ALL ABOUT ONIONS

An Ode

Onions, how do I plant thee? Let me count the ways. I plant thee just once for years of harvests if thou are the perennial potato or Egyptian onion. If thou are the pungent, but long-keeping, American-type onion, I sow thy seeds in the garden in the spring. And if I were to choose like most gardeners, I would plant thee in spring as those small bulbs called onion “sets.” (Apologies to E.B. Browning)

New Old Ways with Onions

Early March brings us to yet another way of growing onions: sowing the seeds indoors in midwinter. This was the “New Onion Culture” of a hundred and fifty years ago, and, according to a writer of the day, “by it the American grower is enabled to produce bulbs in every way the equal of those large sweet onions which are imported from Spain and other foreign countries.” This is the way to grow the so-called European-type onions.

Walking onions

What’s wrong with growing perennial onions, American-type onions, and onion sets? Neither perennial nor American-type onions have the sweet flavor of the famous Vidalia onion, a European type. And onions for sets are generally limited only to the two varieties marketed, Stuttgart and Ebenezer, whose important quality is that they make good sets. A few seeds companies sell sets of a better variety, Forum. In addition to variety, quality of sets is important: too large and they become useless as they send up seedstalks.

The New Onion Culture is a way to grow the large, sweet, mild European onions, such as Sweet Spanish.

The “Method” is as follows: About 10 weeks before the last hard freeze, fill a seed flat with potting soil and use a plant marker to make furrows 1/2-inch deep and one inch apart. Drop about seven seeds per inch into the furrows and then cover the seeds with soil. Fresh seed, less than a year old is best. Water the flat, then keep it moist and warm and covered with of pane of glass. The onions should sprout in a week or two.

Once the onions sprout, remove the plastic or glass and give the seedlings plenty of light. Put the flat either within a few inches of fluorescent lights, on a very sunny windowsill, or in a greenhouse. Each time the seedlings grow to six inches height, clip them back to four inches. The trimmings, incidentally, are very tasty. This indoor stage of plant growing can be bypassed by purchasing onion transplants (not sets), which are sold mail-order in bundles of twenty-five.

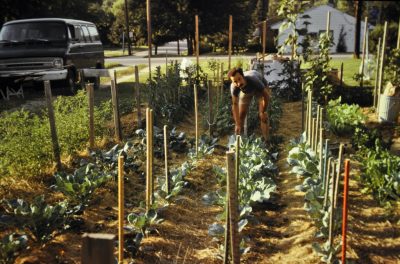

Get ready for transplanting a few weeks before the predicted last freeze date. Choose a garden spot where the soil is weed-free, well-drained, and bathed in sunlight. Onions demand high fertility; my plants go into a bed that was dressed with an inch depth of compost last fall. Give the onion seedlings their final haircut, tease their roots apart, then set them in a furrow, or individual holes dibbled with a 3/4-inch dowel. Plant seedlings two to four inches apart, two inches if you want small bulbs, four inches if you want big bulbs.

This may sound like a lot of trouble to grow onions. But for me, midwinter onion sowing inaugurates the new gardening season. The onion is an apt inaugural candidate; it responds to “high culture” starting with careful sowing in fertile soil and moving on to good weed control, timely watering, and, after harvest, correct curing after harvest.

Besides providing this midwinter ritual, onions raised according to the New Onion Culture do have superb flavor.

(The above was adapted from my book A Northeast Gardener’s Year.)

And Still Newer Ways

And now for the “Newer Onion Culture”: American-type onions have the advantage of being better for long-term storage, and newer varieties also have very good flavor. My current favorites are Copra, Patterson, and New York Early. They also are “long day” onions, setting bulbs when the sun shines for 15 to 16 hours daily. “Short day” varieties, which are adapted to the South, would bulb up too soon around here, producing puny bulbs.

There’s more to the “Newer Onion Culture.” A couple of years ago, a local farmer, Jay, of Four Winds Farm, told me he gets good results by just planting seeds in furrows right out in the field.

And even more. Instead of planting 7 seeds per inch indoors in furrows in early March, sow them in flats of plastic “cells” with 4 seeds per cell (each cell is about an inch square).  When transplanting out in the garden, plant each cell with its seedlings intact, spacing them further apart than you would with individual transplants so their roots get adequate water and nutrition. As vegetable growing maven Eliot Coleman wrote in Four-Season Harvest, “the onions growing together push each other aside gently.”

When transplanting out in the garden, plant each cell with its seedlings intact, spacing them further apart than you would with individual transplants so their roots get adequate water and nutrition. As vegetable growing maven Eliot Coleman wrote in Four-Season Harvest, “the onions growing together push each other aside gently.”

Back to my original query: “Onions, how do I plant thee.” Many ways. I’ll do four out of the six ways this season.

In the case of plants like petunia, chrysanthemum, rhododendron, and fuchsia, at least part of the botanical name is the same as the common name in English. In some cases, using the botanical name might be the only way I could be assured of getting the plant I really want. If I wanted to plant bluebells, Hyacinthoides, and searched and asked for it by its common name, I could end with plants in the Mertensia, Muscari, Campanula, or Eustoma genus.

In the case of plants like petunia, chrysanthemum, rhododendron, and fuchsia, at least part of the botanical name is the same as the common name in English. In some cases, using the botanical name might be the only way I could be assured of getting the plant I really want. If I wanted to plant bluebells, Hyacinthoides, and searched and asked for it by its common name, I could end with plants in the Mertensia, Muscari, Campanula, or Eustoma genus.

It just so happens that the most flavorful fruit and vegetable varieties are ones that have been around a long time. Yields may not be heavy, but these varieties are rich in flavor. (And perhaps nutrients. Anyway,

It just so happens that the most flavorful fruit and vegetable varieties are ones that have been around a long time. Yields may not be heavy, but these varieties are rich in flavor. (And perhaps nutrients. Anyway,