day, sunlight.

I also urged the plants outdoors because populations of aphid and scale insects were outgrowing the appetites of the ladybugs crawling up and down the stems. Outside, natural predators keep pests in check and, if necessary, I can spritz the plants down to knock off pests and spray soap or summer oil to kill them without worrying about getting spray or oil on windows, walls, or furniture.

The Rush On Sweet Corn

Even tender seeds, such as corn, squash , and beans, can be sown now. The earth has warmed enough for decent germination, and by the time the plants are up, warm weather will have settled in for the season.

Tomorrow I plant sweet corn. Kinky as it sounds, I’m anxious to sink my teeth into a freshly picked ear.

Upcoming Workshop

June 24, 1-4:30 pm, DRIP IRRIGATION WORKSHOP at the garden of Margaret Roach in Copake Falls, NY. Don’t wait for dry weather to learn about this easy and better (for you and plants) way to water, including participation in hands-on installation. For more information and registration, www.leereich.com/workshops.