It Ain’t Over ‘Til It’s Over, and Pears

/0 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Planning, Vegetables/by Lee ReichWhoosh!

Whew! How quickly this growing season seems to have scooted by. I am putting the last plants of the season into the vegetable garden today. These were transplants of Shuko and Prize Choy bok choy, and Blue napa cabbage. I’m eyeing some lettuce transplants, and if I decide that they’re sufficiently large to transplant, they’ll share a bed with the cabbages.

Reconsidering, the end of the gardening season isn’t really drawing nigh. The cabbages won’t be large enough to make a real contribution to a stir fry or a batch of kim chi for at least another month. And then, with cool weather and shorter days slowing growth, the plants will just sit there in the garden, doing fine, patiently awaiting harvest.

Other plants awaiting harvest into autumn from plantings over the past few weeks are Hakurei turnips, crunchy, sweet, and spicy fresh in salads, daikon and Watermelon radishes, for salads or kim chi, and, also for salads, lettuce, spinach, arugula, and mustard greens. The last salad stuff will be endive, sown back in early July, and transplanted in early August in a bed previously home to the first planting of bush beans.

The season’s various plantings mesh together nicely. Those bok choy and napa cabbages went into a bed just cleared from the first planting of sweet corn. The bed previously planted with of lettuce, arugula, and spinach seed followed on the heels of onions sown indoors in February, transplanted into the bed in May, and harvested a few weeks ago.

A Whole New Garden, Now

In addition to good timing, the autumn garden — which is like having a whole other garden, except it’s in the same place as the summer garden — demands good soil. That soil has to support this whole other wave of plants.

Through summer, I looked upon any weeds I encountered as potential factories for making more weeds, via spreading seeds and/or roots. Left alone, that weed and its progeny would rob food and water meant for my cabbages and lettuces, and shade my plants into submission.

With that in mind, when I cleared the beds of spent corn or bean plants, I pulled out every weed in addition to the spent vegetable plants. I tried to get roots and all for each weed, which isn’t that difficult if you keep up weeding all summer.

After clearing a bed of weeds and vegetable plants, down went a carpet of compost.  A one to two inches deep layer smothers most weeds sprouting from seeds as well as provides nourishment for multiple waves of vegetable plants — for a whole year! (Also provides food and habitat for beneficial soil organisms, protects the surface from washing, and increases the soil’s ability to hold on to both air and moisture.)

A one to two inches deep layer smothers most weeds sprouting from seeds as well as provides nourishment for multiple waves of vegetable plants — for a whole year! (Also provides food and habitat for beneficial soil organisms, protects the surface from washing, and increases the soil’s ability to hold on to both air and moisture.)

So the season hasn’t scooted by; the autumn season is just beginning. There’s still some room for reflecting on the season up to this point. Most notable has been this year’s pear crop.

Pears: Easy To Grow, Hard To Harvest (Correctly)

Among the common tree fruits, pears are the easiest to grow. They’re a bit slow to come into production but are often free of significant pest problems. They’re also pretty trees, all season long, especially the Asian pears.

It’s not all smooth sailing from planting to flowering to harvest to eating for European pears, which includes Bartlett, Bosc, Anjou, and other pears with which most people are most familiar. The problem is knowing when to harvest them. Pears ripen from the inside out, so need to be harvested when mature (whenever that is), then ripened in a (preferably cool) room indoors. Left hanging on the tree too long, and the fruit tastes sleepy, at best, or has turned mushy; harvested too soon and the fruit never loses a grassy flavor. (Asian pears are easy to harvest. When they taste good right off the tree, they’re ripe and ready.)

Frederick Clapp pear tree

Appearance of the fruit, calendar date, and ease of separation from the stem when lifted with a twist are all indicators of ripeness. I’m finding that few fruits dropping from a tree are a good sign that it’s time, or almost time, to harvest.

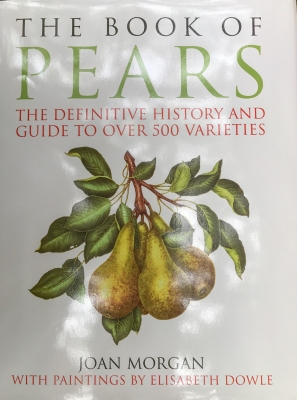

Pears, A Book

As luck would have it, a beautiful new book, The Book of Pears, by Joan Morgan, arrived in the mail just as pear harvest was beginning (with the variety of Harrow Delight). Replete with old and new illustrations depicting the history of pear cultivation, a large portion of the book offers intimate descriptions and history of many varieties. Beurrée d’Amanlis, for instance, which I grow, originated in a small village in Brittany, but became popular after 1826, when Louis Noisette, a Paris nurseryman, received some fruit from his son, director of the Nantes Botanic Garden.

The book devotes a little space to growing and cooking the fruit. I, of course, immediately looked to see what Ms. Morgan has to say about harvest: “ . . . the next challenge is when to harvest the crop . . . Once they begin to drop from the tree it is time to harvest . . . Experience with your own trees will tell you when to pick.” How true. I’ve grown the variety Magness longest, and usually can pick them to ripen off the tree to perfection. And perfection for Magness means biting into one of the best tasting of all pears.

The Destroyer To The Rescue

/5 Comments/in Flowers, Fruit, Gardening, Planning/by Lee ReichPredatory Helpers

Some of the figs — the varieties Rabbi Samuel, Brown Turkey, and San Piero — started ripening last week. With their ripening, I am now in a position to claim victory over the mealybugs that have invaded my greenhouse fig-dom for the past few years.

Mealybugs look, unassumingly, like tiny tufts of white cotton, but beneath their benign exteriors are hungry insect. They injects their needle-like probiscis into stems, fruits, and leaves, and suck life from the plants, or at least, weaken the plants and make the fruits hardly edible.

Mealybugs look, unassumingly, like tiny tufts of white cotton, but beneath their benign exteriors are hungry insect. They injects their needle-like probiscis into stems, fruits, and leaves, and suck life from the plants, or at least, weaken the plants and make the fruits hardly edible.

Over the years I’ve battled the mealybugs at close quarters. I’ve scrubbed down the dormant plants with a tooth brush dipped in alcohol (after the plants were pruned heavily for winter). I’ve tried repeated sprays with horticultural oil. I put sticky bands around the trunks to slow traffic of ants, which “farm” the mealybugs. And I’ve rubbed them to death with my fingers when I came across them on the stems. All to no avail. The mealybugs always made serious inroads into the harvest.

Mealybugs finally have been quelled this season thanks to another insect, the aptly named “mealybug destroyer” (Cryptolaemus montrouzieri), available from www.insectary.com. To soldier along with the mealybug destroyer, I also ordered some green lacewing (Chrysoperla rufilabris) eggs. Besides attacking the mealybugs, the lacewings prey on aphids, seizing the aphids in their large jaws, injecting a paralyzing venom into them, and then sucking out their body fluids. With good reason, lacewings are also called aphid lions.

Mealybug destroyer

I ordered the first batch of predators in early summer. After recently noticing a buildup of mealybugs again, I ordered another batch. The mealybug destroyer and aphid lion populations may have plummeted after they ate all the bad guys, or they may have found their way to greener pastures via the many openings in the greenhouse.

The smallest amount of either pest that could be purchased could have policed a greenhouse much larger than mine, so the predators were relatively expensive: about $80 per shipment, with shipping. Still, I estimate the potential ripening of about 160 figs, which brings their cost to $1 per fig. Not bad for a dead ripe, juicy, ambrosial fruit that, with each bite, transports me back thousands of years to the Fertile Crescent, where figs originated.

Help From The Queen

A visitor to my greenhouse might have thought it looked weedy this summer. Tall flower stalks of Queen Anne’s lace grew with abandon, cilantro flowered and then their seed heads flopped down willy nilly, lettuce grew bitter as the plants bolted, and mustard greens shot up stalks capped with yellow flowers. There was reason for this wild wantonness.

The purpose of all these flowers was to encourage the adult mealybug destroyers and aphid lions to stick around. Flowers of plants in the Carrot Family, such as Queen Ann’s Lace and cilantro, the Daisy Family, such as lettuce, and the Mustard Family, such as, of course, mustard, provide nectar and pollen that the predators enjoy. The Carrot Family Helps Out

The Carrot Family Helps Out

I also encouraged beneficial insects outdoors, in my vegetable gardens, by growing or, at least, letting grow, some of these same plants.

Add to that list dill, another member of the Carrot Family, which I always let flower and set seed in the garden. Those seeds become next year’s dill plants with no extra effort on my part except to weed out excess self-sown seedlings.

For some reason, dill did not self-seed in the garden the past two years, so this year I bought and planted seed. “Planted” might be too specialized a term for what I did. In fact, I just tore open the packet of seeds, poured them into my hand, and waved my hand as I let the seeds fly. Like magic, seeds sprouted a few weeks later.

This season’s dill not only encouraged beneficial insects and provided some ferny leaves and seed heads for flavoring, but also provided beauty. The variety was ‘Fernleaf,’ which grows dwarf, compact plants that also are slower to make flower heads. Perhaps it was the compactness of the flat heads of greenish yellow flowers or the denser backdrop of green leaves, but the plants captured my attention every time I walked by them. Still do, because they’re still blooming.

Queen Anne’s Lace also appeared in my garden with no extra effort on my part. Not only from self-seeding, as a weed. But also from an occasional rogue carrot seed from those I planted. Queen Anne’s Lace and carrot are the same genus and species, carrots having been selected and bred to make fatter, juicier, tastier, and orange-er (or, these days, purple-er) roots.

Here, at least, this season was particularly welcoming of QueenAnne’s Lace. The meadow next to the vegetable gardens has been dotted white with an abundance of their flowering heads.

The Bad and the Good

/6 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening/by Lee ReichWinecaps, Not For Me

My successes with growing shiitake mushrooms emboldened me, this past spring, to venture further afield, to wine cap mushrooms (Stropharia rugosoannulata). After all, it’s been billed as “prized, delicious” and “edible when young.”

Their quick production also prompted me to give them a try. As a matter of fact, my spring “planting” started bearing a couple of weeks ago. A bed can also be refreshed or a new bed can be inoculated from an old bed for repeat performances.

Let’s go back to spring, to my planting. Wine caps grow very well in wood chip mulch, something that’s aplenty on my farmden. My berry bushes are mulched, my pear trees are mulched, as are the paths in my vegetable gardens. Why not do double duty with those mulches?

A few years ago, I attempted just that, laying a thick mulch of chips atop my asparagus bed in spring. Two problems: The thick mulch almost killed the plants, and the weather was very dry for weeks on end. Mushrooms need moisture.

This past spring, I pulled back twigs and other debris from a patch of ground beneath a Norway spruce tree and laid down a few inches of hardwood chip mulch. After sprinkling the purchased spawn over the mulch, I topped everything with another inch or two of, this time, wood shavings.

For this spring’s planting, I also decided to water, so set up a sprinkler. Rain fell pretty consistently all season long, obviating the need for further watering.

The tasting: To me, the mushrooms were tasteless. Sure, I could have sautéed them with butter and garlic; then they would have tasted like butter and garlic. (Disclaimer: Your results may differ from mine.)

My taste for wine cap mushrooms went down another notch when I more recently read a caution to eat them moderately and not more than two days in a row. My yard abounds with plenty of other good tasting, healthful food, so I’ll pass on the wine caps.

Seaberries For Me

On to more tasty items. Seaberries (Hippophae rhamnoides). The harvest is in, the first harvest from my 2013 planting. I wanted them for juice and, on the recommendation of seaberry expert Jim Gilbert of www.onegreenworld.com, planted Titan, Leikora, and Orange Energy.

Seaberry plants are either male or female. Only female plants bear fruit; to do so, they need pollen from a nearby male, which I also planted. One male can sire up to 8 females.

Seaberry, Titan

In addition to yielding very healthful berries, seaberries further earn their keep as landscape plants. (I’ve seen them planted as ornamentals in New York City’s Battery Park.) The bush’s thin, olive green leaves are the perfect backdrop for the bright orange berries, clustered thickly right along the stems.

And there’s the rub. Long, sharp thorns also cluster along the stems, making harvest a potentially painful proposition.

I used the method Jim recommended for harvest, and that is to cut stems heavily laden with berries into 6 inch long pieces, put them into a covered plastic tub, and then freeze them. The frozen berries came off the stems when the tub was shaken vigorously. All I had to do then was to pick out the stems, and then winnow the leaves from the fruit in front of a fan.

The berries are now back in the freezer, to be made into juice at my leisure. That’ll involve cooking them in a little water, mashing them with a potato masher, and then straining. My previous planting yielded a delicious juice once diluted with 1/8 part water and sweetened with 1/8 part maple syrup or honey.

This season’s juice should be even better because the berries taste better than the previous varieties I planted. Especially good — even straight from the bush — in the new planting is the variety Titan. Seaberry generally tastes, to me, like very rich orange juice with the addition of pineapple or passionfruit. Titan has more of a tangerine-y flavor.

Permaculture-esque

Wine cap mushrooms and seaberries are both plants beloved by permaculturalists. The mushrooms for the little care they need, and their use of mulched ground. The seaberries, also for their low maintenance, their beauty, and their enrichment of the soil with nitrogen.

Seaberry bush

My seaberries are in a permaculturalesque planting, along with elderberry, highbush cranberry, nannyberry viburnum, rugose rose, Korean pine, and aronia. They’re all easy to care for. They’re all very ornamental. The only ones that taste good or yield anything are the seaberry and the rugosa roses.