(Micro)climate Change

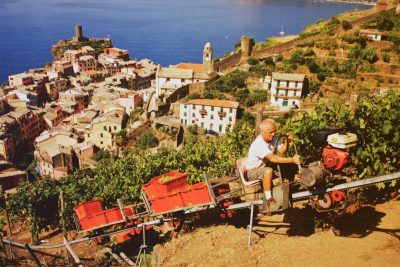

/3 Comments/in Fruit, Gardening, Planning/by Lee ReichAs the train rolled southbound along the east bank of the Hudson River, I took in the varied landscapes along the opposite west bank. Spilling down the slope to the river on that bank at one point was what appeared, from a distance, to be a vineyard. I was envious.

(I never could understand why the region here is called the Hudson Valley. Along much of the Hudson, the land rises steeply right up from river’s edge. Where’s the valley?)

I wasn’t envious of the riverfront site of the vineyard property. I wasn’t even envious of having a whole vineyard of grapes. (I cultivate about a dozen vines.)

What I did envy was the microclimate of the site. Microclimates are pockets of air and soil that are colder, warmer, more or less windy, even more or less humid than the general climate, due to such influences as slopes, walls, and pavement.

The vineyard was not that far from my home, but the microclimate was worlds apart. Every parcel of land, from a forty-acre farm field to a quarter acre lot, will have some microclimates, and siting plants with this in mind can spell the difference between whether or not they thrive or even survive.  I’m banking, for instance, on the slightly warmer temperatures near the wall of my house to get my stewartia tree, which is borderline hardy here, through our winters. (It has.) And I expect spring to arrive early each year, with a colorful blaze of tulips, in the bed pressed up against the south side of my house. Proximity to paving also warms things up a bit.

I’m banking, for instance, on the slightly warmer temperatures near the wall of my house to get my stewartia tree, which is borderline hardy here, through our winters. (It has.) And I expect spring to arrive early each year, with a colorful blaze of tulips, in the bed pressed up against the south side of my house. Proximity to paving also warms things up a bit.

Microclimate for cold, microclimate for warmth

Microclimate isn’t always about trying to keep a plant warmer in winter, or speeding up growth in spring. It’s also useful for keeping plants cooler. By training my hardy kiwifruit (Actinidia spp.) vines right up against the shaded, north sides of their hefty supports, I keep the sun off their trunks in winter and avoid the splitting that occurs when trunks are warmed during winter days, then precipitously cooled as the winter sun drops below the horizon.  By planting the coveted blue poppy in a bed on the east side of my house, I hoped to give the plant the summer coolness that it demands. (That east bed was still too sultry; the plants collapsed, dead.)

By planting the coveted blue poppy in a bed on the east side of my house, I hoped to give the plant the summer coolness that it demands. (That east bed was still too sultry; the plants collapsed, dead.)

Microclimates are important when growing fruit plants that blossom early in the season because frozen blossoms do not go on to become fruits. Early season bloomers need microclimates that are slow to warm up.

South facing slopes stare full face at the sun, so these slopes warm up early in spring and are warmer in both summer and winter. Therefore, a south facing slope—even if the grade is only slight—can be used to hasten fruit ripening on a plant like persimmon, which blooms late but needs a long season when grown near its northern limits.

Right after I push soil over the first seeds of sweet corn that I plant, I firm it over that hole with my foot at an angle to make a south-facing depression in the ground. That mini-slope will warm up just a wee bit sooner than flat ground.

The sun glances off north slopes, delaying their warming in spring and keeping them cooler in summer. Such a microclimate is ideal for an early blooming fruit tree like apricot or peach, and for plants, such as sweet peas, that enjoy cool summer weather. Likewise ideal for such plants is near the north side of a building, where shade remains through winter and the early part of the growing season.

If a slope actually has some elevation to it, the air is going to cool by one degree Fahrenheit every three-hundred feet going up the slope. If I had sloping ground, which I don’t, and sought a cooler location for planting, I’d avoid planting at the very top of the slope, though, because the upper reaches are usually windy.

A cold spot, here

Ideal vineyard site, from plant perspective, in Germany

Counterintuitively, the very bottom of a slope will also be a cooler microclimate. On nights when the sky is clear, with no clouds or leafy trees to block re-radiation of the sun’s heat from the ground back to the heavens, the air at ground level cools. An “inversion” occurs, with warmer air higher up. The cold air, which is denser than warm air, flows downhill to settle into depressions, just as a liquid flows downhill. A low point would be the worst possible location for planting strawberries, which grow near ground level and whose early blossoms are threatened by late frosts in spring. Any dense fence or shrubbery on a slope stops the downward flow of cold air, which will pool, just as dammed water would, near the upper side of the barrier.

Among the fruits I grow are apples, peaches, plums, and pears, all of which tend to bloom early. My site, unfortunately, is just about the worst possible site for growing these fruits.  The cold air that settles here on clear spring nights increases the likelihood of late frosts and also causes moisture to condense on the plants, leaving them more susceptible to disease. Hence my envy for that sloping vineyard site.

The cold air that settles here on clear spring nights increases the likelihood of late frosts and also causes moisture to condense on the plants, leaving them more susceptible to disease. Hence my envy for that sloping vineyard site.

Check out my new book, The Ever Curious Gardener, for more on microclimate!!

Doing Good with Saw and Lopper

/4 Comments/in Flowers, Fruit, Gardening, Pruning/by Lee ReichFruitful Pruning

To begin, I gave the bush in front of me a once over, eyeing it from top to bottom and assuring it that the next few minutes would be all to its good. It was time for my blueberries’ annual pruning, the goals of which were to keep them youthful (the stems, at least), fecund, and healthy.

Blueberries galore

I peered in at the base of the plant, eyeing now the thickest stems. Blueberry bushes bear best on stems up to 6 years old, so the next move was to lop or saw any of these stems — usually only 3 or 4 of them, more on a neglected plant — as low as possible.

Sammy & me, pruning blueberries

To keep track of the ages of individual stems, I mark off the age of them each year with a Sharpie. Just kidding! The thickest ones are the oldest ones, and 6-year-old stems are generally an inch or more in diameter on healthy bushes.

Removing those stems that are over the hill frees up space for younger stems to develop. Each year blueberry bushes send up new sprouts from ground level, usually a few too many of them. They need to be thinned out so they don’t crowd each other as they age. I leave a half dozen or so of the most vigorous new sprouts, lopping all others to the ground.

That’s pretty much all there is to pruning a blueberry bush. With the very oldest and some of the very youngest stems cut to the ground, the bulk of pruning the bush is finished.

Blueberry bush, before & after pruning

I’ll also snip off any dead stems, remove a branch here and there where they are congested, and shorten any stems that will arch to the ground when laden with fruit.

That’s it. Finished, except to step back and admire my handiwork.

And Now, For Other Shrubs

The same pruning done on blueberry could, in essence, be applied to lilac, forsythia, mockorange, hydrangea, and any other informal shrub. This technique is known as rejuvenation pruning because, over time, the above ground portion of the shrub is annually rejuvenated. In the case of blueberry, the roots live unfettered year after year but the bush never sports stems more than 6 years old. A perennially youthful blueberry bush can go on like this, bearing well, for decades like this.

forsythia, mockorange, hydrangea, and any other informal shrub. This technique is known as rejuvenation pruning because, over time, the above ground portion of the shrub is annually rejuvenated. In the case of blueberry, the roots live unfettered year after year but the bush never sports stems more than 6 years old. A perennially youthful blueberry bush can go on like this, bearing well, for decades like this.

Not all shrubs perform best on stems up to 6 years old. Some, such as kerria, snowberry, rambling roses, and summer-bearing raspberries perform best on 1-year-old stems. So every year those 1-year-old stems are lopped to the ground and the youngest stems are thinned out.

Some shrubs, such as butterfly bush, everbearing raspberries, and red twigged dogwood, perform best on new stems. In this case, the whole plant gets lopped to ground level each year. (Everbearing raspberries actually bear on both new stems and on 1-year-old stems, so could be pruned as in the previous paragraph. That takes more time but does yield a midsummer crop on the 1-year-old stems and a late summer and fall crop on the new stems.)

At the other end of the spectrum in shrub pruning are witch hazel, tree peony , rose-of-sharon, climbing roses, and flowering quince. These shrubs are among those that perform well year after year on the same old, and always growing older, stems. They also grow few or no suckers each year. The upshot is that thesis shrubs are the easiest to prune: Don’t.

, rose-of-sharon, climbing roses, and flowering quince. These shrubs are among those that perform well year after year on the same old, and always growing older, stems. They also grow few or no suckers each year. The upshot is that thesis shrubs are the easiest to prune: Don’t.

I detail the ages of stems that are “keepers” for every shrub, plus other details in pruning all kinds of plants, in my book The Pruning Book.

Getting Formal

All this pruning refers to informal shrubs. For formal shrubs, such as the privet hedge near one edge of my yard, I put aside the lopper, pruning shears, and pruning saw, and get out the hedge trimmer. Shearing all the youngest twigs, working, this time, higher in the bushes rather than down near ground level, elicits repeated branching which results in dense growth.

To keep this formal hedge clothed from head to toe in leaves, I keep the row of plants narrower towards their upper portions. This lets sunlight beam down on the shrubs from top to bottom.